![]()

1

The Story So Far . . .

AT THE AGE OF ELEVEN WHEN I WAS ATTENDING SIXTH grade and living in Gagret, a small village in northern India, I was stricken with mumps and typhoid and became deaf overnight. I thought I had died and gone to hell. I had never met a deaf person in my short life and not being able to hear made me feel less than human. The school I was attending seemed to agree with me on this demotion and discharged me. The idea of a deaf person attending school just did not enter in anyone’s mind. That included me. Fortunately or unfortunately, no one in my family and circle of acquaintances knew about schools for the deaf. So there I was—a young deaf boy with no future and less hope.

That was in 1952. The idea of spending the whole life as a behra (Urdu equivalent of “dummy”) for the rest of life didn’t seem very palatable. My father, whom we all called Babuji, listened to all kind of “expert” advice and decided that deafness was a sickness since it was tied to typhoid and mumps. Like other sicknesses, it should be able to be cured. He tried all kind of remedies—regular Western doctors, ayurvedic (traditional Indian) medicine, hakeems practicing Greek medicine and, most of all, faith healers of all varieties. All of them gave me drugs in various shapes, sizes, and colors as well as cure-all ashes blessed by “holy men” that are found in every village. Needless to say, none of these worked, and, as I write this book about sixty years later, I am still deaf.

Seeing that no cures were working and I couldn’t go to school, Babuji suggested that I should start working on our farm along with the servants. No one in our family had ever worked on the farm. We were landlords. My deafness had helped me win this “privilege.” I started out as a cattle herder that required me to drive cattle a few miles away to one or the other pastures and watch over them all day long. I also had to cut grass, milk water buffaloes, and cows; collect and carry cow dung; and

carry water from the well for the family. Later, I was promoted to plowing the fields behind a pair of oxen and weeding and reaping wheat, corn, rice, and sugarcane.

My nine years working on the farm were pure hell. I hated every minute of it but managed to survive by my being a hopeless and unashamed optimist. I kept hoping that I would start my journey to become a successful person. What “success” entailed was never clear to me.

However, none of this stopped my education. My parents encouraged me to study on my own. Each year, as my elder brother Sham, who was a year ahead of me in school, moved on to the next class, I inherited his used textbooks. I spent every free minute with these textbooks. Reading came naturally to me and my problem was being unable to stop reading. I would finish the textbooks assigned for the whole year in a week. History and other subjects that depended on reading were also a cinch. For mathematics, I had to depend on sporadic tutoring by my brothers Sham and Narain. The big problem was learning English. In India at that time, instruction in English began during the fifth grade. I had the fortune of learning the alphabet and some basic English sentences such as “Mohan puts on a shirt.” However, I wanted to learn English and learn it well as it was the ticket to big things.

I wrote down each grammatical construction that I could think of in Hindi and had Narain, my eldest brother, write down English equivalents. These were simple sentences like “I go,” “I am going,” “I have been going,” and so forth. I started to make English sentences using Hindi language as a base. I would look at whatever I saw and try to describe it in English in my head. “That ox blue is” and correct it to “that ox is blue” after consulting my chart. This helped me get a good grasp of English grammar. Reading English books (mostly cowboy novels) using a dogeared dictionary helped me build vocabulary. I read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice in several months. All of these haphazard approaches to education helped me improve my English and learn Sanskrit, mathematics, and other subjects. Seeing my progress, Babuji suggested I should take the high school examination. In 1957 I was a high school graduate, still herding cattle and plowing fields. My real education was mostly from reading all kind of books, any books that I could find. Since there was no library around, I had to walk as far as thirty miles to buy books from a junk shop.

I hoped that my education would be my ticket out of Gagret. However,

I also did think about becoming a sadhu (holy man), a cleaner, or an assistant to some truck driver, as farming was not exactly my cup of tea.

The “ship” showed up in 1961 when Narain, my elder brother who lived in Delhi, learned about a photography school for the deaf being opened there. I jumped at the chance, and I packed a small bag and rode the train to Delhi the same day. After a stint working in a printing press, I joined the Photography Institute for the Deaf. This is where I met other deaf people for the first time and saw them using signs. I could not believe two people could communicate by moving their hands around. The two deaf guys refused to teach me signs as if it was a national secret. After some initial frustrations, I was able to make friends with my classmates. Within a week, I was signing fairly well. A whole new world opened for me.

During the next two years, I learned photography and sign language and also learned about deaf people, though not necessarily in that order. I got immersed within the Deaf community slowly as I became a fluent signer. After I earned my diploma in photography in two years, I started to teach in the same school. At the same time, I became a leader both in the Deaf and Dumb Association of Delhi and the All India Federation of the Deaf. More than that, I learned there was life after deafness and it was a good one.

Then another opportunity knocked. On encouragement from Narain, I applied for a government job as a technical photographer. This was a long shot and I was hesitant. However, I managed to pass the technical part of the examination with high marks, got the interview, and got the job. Getting a job in a stiff competition with about seventy hearing people helped me become a “successful” deaf person in the Delhi area. I had it made, so I thought. The next three years were great as I worked in a nice job, had a huge network of friends—both deaf and hearing—and rose as a leader among deaf people in Delhi and India.

The next logical step, of course, was getting married. Following the Indian tradition, I was betrothed by an arrangement made by relatives. It was decided that I would get married in a couple of years and then settle down in Delhi. However, something else was in store for me.

A deaf American lady, Hester Bennet, wrote to the office of the All India Federation of the Deaf asking for help in visiting Delhi in 1966. Since I was one of the few people fluent in English, Mr. B. G. Nigam, the general secretary, asked me to show the deaf lady around. For two days, very proudly, I took her around Delhi showing her the historical sites.

She did not know Indian signs and I did not know any American. So we communicated using pen and paper and some gestures for two days. On the second day, she asked me why I did not attend Gallaudet College. I could not believe there was a college for the deaf. The very next day, I went ahead and applied for admission.

In 1967, two important things happened in my life. I got married and moved to the United States to attend college.

My marriage to Nirmala (Nikki) was arranged by my aunt, Babuji’s younger sister. Arranged marriage was the norm in India at that time. Unlike American couples, we had not fallen in love. We had not even dated. Actually, we had not even met each other. We both married strangers in February 1967 following the traditional Hindu ceremony, which lasted three days.

The saga of my coming to the United States after my admission to Gallaudet College is long and arduous. I was accepted and granted a full scholarship that covered tuition and room and board. However, I had to pay for books and unit fees, which amounted to $250. Due to stringent foreign exchange rules at that time, I had to have this amount in dollars and not in rupees. I wrote to Hester Bennet and she contacted Byron B. Burnes, then president of the National Association of the Deaf. Mr. Burnes wrote me a letter offering that amount and explained that he had deposited a check for $250 with Mr. Philips, the dean of students at Gallaudet. I thought the problem was resolved. However, this did not satisfy the Indian foreign ministry bureaucrats. This was a personal letter and they wanted an official letter from Gallaudet College. A letter from India to the United States took two weeks to arrive and sometimes more. Each exchange of letter between me and Mr. Burnes or Mr. Philips took almost a month. However, it was much faster compared to the Indian bureaucracy. It took my brother Narain and me a whole month of pounding doors outside various offices to finally get the needed documents that would allow me to apply to the U.S. embassy for a student visa.

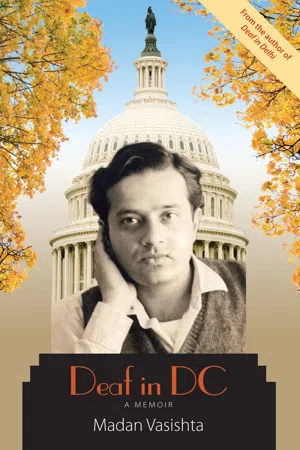

The story here begins with my arrival in Washington, DC, on September 14, 1967.

![]()

2

Arrival in America

AIRPLANES, TO ME WHILE HERDING CATTLE IN GAGRET, looked like birds, a bit larger than a crow and the same size as a vulture. Later, when living in Delhi, I had the opportunity to see some of them at the airport. They were larger, much larger. I saw scores of people disappear into the belly of the “bird.” However, the closest I had gotten to an airplane was the visitor’s gallery at the airport. I longed for the moment when I would also ride an airplane. Now, I was actually flying in a plane. I hoped the plane would fly over Gagret so that I could look down to see how small the cows looked.

Sitting on the airplane felt funny. There was no sign of the heat or humidity that was suffocating the airport outside. The faint aroma of hot cooked food wafting from the galley reminded me that I was hungry. The combination of many emotions—excitement, worry, sadness, fear—had pushed the basic human need, hunger, to the background. I wished the plane would fly and those pretty air hostesses dressed in colorful silk saris would serve food.

No one had bothered to tell me if the plane was going directly to London or would stop on its way. I had not asked, either. I sat in the cramped seat next to a young lady who tried to talk to me and, on finding I was deaf, wrote, “Do you know if we are flying over Amritsar now?” She must have been from Amritsar. I looked outside the window. All I could see was white clouds. But in order to look knowledgeable, I said, yes, we were flying over Amritsar. I didn’t feel guilty for lying. I had made someone happy.

The plane stopped in Tehran, Rome, and Frankfurt before arriving in London. A cab whisked me away to a small hotel, courtesy of Air India, in the city. The hotel room was the cleanest I had ever stayed in and the bed was the most comfortable I had slept in. However, sleep I could not. I tossed and turned all night thinking about Gallaudet College and wondering how things would be there. How would they treat me? What was I going to do when my $50 ran out? That was more than my salary for a month as a photographer in India, but it would not go far in the United States. This was the amount allowed in foreign exchange and that I had received using money from my savings and an uncle’s gift. Would I be able to keep up with other students? These thoughts scared sleep away. I was also thinking about Big Ben, the London Bridge, Piccadilly Circus, Hyde Park, and all of those places I had read about and seen in photographs. I wanted to see them all. However, I had only a few hours the next morning. At about five in the morning, I got tired of trying to sleep and got up; showered; dressed in the same suit, shirt, and tie I had worn during the flight; and found my way to the dining room. There was no one there except a waiter. He asked me how I liked my eggs. That was a strange question. Eggs to me were eggs. The only words related to eggs I knew were “boiled” and “omelet.” So I asked for an omelet and he asked what kind. I didn’t know the types of omelets but also didn’t want to show my ignorance, so told him with the air of someone who specialized in omelets, I want an egg omelet. Later, I learned he had given me scrambled eggs.

After a hearty breakfast, I approached the concierge and asked him how to get to Piccadilly Circus. He wrote down directions for getting to the tube station and which station to go to from there and what to do after I got out. He was thorough. Armed with his instructions, I visited several sites in London without getting lost.

It was a surreal experience thinking I was one of those people who had seen all of those famous landmarks. When I worked in the Goyle Photography Studio, I had developed photographs showing people standing in front of various London landmarks. I was jealous of them. Now, I was there! I walked with a swagger. I wished I could get myself photographed in front of one of the monuments to send home. I didn’t have a camera and I didn’t know anyone with a camera within a five thousand miles radius. At that thought I smiled: my world was broadening.

But those landmarks were not what I had expected. Trafalgar Square was full of statues and, surprise, pigeons. There was nothing about Lord Nelson and his glorious naval victory. Hyde Park was just a park and Piccadilly Circus was a busy marketplace not much different than Connaught Place in New Delhi. I didn’t let myself admit that these places had a halo effect because of what I had read about them.

The concierge had told me to be back before 1:00 p.m. for a ride to the airport. I made it fifteen minutes before that. I was hungry and asked for lunch. No, he said, the airline had paid for my breakfast only. I had to wait and eat in the plane or buy my own food. Having already read the menu in the morning, I decided to skip the lunch. I already had spent more than $4 in tube and admissions. My funds were dwindling fast. It was time to tighten the belt, literally.

It was a crisp fall day when the TWA plane I had boarded in London landed at Dulles Airport in Virginia. I had a splitting headache and the bright fall sun made my eyes water. I lined up behind other passengers for customs and immigration checks. I was not sure what lay ahead, and in order to avoid making any mistake, I looked around for any instructions on how to go through immigration. There were none. A lady with a clipboard caught my attention. She would look at her clipboard and shout something as she scanned the passengers in the line. I decided to go read for myself what she was telling us. After gesturing to the passenger behind me to watch my attaché case and bag, I walked to where the lady stood. I maneuvered behind her and looked at her clipboard. It was a list of passengers, and I saw my name encircled in red ink with the word “DEAF” written next to it. I tapped the woman and pointed at my name. She looked relieved. Apparently she was yelling my name in the hope that the deaf guy would hear her.

She was of great help. After learning that I could not lipread, she used a pencil and paper to tell me that she was going to help me go through immigration and customs. I didn’t have to stand in the line. Deafness has its advantage. She took me to a closed counter and talked to the supervisor, who looked through my passport and stamped it with a smile. I thought about the rude, slow, and unfriendly immigration personnel I had dealt with in New Delhi compared to their U.S. counterparts. The efficiency, friendliness, and the “may I help you?” attitude were simply overwhelming.

Then she took me to the baggage claim area. The luggage carousel fascinated me. Bags of all shapes and sizes were going around and around and people were picking up their bags. There were no coolies—the ever present laborers who carried bags in India. Americans seem to do all their work themselves. We waited for my little bag to make its appearance. Finally the carousel stopped, and I learned that my bag was still somewhere between India and the United States. With the clipboard lady’s help, I filled out the forms they gave us, picked up my tote bag and small attaché case, and walked outside. I paid $2.50 to the driver of the airport bus that was to take me to Washington, DC.

Up until then, my vision of America consisted of cowboys trotting on their sorrels and pintos through the purple sage and mesquite. I also had seen some movies starring Gary Cooper, John Wayne, and others riding fast horses, shooting guns, cleaning up towns of black-hatted bad guys, and riding into the sunset for yet another adventure. The lush Virginia countryside along the Dulles access road was very different than the America I had envisioned. Imagine my disappointment at not seeing any cowboys or horses. There were, however, more important things to worry about, and I decided to forget the missing cowboys and horses for now.

I had about $43 in my pocket, two pairs of clothes, a pair of shoes, and the clothes on my back. I didn’t know anyone in the whole country and didn’t even have a letter of introduction. There was little or no hope in my mind of getting the bag containing all my worldly possessions—two suits, four shirts and four pairs of pants, underwear, and socks. A few gifts for people who might help me completed the contents of my small bag. It was all gone.

The bus dropped me at 12th Street, NW. And now I faced the problem of getting to Gallaudet. I tried to talk to people like I always did in India but found no one understood me. A huge black porter was helpful. He asked me to write. In the past, hearing people had always written to me and I always responded with my voice because I was understood. I never had to write to express myself. This was a new experience. My speech was not good in America! I had never heard English spoken, especially by an American; therefore I had no idea, and still do not, how Americans speak. My heavy Gagret accent had made my speech unintelligible in America.

The cab driver and the porter didn’t know where Gallaudet College was. I gave them the address and the cab driver shook his head and drove away after taking a look at it. Apparently, Gallaudet College was not situated in an area that cab drivers liked to go. The helpful porter made getting the cab for me his personal mission. He waved for another and talked to the cab driver who opened the back door for me. As the cab drove, I noticed the difference between Indian and American cabs and drivers. The driver sat relaxed and used the index finger of his right hand to steer. I didn’t know about power steering, so I wondered how strong his index finger was. As he stopped at a light and then started again, I was puzzled, as he never shifted gears. I craned my head and noticed there was no clutch, either. American cars and drivers were funny, I thought.

I had practiced the American Manual Alphabet on the airplane and felt very comfortable with the speed I could spell. I was confident that I would be able to communicate with American deaf people easily and flexed my fingers.

The cab entered Gallaudet campus and the cab driver stopped in front of a huge building, which I later learned was College Hall. I saw about thirty students milling around, signing to each other with the speed of lightning. The cabdriver asked me where I wanted to get off. I told him this place would be fine and got out. I stood there with the Air India handbag at my feet and gaped at the students walking and running around signing so animatedly. I could not understand even one word. I ...