- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

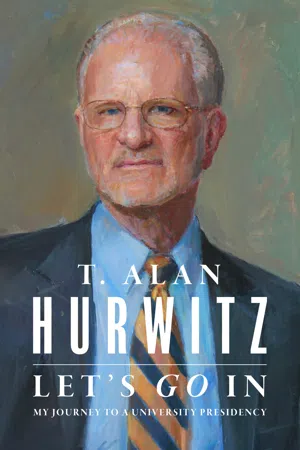

Alan Hurwitz ascended the ranks of academia to become the president of not one, but two, universities—National Technical Institute for the Deaf at Rochester Institute of Technology and Gallaudet University. In Let's Go In: My Journey to a University Presidency, Hurwitz discusses the unique challenges he encountered as a Deaf person, and the events, people, and experiences that shaped his personal and professional life. He demonstrates the importance of building a strong foundation for progressive leadership roles in higher education, and provides insights into the decision-making and outreach required of a university president, covering topics such as community collaboration, budget management, and networking with public policy leaders. He also stresses that assessing students' needs should be a top priority. As he reflects on a life committed to service in higher education, Hurwitz offers up important lessons on the issues, challenges, and opportunities faced by deaf and hard of hearing people, and in doing so, inspires future generations of deaf people to aim for their highest goals.

Additional images, videos, and supplemental readings are available at the Gallaudet University Press/Manifold online platform.

Additional images, videos, and supplemental readings are available at the Gallaudet University Press/Manifold online platform.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Let’s Go In by T. Alan Hurwitz in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781944838638Subtopic

Education Biographies1

“You Can Be Anything You Want to Be”

DURING THE INTERMISSION, I excused myself to go to the men’s room. When the swinging door closed behind me, my Blackberry started to buzz—and kept buzzing. Incoming was a long list of texts from Ben Soukup and Frank Wu, chair and vice chair, respectively, of the Gallaudet board, who had been trying to reach me for over an hour. They wanted to meet with me right away. Where was I? they wanted to know. Flustered, I stood at the sink and responded, texting them that I’d been in a hotel ballroom with no cell reception all evening. “We’d like to talk to you right away,” they replied. I texted back: “OK, I’ll find a way back to my hotel now, but there are hundreds of people at this event, so it won’t be that easy to leave inconspicuously.”

“That’s understandable,” they texted, “but come as soon as you can.”

Back in the ballroom, I tried to get my wife Vicki’s attention. Characteristically, she was surrounded by a crowd, talking with her friends. Her sociability and interest in people, usually something I especially love and admire in her, frustrated me at that moment. Couldn’t she be more retiring? More standoffish, so that it would be easier to extricate her quickly from crowds when time was of the essence? She finally saw me, and I silently—and I hoped unobtrusively—mouthed to her that we needed to leave right away. “What for? Why?” she asked. I mouthed again, “We have to leave. Don’t argue with me.”

I remembered that our daughter was in the hallway outside the ballroom, so I added, “Stefi wants to see you in the hall. And bring our coats!” Of course, when we got into the crowded hall, Vicki and Stefi saw each other and immediately began what looked like a leisurely conversation. I gently tugged Vicki away but still couldn’t explain why we had to leave so abruptly. A ride down the slow escalator to the lobby deposited us into another large crowd of deaf people because the event was a Deaf community function, sponsored by Purple, a video-relay services vendor. “Hello!” “Hi, how are you?” “Good to see you, Dr. Hurwitz!” “Have you gotten any news about the search decision yet?” We smiled as we made a beeline to the exit. I felt perspiration gathering on my forehead.

Earlier in the day, I’d had my first meeting with the Gallaudet University Board of Trustees (after two earlier meetings with the search committee and one campus-wide public meeting), and this was my third visit to Gallaudet as a presidential candidate. When the meeting had ended at two-thirty, Ben and Frank had asked me to meet with them privately in the next room.

“We’ll be making our selection this afternoon,” Ben said, “and so our last question of you and all the other candidates is this: If you are selected, will you accept our offer?” I’d known I was past the point of no return. I did want the job and would accept it if it were offered to me. It would be the leadership opportunity of a lifetime, a thrilling cap to an already unexpected career. “Yes,” I said.

Later, at lunch with my wife, I shared everything with her, including my assessment of my chances. I’d done well, I thought, at my last interview. The board members and I had been candid and comfortable in our discussion of how critical a time it was in the university’s trajectory, with a newly written strategic plan and the selection of a president to manifest the plan through organizational leadership. “It will be a tough decision for the board,” I told her, “because the other finalists are such outstanding candidates.”

The others were Dr. Stephen Weiner, provost of Gallaudet University; Dr. Roslyn Rosen, director of the National Center on Deafness at California State University, Northridge; and Dr. Ronald Stern, superintendent of the New Mexico School for the Deaf. Since all were either alumni of Gallaudet or current leaders, I had initially wondered why I was included in the final pool, especially since I had not attended Gallaudet. It also occurred to me that not being selected as Gallaudet’s president might be a blessing in disguise because it would mean I could remain at the National Institute for the Deaf at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT/NTID), where I’d happily spent nearly forty years of my career. But after the months of interviews—meeting with large groups of lively, engaged Gallaudet students, meeting faculty and the board of trustees, seeing the campus, imagining ourselves living in this city, and leading this vibrant university into its next promising chapter—the prospect of having RIT/NTID as the last stop on my professional journey paled.

Outside, it was still pouring rain, and there was a long line of folks waiting under the hotel portico for a cab. Red and green and blue lights reflected on the wet sidewalks and streets. As soon as I saw an opening in the taxi line, we cut in, excusing ourselves, and finally got into a car. We were on our way at last! I wrote a note to the driver to take us to our Marriott hotel a mile away, and then I showed Vicki the long list of texts on my Blackberry. Her face showed alarm and apprehension that matched my own.

I texted Ben and Frank that we were finally in a cab, and they responded that they were in the bar on the second floor of the Courtyard Washington, DC/US Capitol hotel in the NoMa district. “Should I come alone?” I texted. If they said yes, that might be an indication they’d decided not to select me and didn’t want to break the bad news with my wife there. They texted back: “No, bring Vicki, and we’ll all have drinks together.” That seemed like a good sign.

Ben and Frank were nursing cocktails when we arrived, sitting around a large table by the bar, next to a window that looked out onto city lights blurred in the rain. Smiling, they urged us to order drinks too. When the waitress returned from the bar with our glasses, Ben grinned widely and said at last, “Alan, I’m delighted to let you know that the board has decided to appoint you as the tenth president of Gallaudet University!”

Vicki and I turned to look at each other, completely stunned. I looked questioningly around, and Vicki said, “Yes!” Ben smiled and asked if we were surprised. When we said yes, he said, “Let’s celebrate,” and toasted us.

The vice chair, Frank Yu, then produced a contract for me to review and sign. When I’d read it, signed my name, and pushed the contract back across the table to him, Frank said, “Did you have a nice lunch at Five Guys?” Vicki and I again looked at each other, puzzled, and asked how he’d known that we’d grabbed lunch at that burger place earlier in the day. He grinned and said it was posted on Twitter by a student member of the presidential search committee. Our lives had shifted into a new phase, a very public one. Our privacy was shot for the foreseeable future.

Still dazed, though thrilled and happy, Vicki and I went up to our room and texted our children the good news, asking them to keep it to themselves until after the announcement. I immediately went to work on my acceptance speech at the round table in the corner of our hotel room, staring at the blank screen of my laptop for a moment, conscious of a feeling of great joy and gratitude. My mind kept returning, for some reason, to my father, who always proudly referred to me as “my boy.” What would he have thought, to see his boy about to take the reins of the world’s premier institution of learning and research for deaf and hard of hearing scholars and students, the first born-deaf person to lead the school? I could picture his face, his loving look, and reassuring smile, his confidence in me. My parents’ spirit of pride and optimism had a lot to do with where I found myself now.

2

Our Roots

LIKE ME, both my parents were born deaf (or had been deaf as long as they could remember), but unlike me, they were born into hearing families. My paternal grandparents, Ben and Rose, hadn’t known anything about raising deaf children, nor where and how deaf children could be educated, so they kept my father and his hard of hearing sister, my Aunt Cranie, at home above their grocery store in Sioux City, Iowa. They were Yiddish and Russian speakers with very little English, who found it doubly difficult to communicate with or about their deaf children who were growing up in an English-speaking country.

My mother’s grandparents and my father’s parents all came to the United States from Central and Eastern Europe in the 1800s. Like most European Jews of the time, they made the trip to escape poverty and persecution. My paternal grandfather, Baruch Gurevich, was born on September 29, 1885, in Chavusi, Belarus. He escaped from Czarist Russia in the late 1890s and landed at Ellis Island in New York. He couldn’t read or write English. When the clerk asked his name, he might have thought my grandfather said “Hurwitz,” and that became his legal name. His first name, Baruch, was changed to Benjamin, and everyone called him Ben.

Although he worked as a tie peddler at first, Ben had an adventurous spirit and soon joined the wave of western migration, probably with intentions to dig for gold. On his way to California, he stopped in Sioux City, Iowa, where he met a young woman named Rose Mazie, my grandmother. She had also been born in Belarus, on February 20, 1892, in Klyetsk, Minsk, and had arrived in America with her parents in the mid-1880s, where they settled in Iowa for reasons lost to us now. Her parents most likely had connections among the large Jewish immigrant community in Sioux City. (Their neighborhood was home to famed twin advice columnists Pauline and Esther Friedman, whose syndicated columns were known as Dear Abby and Ask Ann Landers, and whose parents were Russian Jewish immigrants as well.)

Since my father’s sister, Aunt Cranie, had some usable hearing, she could lipread her parents better than my father could. My father, however, never learned Yiddish, and his communication with his own parents and neighbors was limited to gestures.

I don’t know what would have become of my father if his life had stayed on this limited path. Luckily, in 1926, when he was thirteen years old, my grandparents learned about the Iowa School for the Deaf (ISD), and they enrolled him there. The school was eighty miles south in Council Bluffs, so my grandparents drove him to the school every fall and picked him up for the holidays in December and the summer months. Finally, he was receiving a formal education. It did not take my father long to learn sign language, make many friends, and become an outstanding student and a standout basketball player who also loved playing tennis and baseball. He loved ISD and thrived there, but his sister, who attended ISD for one year, was unhappy at school and returned home to public school in Sioux City, where she dropped out before graduating high school, a very common outcome for a deaf student in the 1930s.

Ben and Rose Hurwitz, my paternal grandparents.

ISD, like many other residential schools at that time, had a rigorous academic program. My father took high school courses in English, mathematics, chemistry, and physics. He also took several vocational courses that prepared him for jobs as a baker, Linotype operator, and furniture maker. Graduating at the age of twenty-five, he took the entrance exams to attend Gallaudet College and passed. But soon, new circumstances, and his priorities, would keep him from ever attending.

MY MOTHER, JULIETTE, was born on January 15, 1916, the daughter of two first-generation Kansans. Her mother, Rosaline Berlau, was a native of Leavenworth, Kansas and the daughter of two Polish immigrants. Her father, a dashing man named Tobias Kahn, was the son of immigrants from Bohemia. My mother was always an active child, playing ball, loving to climb trees, and preferring the outdoors to staying inside. In contrast, her hearing sister, Sylvia, was a bookworm. But the two sisters were always close.

How my mother became deaf and whether she was born hearing remains unknown. My grandparents did not realize she was deaf until she was five years old, when a deaf nine-year-old neighbor, Elizabeth Shannon, told them she thought Juliette was deaf. Soon after, my grandparents enrolled her at the Madison School in Kansas City, which had an oral program for deaf children. My mother and her sister communicated well because Sylvia was an excellent lipreader.

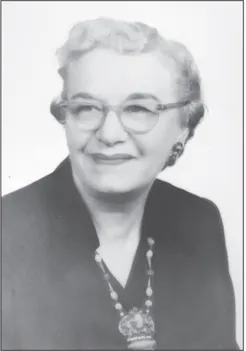

Roslyn (Ga-Ga) Kahn, my maternal grandmother.

And then, when my mother was ten, her parents sent her to the Central Institute for the Deaf (CID) in St. Louis. The school had opened its doors just a little over a decade earlier, in 1914, and was founded by Max Aaron Goldstein, an Austrian-educated American physician. He aimed to teach deaf children to speak orally. By the time my mother was sent there, the school had erected new buildings and had a wait list for enrollment. Unfortunately, after about a year at CID, she became very ill with thyroid problems and left to have surgery and recuperate. She spent the remainder of her middle school education at the Madison School back at home. But when she was seventeen, she asked her mother, my grandmother Rosaline (we called her Ga-Ga), if she could return to CID, where my mother felt that she could get a better education. In all her years at school, my mother still had not learned to read! When she saw Sylvia with her nose in a book, she sometimes wondered what that would feel like to be able to sit for hours, immersed in a story. What was the trick to reading, she wondered?

Her primary teacher upon her return to CID was Mrs. Jessie Skinner, the mother of deaf twin sons who were also CID students. Mrs. Skinner struggled to teach my mother how to read, but with little success. Finally, Mrs. Skinner told my mother that if she didn’t become literate, she would be sent home. Terrified, my mother picked up the novel Little Women, determined to read it word by word. It was slow going at first, but after a while, she began to visualize the story of the four March sisters—their cozy house, their loves and literary ambitions, Beth’s battle with illness, and the dramatic plays Jo wrote and directed in the attic. When my mother began to picture the characters and settings in her mind, she was finally inspired to keep reading, to stay in that world, and discover what happened next. She told me that as soon as she finished Little Women, she picked up a second book, and then another. Soon, like Aunt Sylvia, she was a true fan of reading, and it was a love that would last her whole life, and one that she would work steadily to instill in me.

Tobias Kahn, my maternal grandfather.

When she graduated from CID, my mother entered ninth grade in a public school in Kansas City. By then, she was nineteen and thought herself too old to be in high school, so she left after just a few months and went to work.

It was a few years later that she met my father, who was visiting his aunt, Elizabeth Mazie Shapiro, in Kansas City. Aunt Elizabeth knew my mother’s great-aunt Emma Berlau, so they played a role in introducing them to each other.

My father had just graduated from ISD and planned to attend Gallaudet College in Washington, DC, at the end of the summer. Although my mother didn’t know sign language and my father didn’t speak or lipread, they somehow managed to fall quickly and deeply in love. How they communicated with each other is a mystery. My father decided to forgo his college education in favor of settling down with my mother, and they married on October 6, 1938, when my mother was twenty-two years old, and my father was twenty-five. Over time, my mother became proficient in sign language, and my father learned how to lipread my mother. It takes two to tango, I guess!

Soon after the wedding, they moved from Kansas City to Topeka, where my father got a job as a Linotype operator at a newspaper. After one year, they moved to Orange City, Iowa, where he again worked as a Linotype operator. They stayed in Orange City for three years before moving to Sioux City, where my father got a job as a baker, another skill he had learned at ISD. They lived with my father’s parents for a while before moving to an apartment on Pierce Street. My mother was a homemaker, and she soon learned her way around Sioux City and made new friends in the Deaf community.

On September 17, 1942, I was born, their first and only child. Following the Jewish custom of naming children after a deceased family member, typically using the first initial of the person’s name, my parents decided to name me after my mother’s father, Tobias Kahn. He got the H1N1 virus in the 1918 pandemic and died of rheumatic fever and a heart attack (a common complication of the virus) just before my mother’s sixteenth birthday when he was only forty-seven years old. Later, my father told me that they’d wanted to name me Thomas or Theodore, but they couldn’t pronounce either name well enough to be understood by the attending nurse. She wrote down “Tracy?” and my mother liked it. My parents then added Alan as my middle name, since my paternal grandfather’s middle name was Allan, and my father’s middle name was Allen.

SIOUX CITY, a medium-sized city in the flat grasslands of northwestern Iowa, i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. “You Can Be Anything You Want to Be”

- 2. Our Roots

- 3. At Home at the Central Institute for the Deaf

- 4. Public School in Sioux City

- 5. A Good Day’s Work

- 6. Love at Second Sight

- 7. Deaf at a Hearing College

- 8. A Perfect Match

- 9. Early Marriage

- 10. Forks in the Road

- 11. A Lifetime Commitment

- 12. “Get Busy!”

- 13. Bernard and Stefi

- 14. Advocacy for Access

- 15. A Chance to Lead

- 16. Our Pop-Up Camper

- 17. My First 100 Days at Gallaudet

- 18. Big Ideas

- 19. Difficult Decisions

- 20. Heart Troubles

- 21. Farewell to Gallaudet

- Afterword

- Where Are They Now?