eBook - ePub

Interpreting in the Zone

How the Conscious and Unconscious Function in Interpretation

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Successful interpretation can feel seamless, an intuitive and efficient translation of meaning from one signed or spoken language to another. Yet the process of interpretation is actually quite complex and relies upon myriad components ranging from preparation to experience to honed judgment. Interpreting in the zone, instinctively and confidently, is an energizing, encompassing experience that results in great satisfaction and top performance—but what does it take to get there?

Jack Hoza's newest research examines the components that enable interpreters to perform successfully, looking at literature in interpretation, cognitive science, education, psychology, and neuroscience, as well as reviewing the results of two qualitative studies he conducted. He seeks to uncover what it means to interpret in the zone by understanding exactly how the brain works in interpretation scenarios. He explores a range of dichotomies that influence interpretation outcomes, such as:

- Intuition vs. rational thought

- Left brain vs. right brain

- Explicit vs. implicit learning

- Novice vs. master

- Spoken vs. signed languages

- Emotion vs. reasoning

Cognitive processes such as perception, short-term memory, and reflexivity are strong factors in driving successful interpretation and are explored along with habits, behaviors, and learned strategies that can help or hinder interpretation skills. Hoza also considers the importance of professional development and collaboration with other practitioners in order to continually hone expertise.

Interpreting in the Zone shows that cognitive research can help us better understand the intricacies of the interpreting process and has implications for how to approach the interpreting task. This resource will be of value to both the interpreter-in-training as well as the seasoned practitioner.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Interpreting in the Zone by Jack Hoza in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Gallaudet University PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9781944838799, 9781563686665eBook ISBN

97815636866721

THE INTERPRETER BRAIN AT WORK: THE CONSCIOUS AND THE UNCONSCIOUS

The act of interpreting is a remarkable task. Wilcox and Shaffer explain that interpretation is a creative process in which “interpreters construct meanings, make sense, and hope that the sense they made somewhat captures the sense intended.”1 This process is a gargantuan task, as communication and human interaction are so complex. People do not have access to each other’s thoughts and intentions, so they use language as well as other means of communication, such as body language, intonation, and gestures, to construct meaning. When an interpreter is part of the process of co-constructing meaning, communication and interaction are even more complex.

Think of the number of times you have misconstrued what someone said when you both were using the same language, and you quickly realize that it is a wonder that interpretation can be successful at all. Yet this feat happens every day in the world of interpreted interaction. Although misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and confusion are bound to occur, it is surprising that interpretation can work as well as it does.

I am reminded of a particularly challenging interpreting assignment I had many years ago when I interpreted Shakespeare’s King Richard III at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. Another interpreter and I teamed up to interpret this complex play, and we spent many long hours translating and practicing our American Sign Language (ASL) rendition of this artistic piece. We analyzed the characters’ motives, attended to the development of the storyline, and scrutinized the myriad levels of meaning that is common in a Shakespearean play.2

On the night of the performance, we dove into the live interpretation, and I remember that interpreting this play was one of the first times that I realized there was something intuitive and magical about interpreting. The interpretation resulted in natural discourse and expressed deep levels of meaning, even though it was such a challenging play. Our interpretation seemed so effortless at the time, and we were so energized; it was as though we just knew what to do, and it fell into place. We were able to quickly resolve any glitches and were especially creative and “in the moment,” and the interpretation, overall, felt seamless. We were “in the zone,” which was an incredible experience.

This sense of being “in the zone,” or “in flow,” became a more common experience as I gained more experience as an interpreter, and it was a state that I tried to achieve more often in my interpreting work. However, it was interpreting that challenging play that first opened my eyes to this phenomenon that was so difficult to describe and that I did not have a name for at the time.

Experts in a variety of fields can have an in-the-zone experience, which typically signals success in one’s discipline and does not just happen in a hit-or-miss fashion. This type of experience in one’s discipline results from many factors that take years to develop. Interpreters do not always understand how getting in the zone comes about, but they certainly know it when they see it or experience it first-hand. It is something that newer, or novice, interpreters are sometimes puzzled by, because constructing meaning in an interpretation seems like such a great deal of work for many of them. How could it look so easy when the interpreter is dealing with such myriad levels of meaning and contextual factors?

As an interpreter and interpreter educator, I have always been interested in how interpreters manage to achieve what they do as interpreters and what can cause the interpretation not to work. My purpose in writing this book is to explore how the interpreter brain functions when interpreters are in the zone and to describe how novices and experts differ in how they manage complex cognitive tasks, such as constructing meaning, managing interactive factors, and making important professional and ethical decisions. My hope, overall, is that the reader will achieve a better understanding of how interpreters can get in the zone, how they can stay in the zone, and how they can manage their work when conditions are such that they find themselves on the edges of the zone.

Professionals are aware of the complexities of their respective fields. Successful attorneys, teachers, and architects seem to have a sense of both the art and science of their fields of expertise. They can know what to do at a particular moment, because they have the necessary knowledge, training, experience, and honed judgment. This book is about an interpreter’s knowledge and honed judgment, how an interpreter can have more in-the-zone experiences, and how the brain functions when an interpreter is in the zone.

Exploring the Interpreter Brain

Interpreting is a cognitive process. That is, it occurs in the human brain. Mental processes, such as perceiving, recalling information, constructing meaning, and decision-making, are primary components of interpreting. It behooves interpreters to know how the brain works. Auto mechanics could not do their job if they did not open the hood and check out the engine. This book is going to look under the hood, as it were. It will provide an opportunity to look at the mental processes of interpreters and the expertise needed to be successful interpreters.

The primary goals of the book are to

1. elaborate and demystify the cognitive processes that enable interpreters to accomplish the construction of meaning and decision-making in live interpretation,

2. provide practical ideas regarding how interpreters can best manage these processes,

3. provide better understanding of how interpreters can develop and further their abilities and skills, and

4. clarify how they can be more effective and caring practitioners.

Two Studies: An Interview Study and a National Survey

To better understand how interpreters get in the zone and what happens in the interpreter brain at these times, I conducted a literature review that covered disciplines, such as interpretation, education, psychology, cognitive science, and neuroscience. I also conducted two qualitative studies on the interpreting process.

One study involved filming novice and experienced ASL/English interpreters (n=12) interpreting the same interactive video of a meeting between a vocational rehabilitation (VR) choose-to-work specialist (a hearing, English speaker) and a VR consumer (a Deaf, ASL signer),3 and interviewing the interpreters afterwards. They were asked about their day-to-day interpreting work as well as about how they managed specific excerpts from their sample interpretation.

All of these interpreters were licensed to interpret in the state of New Hampshire and lived in either New Hampshire or neighboring states. The following three groups of interpreters were interviewed:

1. Four randomly selected novice interpreters, who were not nationally certified but held state-screening as interpreters for less than five years,

2. Four randomly selected professional interpreters, who had been nationally certified for more than 15 years, and

3. Four selected interpreters, who were nationally certified and had been selected by the majority of a group of 15 Deaf people who often work with interpreters and attend interpreted public events.

The other study was an online national survey of randomly selected, nationally certified ASL/English interpreters in the United States (n = 223). Respondents were asked a range of open-ended questions. They were asked about the cognitive (mental) process of interpreting, how they prepare for interpreting assignments, how they can tell when an interpretation is “working” or “not working,” strategies for making the interpretation “work” again, insights into their work (aha! moments), habits or strategies they have that help them with interpretation and habits they are seeking to change, and the differences between novice and experienced interpreters. Most of these same questions were also asked of the participants in the interview study.

The results of the two studies help clarify the cognitive processes involved in interpretation, how interpreters manage these processes, and how interpreters make related decisions. Although the national survey provided a broad view of these issues, the interview study provided opportunities to talk one on one with interpreters about these issues, which resulted in the specific examples and practical applications that are interspersed throughout the book.4

The Brain at Work: The Conscious and the Unconscious

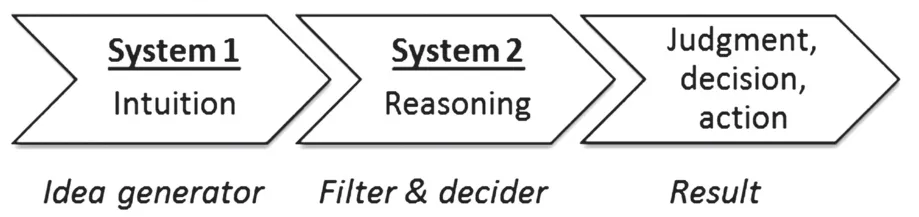

The conscious and the unconscious work quite differently in the human brain. Nobel Prize–winner Daniel Kahneman (along with his colleague Amos Tversky) spent more than five decades studying the conscious and the unconscious. Kahneman refers to the unconscious as System 1 and to the conscious as System 2 in order to clarify their respective functions.5 System 1 (the unconscious) is intuitive and automatic and quickly proposes thoughts, ideas, and actions to System 2 (the conscious brain). System 2, in turn, requires more deliberate attention and relies on explicit beliefs and reasoning to either accept or reject what System 1 proposes. Whereas System 1 is quite active, System 2 tends to be more passive and is inclined to accept what System 1 proposes (see Figure 1.1).6

Figure 1.1. This figure illustrates the functions of Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2.

The interactions between the unconscious and conscious mind—between intuition and rational thought—are evident in everyday events, such as driving a car. Much of what people do when they drive is not conscious to them. Rather than micromanaging when to accelerate, decelerate, or even make turns, their minds are usually preoccupied with other thoughts about their lives or their destination. As when driving, conscious minds attend only to highlights of what is occurring in one’s environment and make general decisions that are carried out by specific muscle groups or more automatic decision-making systems. Because novice drivers have fewer intuitions about driving, they need to make a more conscious effort when they drive. Experienced drivers, in contrast, may even slam on the brakes and start turning to avoid a collision before being consciously aware of the fact that a car has cut out in front of them.

Eagleman explains that people usually do not recognize much of the behind-the-scenes work that the unconscious brain does, and are only conscious of the “headlines” of its work.7 He explains, “You are not consciously aware of the vast majority of your brain’s ongoing activities, and nor would you want to be—it would interfere with the brain’s well-oiled processes.”8 Many acts, such as typing on a keyboard, parallel parking, or carrying on a conversation in one’s native language depend on procedural memory, or implicit memory, which is knowledge that people have but do not consciously access. Eagleman gives a fascinating example of how a batter hits a fastball. A fastball travels the distance from the pitcher’s mound to the batter in 0.4 seconds, but it takes 0.5 seconds to actually perceive that a pitch is, in fact, a fastball. This example clearly demonstrates that the unconscious can be fast and not under people’s conscious control, and yet can serve them well.9

Gladwell explains that the unconscious can quickly recognize patterns in situations and in behavior based on very narrow slices of experience, which he calls thin-slicing.10 He gives the example of a Greek sculpture that was deemed authentic and was purchased for 10 million dollars by the J. Paul Getty Museum. However, several art experts sensed within seconds of seeing the sculpture that it was not genuine, and, indeed, it was eventually deemed a forgery. He gives another example of John Gottman, a marital expert, who could observe couples for 15 minutes and tell with 90% accuracy whether or not the co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Interpreter Brain at Work: The Conscious and the Unconscious

- 2 Many Pieces to the Puzzle: Understanding the Interpreting Process

- 3 The Interpreter in the Zone (and Other Zones)

- 4 From Novice to Expert, and Two Kinds of Expertise

- 5 Making Changes in One’s Interpreting Work: Habits and Aha! Moments

- 6 Bilingualism, and Mainstream and Community Approaches to Interpreting

- 7 In the Zone, Out of the Zone, and Getting Back into the Zone

- 8 Positionality, Identity, and Attitude

- 9 Decision-Making and Processing with Others: The Journey Continues

- Appendix 1: Description and Limitations of the Two Studies

- Appendix 2: Interview Questions

- Appendix 3: Demographics of the Interview Study Participants

- Appendix 4: The National Survey

- Appendix 5: Demographics of the National Survey Respondents

- Appendix 6: Results of the National Survey

- References

- Index