![]()

Other Stories: Places of Memories, Places to Change

Katrin Kivimaa

![]()

Zone

Tallinn old industrial zone

![]()

One reference for the title and theme of this work is Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (1979) which was shot in and around Tallinn, Estonia — then part of the Soviet Union. The film is based on Roadside Picnic, a Russian science fiction novel (by Arcady and Boris Strugatsky). It follows the journey of two men led by ‘the stalker’, the guide who takes them through ‘the zone’, a geographical space contaminated by an alien presence. The zone is supposed to have a room where those who enter have their every desire fulfilled ... whatever it is. The two men baulk the threshold of the room in fear of the final realization of what was their actual unconscious desire. Terrified by the thought of what their desires really are and what it will bring to their lives, they opt for the certainty they already know and return home without entering the room. In this respect the film works, in my view, as a metaphor for an encounter with capitalism and forbidden desire in Soviet culture.

In ‘post-Soviet’ European culture, ‘the West’ marks its presence as the dislocation of old boundaries, creating new certainties and uncertainties. Today Estonia is an independent state, having gained autonomy from the Soviet Union in 1991. The ‘zone’ is no longer only a metaphorical space, it is where people actually have to negotiate their desire within the ‘alien’ rules of capitalism. The photographs in Zone are taken in and around Tallinn where Stalker was filmed. The Western viewer can consider the image of the so-called ‘East’ as a new unfamiliar zone of capitalism, or (as any viewer) to engage with the question of space in these new and old certainties. In these images it is the colours, figures, and spaces of the images that can be allowed to speak their desire.

![]()

Stalker

![]()

TypeWriter

![]()

Gathering Crowd

![]()

Melting Ice

![]()

![]()

Window Dressing

![]()

Making Progress

![]()

Zone

![]()

Snow White

![]()

To Finland (from Kadriorg)

![]()

Lenin Alarm

![]()

Waking Vision

![]()

Home

![]()

Dawning Light

![]()

Buds (Spring)

![]()

McDonald's Sign

![]()

Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, USA, 2006 Installation view (small version)

Zoneography

C-Type colour photographs (from 35mm film)

Exhibition Print dimensions: 96x108cm (or 65x100cm)

Zone Exhibitions/Publications

| 2001 | Linna Galeriis, Tallinn, Estonia |

| 2002 | Watershed Gallery, Bristol, UK, April–May |

| 2002 | Focal Point, Southend-on-Sea, UK, August–September |

| 2002 | Belfast Exposed, Belfast, Ireland, October–December |

| 2003 | Archetype, Brussels, March–May |

| 2003 | Galerie le lieu (15th Rencontres Photographiques), Lorient, France, October– December |

| 2004 | London Gallery West, London, UK, February–April |

| 2006 | Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, USA, March–May |

| 2006 | 1st International Photography Biennale (IFSAK), Istanbul, Turkey, September–November |

| 2007 | Contemporary Art Projects, London, UK, April–June |

Publications/Reviews

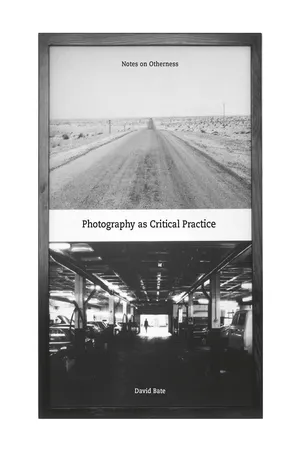

David Bate, Zone (London: Artwords Press, 2012).

‘Zone’, in Katrin Kivimaa, Kinnitused Ja Vastuvaied (Tallinn: Kunst.EE, 2008).

Robert Bird, Andrei Tarkovsky: Elements of Cinema (London: Reaktion Press, 2007).

Eugenie Shinkle, ‘Boredom, Repetition, Inertia: Contemporary Photography and the

Aesthetics of the Banal’, Mosaic, 37 (2004).

David Bate, ‘Zone’, in Transmission: Speaking & Listening, ed. by S. Kivland, L. Sanderson and E. Cocker, vol. 3 (Sheffield: Site Gallery/Sheffield Hallam University, 2004).

Els Roelandt, ‘David Bate & Zone’, Ty (Flemish journal), 16 April 2003.

T. Roger-Pierre, ‘Zone: Metaphores urbaines’, Le Libre Culture, 2 April 2003.

Daniel Jewesbury, ‘Zone’, Matters, 16 (2003).

Aidan Dunne, ‘Zone’, Irish Times, 6 November 2002.

Alicia Miller, ‘Follow the Stalker’, Source, 33 (2002).

Jessica Lack, ‘Zone’, The Guardian, 17 August 2002.

Eve Killer, ‘David Bate: Institutional Spaces’, Kunst EE, 2002.

Katrin Kivimaa, ‘Tallinn kui tsoon’, Eesti Ekspress, 20 December 2001.

David Bate, ‘Zone’, Portfolio Magazine, 34 (2001).

![]()

Viru Hotel, Tallinn, Estonia

![]() The Other Side of Seeing

The Other Side of Seeing![]()

Zone is the story of a city at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The city had seen many changes, but new rules were changing the city again forever. The pictures in Zone relate to the story of Tallinn as a city haunted by the images of a film. The film, Stalker, tells the story of a writer and a scientist who go into an alien zone, where it is said a room exists in which anyone’s deepest desire will be granted. After the aliens had left many still feared this zone and its strange logic that few knew or understood. The zone could turn against you: it altered when someone moved through it, and so people found it hard to orient themselves within it. A guide was needed to find the stalker — who took the writer and the scientist into the zone. As they moved forward through it, the rules seemed to change, so that what seemed like moving in a straight line turned out to be going in a circle. Familiarity turned into strangeness, which quickly turned back into familiarity. Once the room of desire was reached, it was not what they expected. Fearful of their deepest unconscious wishes, they turned and went home. Only the guide was left; exhausted, neither wanting to enter nor to leave the zone. In each person, the zone had transformed them in relation to what they had desired. In the real city of Tallinn, people wondered if the aliens would ever return and change it all again.

To photograph

In everyday life, photography is a central medium through which we encounter and visualize ‘the world’. So, to say that photographs define the world is, in that context, quite true. To make a photograph, as a self-conscious decision or as an automated process, is an act that makes a gesture towards space. This space, made into a picture through the coordinates of geometry (the perspectival geometry of a lens) recorded in a camera, establishes a set of relations for the viewer. The viewer’s point-of-view is given by the camera-photograph relation, from which s/he is offered a scene to occupy, as in a virtual dwelling.

In this spectral place, the encounter with a photograph functions as a potential space for otherness. The photograph offers a psychological space where otherness is located as a stilled scene, an image culled from lived reality that is both familiar and different. A photograph makes these other spaces familiar through the repeated experience of the codes of the encounter. Flanked on one side by the art of painting and on the other by the industries of the moving image, still photographs offer a pivotal space, caught between different technologies, modes of image-text-sound movement, and a stasis of communication. Our mixed encounters of these various forms are normalized through words, speech, sounds, and the multitude of images we encounter daily. Formulated in the cacophony of the jungle of media messages, the space of otherness in photography (as a form), its very stark strangeness, is worn weary with familiarity, through daily repetition of the same structures, meaning, and scenes. In this daily grind of the familiar, what might it mean to see something one does not understand?

The unfamiliar

The act of making a photograph in an unfamiliar place is an instructive one. In an unfamiliar place it is not only that one’s bearings may be lost, but also that the space itself is something quite unfamiliar or strange. At that instant the question of ‘what-is-to-be-photographed?’ is raised. This type of situation, a miniature instance of disorientation, may be almost the equivalent of the posing of a philosophical question, about belonging, representation, and the issue of identification: where am ‘I’?

With the decision to make a photograph in an unfamiliar place, the quick choice often made at that instant, when it is too late to think about it in depth, is to point the camera at an already familiar object. A common ‘tourist’ solution to this unfamiliar situation is to point the camera at something familiar and recognizable, like the figure of a friend, acquaintance, family member, or well-known landmark. Such figures point to the already known. The picture of a friend in a strange place — or better still, in front of a known landmark — marks a turn, a return to something completely familiar. A famous landmark or monument by which that place is specifically known, signifies something already familiar, that is, familiar, even if that person has never actually visited it before, because it is the image of that landmark/place that is already known. In this way, one type of tourist picture finds a solution to the question of unfamiliarity by making things familiar. The concept of recognition is a key component in this process. Recognition is a re-cognition. ‘To recognize’ involves the cognitive process of seeing something already known, already familiar. Such evocations of the familiar — and the compulsions to repeat them — evade and evict the encounter of otherness.

Whether intended or not, seeing is reduced to a knowledge of the already known, where newness becomes merely a repetition of the same. An alternative to this tendency to turn towards something familiar is to challenge the very status and pleasure of these processes of recognition, whether it is in...