![]()

PART ONE Provocations (1821–1852)

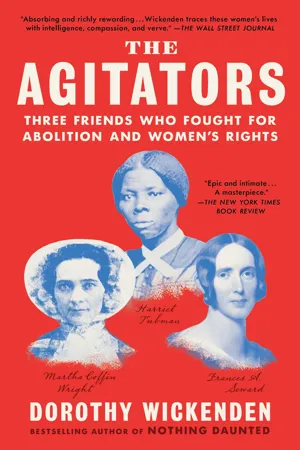

The Miller-Seward family, ca. 1846

![]()

1 A Nantucket Inheritance 1833–1843

Martha Coffin Wright, 1820s

Martha Coffin Wright’s mutinous mind had its origins in a place she never lived: a jagged fourteen-mile-long fishhook of an island thirty miles off the coast of Massachusetts. She rarely encountered an institution she didn’t question, and although convention dictated most of the circumstances of her life, she liked breaking rules, and then explaining why she had no choice. Her parents, Anna Folger Coffin and Thomas Coffin, were Quaker descendants of two of the first English settlers who had fled the Massachusetts Bay Colony rather than submit to the fines, floggings, and prison terms the Puritan clergy imposed on anyone who bucked church dogma. The women of Nantucket took for granted their equality with men. Mary Coffin Starbuck, Martha’s great-great-grandaunt, ran the island’s first general store, out of her house on Fair Street, and traded with the Wampanoag Indians: tools, cloth, shoes, and kettles in exchange for fish and feathers. In 1708, Starbuck organized the island’s first meeting of the Society of Friends, and she became a minister, a position closed to women of other denominations. The Nantucket Quakers opposed slavery, which was legal in all thirteen colonies, holding early meetings to advocate abolition. As financiers of the whaling business, they were at once frugal and profit-minded.

The Coffin family was a matriarchy, headed by Martha’s mother, Anna, and Martha’s tiny but indomitable sister, Lucretia Coffin Mott, who was fourteen years older than she was. Anna kept her own small store and taught her children to oppose slavery and to practice “the Nantucket way,” the egalitarian social and business relations followed on the island. Martha’s father, Thomas, had been a whaling captain like his ancestors, one of the most dangerous professions in the world. A harpooned whale could eliminate a boatload of harpooners with a single thrash of its tail. In 1800, Thomas switched to the somewhat safer business of trading—buying sealskins in South American ports, and exchanging them in China for soft nankeen cloth and silk, tea, and porcelain. But he was still gone for years at a time, and he and Anna finally moved the family to Boston, where Thomas started an import business. Martha, the last of their five living children, was born there on Christmas Day in 1806. Three years later, the Coffins moved to Philadelphia, and Thomas bought a factory that produced cut nails.

Quakers in Philadelphia had their own anti-slavery tradition, but a fractious one. Many Friends owned slaves until 1775, when the city’s Quaker meeting called upon all members who hadn’t freed them to do so. That year, Quakers led the founding of the first abolition group in America: the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. By 1789, the elderly Benjamin Franklin—a former owner of two slaves—was president of the organization, renamed the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, which worked with the Free African Society to create Black schools and to help Black residents find jobs. Anna Coffin proudly informed her children that Franklin was a first cousin of her great-grandfather Nathan Folger. In 1827, when Quakers split into two groups—the egalitarian Hicksites and the hierarchical, Scripture-following Orthodox—Anna and her family strongly allied themselves with the most liberal of the Hicksites, whom other Philadelphians deplored.

Thomas died from typhus when Martha was eight, leaving her mother in debt. Anna, drawing on her experience as a shopkeeper and her husband’s as a trader, opened a store selling goods from East India. In 1821, at the age of twenty-six, Lucretia followed the example of Mary Coffin Starbuck, becoming a Quaker minister. She and her husband, the wool merchant James Mott, were abolitionists, but it was Lucretia whose work often took her out of town, and James who cared for their five children when she was away, with help from Anna. In Philadelphia, Lucretia and James made themselves unwelcome in polite society by socializing with anti-slavery friends, including members of the Black middle class.

As a young woman, Martha had a mischievous elfin look. Her curls escaping her bonnet, her eyes flashing, she was funny, willful, and outspoken. She had resented the strict regulations and prim teachers at her Quaker girls’ school, later commenting to Lucretia that she never saw “the little urchins creeping like snails unwillingly to school without rejoicing that I am not one of them.” Anna supplemented her income by turning the family home into a boardinghouse, and Martha, at sixteen, fell in love with one of the boarders, Peter Pelham. A thirty-seven-year-old army captain who had fought the British in the War of 1812, Pelham had lingering ailments from a bullet wound in his upper thigh. Martha found him worldly and romantic, and soon he was wooing her with poetry books by the popular British writer Oliver Goldsmith, slipping love letters between the pages.

Anna disapproved, and so did Lucretia, who was a second mother to her: Martha was too young, and Pelham was a non-Quaker, a military man, and the son of Kentucky slaveholders. Refusing to give him up, Martha married Pelham in 1826, shortly before she turned eighteen, and they moved to Fort Brooke, in the Florida territory. She described her exhilaration at living “far from the conventionalities that interfered with one’s freedom of action.” Upon receiving a letter of expulsion from Philadelphia’s Society of Friends for “marrying outside the meeting,” she tartly replied that she found the rule regrettable, and she continued to call herself a Quaker. According to the teachings of Friends, men and women were equal in the eyes of God, and everyone contained a divine spark—an “inner light.” Martha interpreted those beliefs as permission to follow her principles.

When she got pregnant, she returned to Philadelphia, and realized how much she had missed the commotion and culture of urban life—the markets, libraries and bookstores, theaters, and the lively discussions in her own family. In 1826, not long after Martha’s daughter, Marianna, was born, Peter died from complications of his war wound, leaving her a widow and a mother at nineteen. She expected to live in Philadelphia, but Anna was moving to a remote village in western New York to help a cousin run the Quaker Brier Cliff boarding school, and she insisted that Martha go with her, to earn her living by teaching writing and art. It was a joyless prospect, but Martha saw no alternative, and she and one-year-old Marianna accompanied Anna to Aurora, a village of five hundred people.

Martha’s only hope of avoiding a career as a schoolteacher was to marry again, and in 1829, she had an appealing suitor. David Wright, the son of a farmer in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and a Quaker mother who had died when he was young, was not a dashing figure like Peter Pelham, but he had a quiet sense of purpose and an open mind. Seeking professional opportunities, David found work in a law office in Aurora, while studying for the New York bar. Martha, won over by David’s solicitude, his intelligence, and his drive, married him five months later. With Martha’s savings from Pelham’s bequest and a contribution from Anna, they bought a small house and an acre of land on Cayuga Lake. David established a law practice and Martha had two more children, Eliza, in 1830, and Tallman, in 1832.

From the start, Martha found motherhood constricting. David traveled for work, a freedom that she yearned for. In a letter to him after Tallman was born, she wrote, “You complain of feeling lonely, in a crowd, surrounded by the gaieties of a city, how then do you suppose I now feel, the children all asleep, mother gone to meeting.” In the long winter months of upstate New York, one storm followed another, layering snow up to the windowsills. As it melted, the mud and slush pulled at Martha’s long skirts just as the children did, willing her back home. After going out for tea with friends, she atoned by kneeling over her washtub, scrubbing the stains from her dress and petticoats. She was only twenty-five, and could not bear the thought of being trapped in that narrow existence. In 1833, Anna moved back to Philadelphia, and Martha became listless and gloomy. David had never seen her like that, and he asked his sister to stay with him and the younger children while Martha took Marianna to Philadelphia for a few months.

They stayed with Lucretia and James, who were preparing for the first national anti-slavery convention, to be held in Philadelphia in early December. In the vibrant household of adults, the pall on Martha lifted. Lucretia was fully in her element, putting out anti-slavery pamphlets in the parlor and talking authoritatively with her white and Black visitors about the weekend of meetings and lectures. Martha helped Lucretia prepare a tea for fifty people in honor of the convention’s sharp-tongued leader, William Lloyd Garrison.

At twenty-seven, Garrison was already a figure of notoriety. He singlehandedly ran The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper in Boston. Three years earlier, he had been convicted of libel after publicly accusing a merchant from Massachusetts of being “a highway robber and murderer,” for using his ships to transport slaves. Garrison was released after serving forty-nine days of his six-month sentence, and Lucretia and James arranged for him to speak in Philadelphia. In Garrison’s talk, he attacked slavers as “man-stealers,” and argued for immediate rather than gradual emancipation—“not tomorrow or next year but today!” Lucretia was impressed with his speech, but not with his wooden speaking style. She advised him: “William, if thee expects to set forth thy cause by word of mouth, thee must lay aside thy paper and trust to the leading of the spirit.” Garrison credited Lucretia and James with inspiring him to burst “every sectarian trammel.”

Garrison regarded slaveholding as a heinous sin, and the political system as innately corrupt—starting with the Constitution, which euphemistically referred to enslaved people as “those bound to Service,” and counted each one as three fifths of a person. Insisting that Black Americans had every right to live as equals, Garrison opposed the American Colonization Society, which subsidized their resettlement in West Africa. Influenced by Quakerism and imbued with the evangelism of the Second Great Awakening, Garrison thought that God’s will, latent in each person’s conscience, needed only to be lit to spread and reform the public mind. He was a “non-resistant”—a pacifist—who called upon Americans to save their souls by finding the inner strength to renounce slavery, through the practice of “moral suasion.”

Martha met Garrison at Lucretia’s tea. Balding, pinch-faced, and bespectacled, he looked more like a censorious young parson than a dangerous dissident. Describing him to David as “the great man, the lion in the emancipation cause,” she admitted, “I had always supposed he was a coloured brother but he isn’t.” She was also surprised to learn, after Lucretia’s years of working alongside men in the abolitionist movement, that women were not invited to attend the anti-slavery convention. As an afterthought on the second day, someone was dispatched to the Motts’ house to rectify the slight. Lucretia, Anna, and the Motts’ oldest daughter rushed to the meeting.

During a discussion of the society’s manifesto, its Declaration of Sentiments, Lucretia stood up and proposed a change in one of the resolutions. “Friends, I suggest—,” she began as if she were at a Quaker meeting, but stopped when heads turned and a man gasped at her temerity. “Promiscuous” political meetings of both sexes were taboo among non-Quakers, and some delegates saw Mrs. Mott’s disruption as proof that women should have been kept from the room. The chairman, though, asked her to continue, and she suggested stronger wording, invoking the founders: “With entire confidence in the over-ruling justice of God, we plant ourselves upon the Declaration of Independence and the truths of Divine Revelation as upon the everlasting rock.” The change was made. To Martha, the sentence perfectly captured Lucretia’s sense of her own mission.

On December 5 and 6, Martha attended a few of the public talks, and she was captivated by the words of a Unitarian minister, Rev. Samuel J. May, one of the society’s co-founders. Unitarians had much in common with Quakers. They rejected the belief in a holy trinity and the doctrine of eternal damnation, preached the inherent goodness of all people and salvation through social action, and they took part in temperance, abolition, women’s rights, and other reforms. May had a kindly face and wavy whiskers that cradled a dimpled chin, but he spoke sharply about immediate, unconditional emancipation. Martha rapturously told David the speech was the most beautiful discourse she had ever heard.

Delegates at the convention resolved to organize anti-slavery societies, “if possible, in every town, city, and village in our land.” Lucretia and a dozen or so other women, white and Black, prevented from working with Garrison’s group, quickly created the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Following the lead of organizations recently formed by African American women in Salem and a group of interracial women in Boston, they invited speakers, initiated educational programs for women, and collected money for schools for Black children, disseminated petitions for immediate abolition, and held annual fairs to raise money for the abolitionist cause. The society was another revelation to Martha: women organizing across racial lines to do the same work as their male counterparts. Reverend May converted Martha to abolition; Lucretia and her friends opened her to the idea of white and Black women working together as reformers on their own.

Back at home with Marianna, Eliza, and Tallman, Martha soon saw how dangerous that kind of organizing could be. In October 1835, as members of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society made their way to a meeting they had called at their office on Washington Street, they had to push through a crowd of jeering men, who jostled them threateningly, forcing some to turn back. Inside, men lined the corridors, pelting them with insults and orange peels as they made their way into the meeting room. The women told a reporter that they had every right to advance “the holy cause of human rights.” When the mayor arrived, ordering them to go home before anyone was hurt, they reluctantly voted to reconvene at the home of one of their leaders. White men had little compunction about attacking Black women, and as the group left the building, they all linked arms, walking into a mob of several thousand men. The crowd shouted for Garrison, whom the women had invited to speak. He calmly wrote up the scene for The Liberator before escaping through an upstairs window onto a roof and into a carpenter’s shop. Discovered in the loft of the store, he was tied up and yanked toward Boston Common for a tar and feathering. His wife, Helen, saw such threats as inevitable, saying, “I think my husband will not deny his principles; I am sure my husband will never deny his principles.” The mayor and a phalanx of constables intervened, getting Garrison safely to a jail in West Boston.

Such scenes only helped to draw more women. By 1837, from Boston to Canton, Ohio, 139 female anti-slavery societies were holding local meetings and circulating petitions for abolition. That May, in New York City, Lucretia chaired the first national Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, attended by 173 women from ten states. The delegates resolved that every Christian woman in the country must do all she could, “by her voice, and her pen, and her purse,” to “overthrow the horrible system of American slavery.” Martha, who had once been aggrieved by Lucretia’s unasked-for guidance about how to live her life, now fully understood why she was considered an invincible leader. Two other women stood out: Angelina and Sarah Grimké, who had witnessed slavery firsthand. Raised by patrician parents in Charleston, South Carolina, among nine siblings and more than a dozen slaves, the Grimké sisters had renounced their heritage, moving in the 1820s to Philadelphia, where they became Quakers, abolitionists, and early women’s rights advocates.

In Angelina’s speech at the meeting, she summarily rejected the so-called separate spheres for the two sexes—an artificial set of constraints imposed by white men on middle- and upper-class white women. Men went out into the world to pursue money and influence; women cooked, cleaned, produced babies, and cultivated the attributes of piety, purity, and submissiveness. Women who voiced strong opinions or who showed any indelicate emotion, such as anger, were called vixens or shrews—or worse. Certain words were not spoken in the presence of ladies: a leg was a “limb,” hidden beneath voluminous layers of petticoats. In some households, even the “limbs” of chairs and pianos were covered in skirts, to avoid unseemly male fantasies. Women were men’s moral guardians; men were women’s overseers. At the convention, Angelina announced that every woman must refuse to accept “the circumscribed limits with which corrupt custom and a perverted application of Scripture have encircled her.” Henceforth, women would plead “the cause of the oppressed in our land” by using the one legal tool available to them—the right of the people, enunciated in the First Amendment, to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The following year, Sarah Grimké wrot...