![]()

part I into conflict

![]()

chapter 1 the understory of conflict

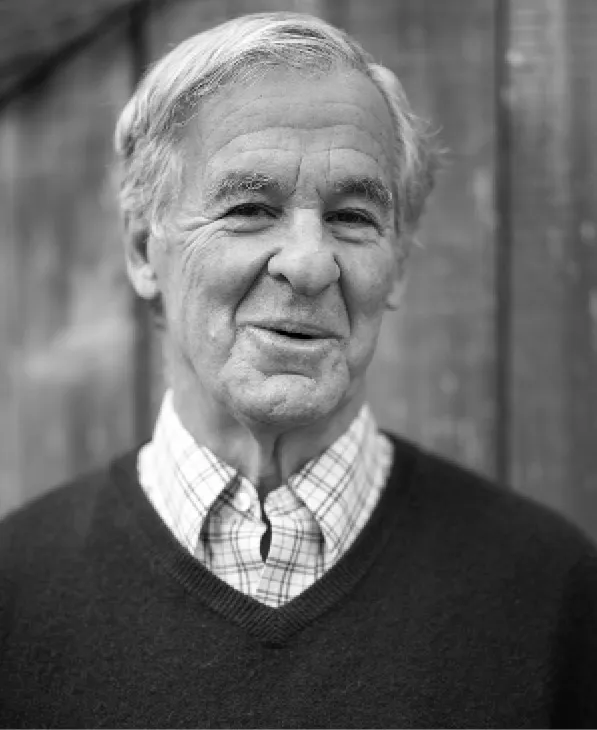

Gary Friedman. Laurie Phuong Ertley

When they asked to meet with Gary Friedman, they didn’t say why. But Jay and Lorna were old friends, so Gary invited them to come by his law office in a leafy neighborhood in Northern California. They showed up at the appointed time and told him their news: they wanted to get divorced. And they wanted Gary to help them. Both of them, at once.

Gary was stunned. Not so much by their decision to get divorced; Gary knew they had been struggling. Jay had been having an affair. They had three young children and not enough steady income. All that Gary knew already. No, what surprised him the most was that they wanted him to be their lawyer. Their only lawyer.

“I could only represent one of you,” he said gently, looking back and forth between them.

Hearing this, Lorna’s face fell. Gary tried to explain: “To try to represent you both would result in a conflict of interest.” They were dear friends but for some reason he found it hard to talk to them that way in this moment.

“Although I support your desire to keep the divorce amicable, to fully protect your interests you really are going to need separate lawyers.” The more he talked, the less he liked himself.

“Even representing one of you would be hard to do, since I’m a friend to you both.”

Lorna interrupted him. “We don’t want you to take sides. We just want you to help us make decisions. Why can’t you just help us—and not be on either side?”

The truth is, it had never occurred to Gary that he could be on both sides—or neither side. That such a thing was even possible. It was the late 1970s, and the legal profession just didn’t work that way.

“The law is much more complicated than you think,” Gary said, and he knew he was right. But something else bothered him, even as he spoke. He’d been railing against “the law” for years now. His profession was excessively adversarial, as he’d told everyone who would listen, including these same friends. He’d wanted to find a new way to practice law, one that left his clients better off. So why was he now reciting the platitudes of the profession as if he believed them?

Sitting there, Gary felt as dismayed as Jay and Lorna did. So he paused. He allowed himself to contemplate, for a moment, what they were asking. Maybe this was the chance he’d been looking for, to do something different.

“You know what?” he said. “You’re right. You should be able to do this. I want to help. I don’t know how to do it, but I’m happy to try.”

It was crazy, on its face. He had no experience doing divorces, he told them, let alone in this radical new way. But even as he issued these caveats, he saw his friends’ expressions change. They looked hopeful for the first time in a while. And he felt the same way.

For four months, the three of them worked together, in the same room. It was uncomfortable. Sometimes, it was brutal, when Jay and Lorna started yelling at each other about who got the house or custody of the children. Jay wanted more time with the kids, but Lorna didn’t want Jay’s girlfriend around them. And on and on.

It felt, at these moments, like they were caught in a vortex. Jay and Lorna hated the fact that they were fighting, but they couldn’t stop. Gary worried he was failing them. He felt like he was walking a high wire without a safety net. But it also felt liberating, in a strange way. Normally, his clients were on the outside of the arena, while he fought on their behalf, using the blunt weapons of the law. Now he was with them, accompanying them through their problems. This felt right, because they understood their own problems better than anyone. Which meant they should understand how to solve their problems better than anyone. In theory.

One day, in a pause in the bickering, Gary made a suggestion. He asked them to close their eyes and imagine their lives ten years in the future. He asked them to visualize the kind of relationship they wanted to have with their kids—and with each other—at that point. He reminded them of the time horizon. They would be in one another’s lives forever. That was just the way it was. If their daughter got married, they’d both be there. If their son had a child, they’d need to deal with each other. He traveled through time with them, and for a moment, Jay and Lorna went quiet. They were reminded that they were stuck with each other, even after the divorce. So then what?

Jay and Lorna eventually came to an agreement about the house, the kids, and everything else. And for Gary, it was proof. Proof that there was another way to do conflict, one that honored the relationships between people. He knew he had a lot to learn. But it was possible! Just because people were getting a divorce didn’t mean they had to hate each other. After they signed the papers, Jay and Lorna hugged Gary—and each other.

After that, Gary never practiced law the same way again. Hearing about Jay and Lorna’s divorce, other couples came to see him, wanting to try this thing he called “mediation.” Establishment lawyers advised their clients not to go to Gary. People came anyway. Sometimes they came because their lawyers had told them not to. He never had trouble getting clients.

People are drawn to Gary because he seems to do the impossible—tap into our best selves at our worst moments. Because as much as humans like to fight, we also want, very badly, to find peace.

High conflict makes us miserable. It is costly, in every sense. Money, blood, friendships. This is the first paradox of conflict: we are animated by conflict, and also haunted by it. We want it to end, and we want it to continue. That’s where Gary comes in.

When Gary started doing this work in the mid-1970s, the local bar association investigated him. It could not possibly be ethical for the same person to advise a husband and a wife together in the same room, or so the thinking went. But nothing came of it, and eventually, the legal profession came around to Gary’s approach. By the 1980s, the American Bar Association was hiring Gary to teach other lawyers his new way of navigating all kinds of conflicts.

the conflict trap

In the Miracle Mile district of Los Angeles, there exists a prehistoric death trap, gurgling away, right off Wilshire Boulevard, a block from an International House of Pancakes restaurant. The La Brea Tar Pits, as this place is named, can look benign, like a small, dark lake, one which bubbles up occasionally.

But scientists have found more than three million bones trapped in the depths of these pits, including well-preserved, nearly complete skeletons of massive mammals. They’ve found mammoths, sloths, and more than two thousand saber-toothed tigers. How did this happen? How did thousands of the most powerful predators on the planet all get drawn into the same small pit? And why couldn’t they get out?

The La Brea Tar Pits is a living quagmire, a place where natural asphalt has been gurgling up from the ground since the last Ice Age. What may have happened, researchers believe, is a fairly diabolical cycle: one day, tens of thousands of years ago, a large creature like an ancient bison lumbered into the Tar Pits. It quickly became stuck, hooves anchored in the sludge of asphalt, and began grunting in distress. It only took a few centimeters of the muck to immobilize a large mammal.

The bison’s alarm attracted the attention of predators like, say, the now extinct dire wolf (Canis dirus, “fearsome dog”). Dire wolves are social animals, like coyotes and humans. So a few of these wolves probably came trotting upon the scene together and, naturally, pounced on the trapped bison. What luck! Then the wolves themselves got stuck.

And so the dire wolves howled in frustration, attracting more attention. More creatures arrived. Eventually, the wolves died of hunger or other causes, and their rotting carcasses drew scavengers—some of whom also got stuck. The population of the doomed grew geometrically. A single carcass could remain visible for up to five months, attracting more unwitting victims, before finally sinking out of sight, into the murky, underwater crypt. To date, scientists have pulled the bones of four thousand dire wolves out of the Tar Pits.

In his mediation work, Gary refers to conflict as a “trap.” That’s a good description. Because conflict, once it escalates past a certain point, operates just like the La Brea Tar Pits. It draws us in, appealing to all kinds of normal and understandable needs and desires. But once we enter, we find we can’t get out. The more we flail about, braying for help, the worse the situation gets. More and more of us get pulled into the muck, without even realizing how much worse we are making our own lives.

That’s the main difference between high conflict and good conflict. It’s not usually a function of the subject of the conflict. Nor is it about the yelling or the emotion. It’s about the stagnation. In healthy conflict, there is movement. Questions get asked. Curiosity exists. There can be yelling, too. But healthy conflict leads somewhere. It feels more interesting to get to the other side than to stay in it. In high conflict, the conflict is the destination. There’s nowhere else to go.

In normal life, humans make many predictable errors of judgment. In high conflict, we make many more. It is impossible to feel curious while also feeling outraged, for example. We lose access to that part of our brain, the part that generates wonder.

High conflict degrades a full life in exchange for moments of fleeting satisfaction, and the implications are physical, measurable, and punishing. When they fight, couples experience spikes in cortisol, a stress hormone, as do political partisans after their candidate loses an election. In high conflict, cortisol injections can become recurring, impairing the immune system, degrading memory and concentration, weakening muscle tissue and bones, and accelerating the onset of disease.

Then there are all the people who do not actively participate in the high conflict, the bystanders. They are so distressed by the fight that they tune out altogether. And this category includes most people. About two thirds of Americans are fed up with political polarization and wish people would spend more time listening to one another, according to the nonpartisan organization More in Common, which labeled this group the “exhausted majority.”

And who can blame them? Most of us avoid all kinds of conflict, often for very good reason. We eventually stop hanging out with that friend who complains incessantly about his ex-wife. Or we stop reading the news. We keep our heads down. This detachment is understandable, but it leaves high conflict untreated. The extremists take over.

Overnight, high conflict can shape shift into violence, as history keeps showing us. One isolated act of bloodshed leads to collective pain on the other side, and then a need for revenge. In war, the us-versus-them mindset is an essential weapon. It is much easier to kill, enslave, or imprison people if you are convinced they are subhuman.

This was the primordial force Gary was up against, as he tried to create a new way to navigate conflict. He had successes, like the one with Lorna and Jay, but it was difficult, risky work. He had to build a new boat, a kind that could skim the surface of the Tar Pits.

Over the next four decades, Gary mediated some two thousand cases this way. He got better at it over time. He handled corporate disputes, sibling feuds, neighborhood rifts, and many other unpleasant asphalt rescues. It was not until very recently that Gary got stuck in the Tar Pits himself. He got separated from his rescue boat for a time, as we’ll see, without realizing it. And it did not go well.

Mostly, though, Gary managed to move just above the surface of the muck. He came to realize that human beings have two intrinsic capacities when it comes to solving problems: one is our capacity for adversarialism. The pursuit of mutually exclusive, selfish interests by groups working against one another. This is how the legal system traditionally operates. Husband versus wife. Prosecution versus defense.

Our other capacity, also evident throughout human history, is our instinct for solidarity. Our ability to expand the definition of us and work across differences to navigate conflicts. In fact, our evolutionary success as a species has depended more on this second capacity than the first.

During the coronavirus pandemic, billions of people responded to a highly unfamiliar, ever-changing threat with breathtaking cooperation and selflessness. Citizens around the world began staying home days before official stay-at-home orders were issued by their governments. This happened in poor countries and rich. After the U.K.’s National Health Service put out a call asking for 250,000 volunteers to run errands for at-risk people in quarantine, three times that many signed up.

There were exceptions. Specific leaders and small numbers of regular people who scapegoated others and divided the world cleanly into us and them. But for months, the vast majority of people felt a visceral pull in the opposite direction, toward collective unity. Now imagine what might have happened had more of our traditions been designed to encourage that instinct for collaboration, rather than adversarialism?

Institutions can be designed to incite either version of human nature, to provoke adversarialism or unity. But in modern times, we’ve erred on the side of adversarialism. We see everything, from politics to business to the law, as a contest between winners and losers.

And yet, Gary and other mediation pioneers proved that there is another way. They built a nonadversarial option for resolving disputes, and it usually works more efficiently and fairly than the traditional system.

Even the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized the limits of adversarialism. “For many claims, trials by adversarial contests must in time go the way of the ancient trial by battle and blood,” Chief Justice Warren Earl Burger said in his State of the Judiciary speech in 1984. “Our system is too costly, too painful, too destructive, and too ineffective for a truly civilized people.”

Couldn’t the same be said about politics today? It is too costly, painful, destructive, and ineffective for a truly civilized people.

So it made a certain kind of sense when, in 2015, one of Gary’s neighbors asked him to run for local office in his small town of Muir Beach. The Community Services District Board of Directors, as it is known, is in charge of area roads and water management. Its five members are unpaid volunteers. The board is not a particularly powerful body, and the elections are nonpartisan. But somehow, the town meetings had become adversarial and draining. People were calling each other names—just like on cable news, just like on Twitter. There had been a nasty fight recently with the U.S. Park Service over the aesthetics of a proposed new bus stop, and it had nearly torn the community apart. Couldn’t Gary, the godfather of mediation, help change the tone, and find some peace?

the michael jordan of conflict

“This is a terrible idea,” Cassidy said, for the second or maybe the t...