![]()

PART I

THE POPULIST ETHIC

![]()

1

THE “ONE-GALLUSED” CROWD ON GOVERNMENT

On July 4, 1899, more than three thousand Ozarkers descended on the town of Hardy in Sharp County, Arkansas, to take part in the local Independence Day celebration. Many folks undoubtedly enjoyed overdue visits with friends and acquaintances, some rare courting opportunities, an array of festivities and food—not to mention, for at least some, a good-sized swig or two, or nine or ten, of white lightning—and all the other activities that were customary of such Fourth of July celebrations throughout America. At the end of the day, rural families gathered around “a makeshift grandstand” for the celebration's main event, a rousing speech by Arkansas's attorney general, Jeff Davis—the “Wild Ass of the Ozarks,” as Davis's political detractors frequently called him. In firing the opening shots for his candidacy in the next gubernatorial race, Davis lamented the injustice, inequalities, and gross imbalance of power that had come to characterize Gilded Age America and Arkansas. The toiling masses were the “wealth producers” whose hands created unimaginable abundance, “but the wealth consumers are the lawmakers,” he exclaimed, who siphon off the people's riches into the hoards of a greedy few. “Under such conditions can we be free to enjoy our right to the pursuit of happiness?” Davis asked. “Do you suppose our ancestors who planted here in virgin soil the tree of liberty would recognize this country today? Would they ever have thought that the principles of this government would be so warped and distorted as to give us the miserable thing we have today?”1

The “Karl Marx for Hill Billies,” as a noted southern scholar later referred to Davis, likely drew impassioned ovations from his rural audience as he lampooned the state legislature for always bowing to the interests of railroad companies and other corporations, and when he scolded the Arkansas Supreme Court for “rul[ing] against the people” by blocking his efforts to prosecute trusts and monopolies operating within the state. Davis likewise chastised the U.S. Supreme Court for striking down the federal income tax law Congress had passed in 1894. He charged that the court's decision was a conspiracy concocted “for the benefit of aggregated wealth…[so] that the wealthy should not pay taxes on their surplus incomes, although the people said they should.” He also warned that the plan being drawn up by political elites in Little Rock to build a new statehouse was bound to become “the most infamous steal ever perpetrated against the people of Arkansas,” because the masterminds behind it were secretly scheming a shady real estate deal to benefit one of Little Rock's wealthiest families. Davis concluded this “first speech of the most memorable political campaign in the state's history” by assuring the “crowd of leathery-skinned, one-gallused dirt farmers” that he was “in this fight for the people.” “The war is on, knife to knife, hilt to hilt…between the corporations…and the people,” he later told another group of rural Arkansawyers.2

The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and Little Rock native John Gould Fletcher wrote nearly a half-century later that “it was the mountain people who had produced Jeff Davis; from the beginning of his career to its end, he was their spokesman and their champion.”3 Davis's popularity in Arkansas's upland counties, of course, did not alone account for all of his successes at the polls, but tapping hill folks’ sentiments about government and its proper role certainly played no small part in ensuring that he would never lose another election. Davis would go on to serve three terms as governor and then as a U.S. senator until his untimely death in January 1913. Despite a much stronger penchant for campaigning than policymaking, Davis's powerful political discourse embodied a Populist ethic that had come to shape rural attitudes and ideas about government during this era of sweeping social and economic change. Indeed, popular imagery of rural isolation, insularity, and parochialism belied the fact that Ozarkers stood right in the thick of Gilded Age America's social, economic, and political developments.

The popularity of Davis's rhetoric suggests that most rural white Ozarkers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, like other rural Americans “who felt trapped in an order dominated by big business” and now found “unconvincing the old gospel of laissez-faire,”4 championed progressive expansions of government power, particularly new interventions in the economy to ensure fairness and protection against the vagaries of capitalist-controlled markets. At the same time, they resisted certain arms of governmental authority that they believed unjustly catered to the “special interests” of well-to-do elites. They demanded that common working folks like themselves seize control of the public realm from privileged elites in accordance with America's democratic ideals. Contrary to popular and even scholarly assumptions about tradition-bound rural folks, most small farmers and laborers were not antimodern. In fact, most rural working people supported a forward-looking political agenda of active government that would “improve the market leverage of agriculture, to strengthen the negotiating position of labor, and to address a growing crisis of economic inequality.”5 Nevertheless, a number of rural whites’ own misunderstandings and prejudices—especially a suspicion of black Americans—worked to undercut significant potential for their mass democratic protest to deliver real change. The evolution of Jeff Davis's political career, in fact, would show that a rather vague and rhetorical “populist persuasion” could appeal, ironically, to both white country folks and town businessmen, poor dirt farmers and prosperous local elites alike, while doing little to produce much meaningful reform.6 Even so, the late-nineteenth-century rural political revolt planted a Populist ethic in the Ozarks that would serve as the lens through which most rural smallholders and working families would view their experiences with government power for the next several decades. Although typically overlooked by most historians, its Populist ethic also made many rural working folks ready to direct their defiance not only against outsiders in Washington but also more radically against well-to-do local elites who controlled the political and economic structures within the region.

Politician Jeff Davis, the “Wild Ass of the Ozarks,” with his hunting dogs, ca. 1895. Courtesy of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Arkansas Studies Institute, Little Rock.

Notwithstanding popular imagery of rural isolation and quiescence, America's emerging industrialization had created major changes in the Ozarks by the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Government—federal, state, and local—had played no small role in helping precipitate these changes. Arkansas Republicans during Reconstruction, who received some of their strongest support from mountain Unionists in certain enclaves of the western Ozarks, had subscribed to a “gospel of prosperity” and worked to employ government resources to build “a society of booming factories, bustling towns, a diversified agriculture…and abundant employment opportunities.”7 To accomplish these ends, Arkansas Republicans raised new taxes to build the state's first public and higher education systems. They created and funded the activities of Arkansas's Commission of Immigration and State Lands, which worked to attract new labor and investors by advertising the state's abundance of land—much of it free or below market prices through the federal Homestead Act of 1862 and other government programs—and other resources available to potential developers. Moreover, Republicans during Reconstruction embarked on an unprecedented number of state-sponsored infrastructure developments, especially railroad construction.8

Many of these programs helped lay foundations for new economic developments in the years ahead, but state and local Republicans’ affinity for the spoils of patronage and their frequent overextension of resources, as well as backroom deals between “ambitious entrepreneurs and unscrupulous politicians” amid their development schemes, opened them to staunch criticism, even within their own party ranks. Factionalism between the state's Republican machine and insurgent “native Arkansas Unionists”—initially led by Ozark native James Johnson of Madison County—combined with the federal government's waning commitment to Southern reconstruction to eventually open the door for conservative Democrats to regain control of the state in 1874. This new leadership promised to “redeem” Arkansas from Republicans’ “carpetbagger,” “scalawag,” and “negro” rule and, thereby, to restore a smaller government that they argued would be run by and for “the people.”9

“Redeemer” Democrats in Little Rock immediately distanced Arkansas from most forms of federal authority, in accordance with their “states’ rights” agenda. They also went to work decentralizing the state government and slashing taxes and funding for state services—policies that “would well serve the interests of the state's landed elite far into the next century,” as Arkansas historian Thomas DeBlack has written. But, as the eminent Southern historian C. Vann Woodward has noted, a “New Order” was afoot, one that ensured that government would continue playing key roles in promoting change throughout the rural South.10 Despite such “relatively laissez-faire” and more locally controlled governance, sociologists Dwight Billings and Kathleen Blee have pointed out that “the interconnections of commerce and state making” greatly shaped the changing social, economic, and political order in the Southern uplands.11

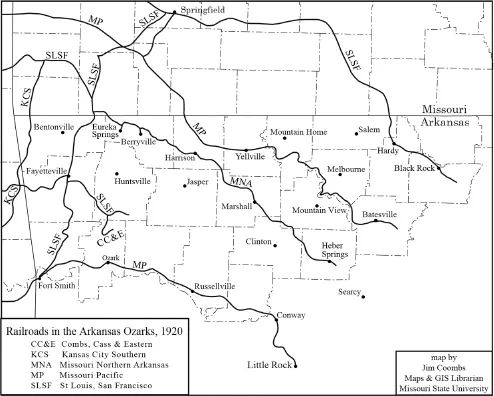

Indeed, the conservative “Redeemers” proved generally unanimous in their eagerness to promote new economic development in Arkansas. They “coveted the iron horse as the key to commercial prosperity” and issued government land grants of more than a million acres to railroad companies during the late nineteenth century. Meanwhile, they fixed low tax rates and engineered favorable property assessments as parts of special-incentives packages to lure industrial investments. Railroad construction in Arkansas rose rapidly from 256 miles of track in 1870 to more than 2,200 miles by 1900, and many more miles were added during the first two decades of the 1900s.12 Although railroad building often progressed more slowly in the rugged terrain of the Upland South, five main railroads and several subsidiary lines traversed the Ozarks by 1920.13

Major railroads in the Arkansas Ozarks by 1920. Courtesy of Jim Coombs, Missouri State University.

“Development” connected the Ozarks more fully to the national and international economy than ever and brought new market opportunities to the region. Most rural folks hoped that the cash incomes generated from these new enterprises would help them prosper and sustain their family-farm society and the relative independence it afforded. The promise seemed rich, indeed. By 1900, “the Census Bureau found more than 35,000 farms in the fifteen Ozark counties, an increase of 90 percent in just the previous two decades.”14 Increasingly, rural people committed significant parts of farm production to raising specialized cash crops and market-bound livestock, took “off-farm” work in the region's growing timber industry to supplement farm incomes, and sold mineral and timber rights to budding entrepreneurs and investors.15

Industrialization in the Ozarks, however, assumed a largely “extractive” nature, as industrialists aimed primarily to exploit the region's natural resources and cheap agricultural products and labor. Though industrialists and their regional “boosters” were fond of trumpeting their contributions to job creation and expanding economic opportunities for local populations, the lion's share of industrial profits were actually carried out of the region or were unevenly distributed to well-positioned local elites. The new economic environment provided few long-term, “value-added” improvements for local communities; much like Appalachia, the Ozarks became a “periphery region of uneven economic development.”16

Consequently, many rural folks found themselves unexpectedly frustrated and vulnerable. Some of the same opportunities that rural folks pursued as they “grasped” for yeoman independence and prosperity all too often left them marginalized amid the vagaries of market forces beyond their control. Unpredictable and speculative market prices, vicious cycles of merchant credit, exorbitant freight rates charged by railroad companies and other “middle men,” and the burdens of regressive taxation soon had many small farmers in the rural Ozarks questioning the fairness of the new economic environment.

Farm tenancy in the Arkansas Ozarks rose by nearly one-fifth during the last two decades of the nineteenth century alone. Meanwhile, a handful of prosperous merchants and larger landholders came to own more and more of the region's best farm land. But tenancy statistics and the increasing redistribution of land ownership to regional elites do not tell the full story. Backcountry farmers who managed to hang on to the deeds of their farms often did so by expanding their agricultural production onto poor and underproductive lands “previously deemed unsuitable for cultivation” and continued to fight a rearguard defense for smallholder sustainability.17 The Ozarks timber boom also provided some small hill farmers timely but only temporary relief in the form of supplemental cash incomes. However, when the timber companies finished extracting the profitable stands of timber in an area and moved on to the next, this “off-farm” income quickly disappeared. Moreover, most industrialists carried off the timber profits without investing in local communities and left behind little but a “cut-over wasteland” for struggling small farmers to try to scrape by on.18

It is no wonder, then, that rural discontentment arose forcefully in the region during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Thousands of small farmers began forming local “lodges” to discuss their common troubles and collectively demand change. The Brothers of Freedom (B of F), originally founded in rural Johnson County in 1882, emerged primarily in the region's western and central counties as one of the largest and best-organized “unions” of farmers in the Arkansas Ozarks in the 1880s. Committing themselves to the cause of common working people who were “gradually becoming oppressed,” the B of F condemned the “combinations of capital” and the big-moneyed interests “who propose not only to live on the labors of others, but to speedily amass fortunes at their expense.” Combining a “mountain-grown blend of scripture” with America's founding ideals, the organization's “Declaration of Principles” proclaimed that “God…created all men free and equal, and endowed them with certain inalienable rights, such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and that these rights are a common inheritance and should be respected by all mankind.”19

B of F organizers, led by Ozone resident Isaac McCracken, tapped into the frustrations of thousands of hill farmers and lent a new collective voice to their demands for reform. Contrary to popular portrayals of backwoods mountain folks’ reflexive suspicions of all outsiders, McCracken, the farm organization's president, was a Canadian-born “furriner” who had only recently migrated to the region. As a young boy, McCracken and his family had moved to Massachusetts, where he grew up and got his first job working on a whaling ship. After three years at sea, McCracken apprenticed himself to a machinist back in Massachusetts during the Civil War. Shortly after the war, McCracken headed to Wisconsin, where he married and started a family, and then ventured to Minnesota for a brief spell. Afterward, the McCrackens migrated to the Arkansas Ozarks to homestead a small farm in the “back-country of Johnson County.” Isaac McCracken worked primarily as a small farmer there, except for a two-year hiatus when he went to Little Rock to earn wages as a machinist. While in Little Rock, McCracken picked up some valuable labor-organizing skills as a member of the Blacksmiths’ and Machinists’ Union. Despite his outsider status, many locals in Johnson County and eventually throughout the region grew to admire and trust McCracken, who helped establish several small and independent sawmills in the area, performed dental and some other medical work in his new community, and was elected as a local justice of the peace by his backcountry neighbors. By 1885, McCracken's and other B of F organizers’ calls for small farmers to unite and “stand beside each other in the right” had succeeded in enlisting between thirty thousand and forty thousand members in western Arkansas.20

Initially, the B of F took great pains to avoid politicization and even “banned fractious political debate within its lodges.” This policy was deemed especially wise in the Ozarks, where the organization hoped to avoid competitive partisan conflicts between Democrats, Mountain Republicans, and third-party advocates. Instead, the B of F championed a “self-help” strategy that encouraged its members to essentially boycott commercial agriculture by practicing “safety-first” farming and striving toward family self-sufficiency as consumers. To obtain supplies and items they could not grow or make themselves, some local B of F lodges organized petitions that pressured some area merchants to sign contracts pledging not to charge their members more than ten percent above wholesale costs. Many others attempted to circumvent merchants and creditors altogether by forming their own local cooperatives to purchase supplies in bulk at discounted rates and to help market salable crops at better prices than farmers might otherwise obtain individually. A number of local lodges also adopted “resolution[s] to make this crop without going into debt.” “We are a set of backwoodsmen out here on this mountain and do not know any better than to take each others [sic] advice, and to help each other in the right,” declared one spokesman for a local B of F lodge. “Let the wire-pullers hold their wires and we the strings.”21

While some scholars have been tempted to see rural rebellion in the late 1800s and early 1900s as antimarket or antimodern expressions, historian Charles Postel has shown that, in fact, most small farmers and rural laborers “mobilized to put their own stamp on commercial development” and ultimately to “ensure fair access to the benefits of modernity.”22 Their primary objection to recent economic developments was to the inequality produced by industrialization and capital-...