- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

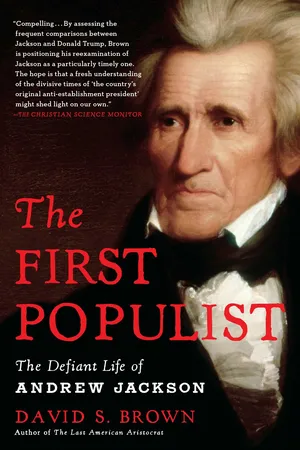

A timely, “solidly researched [and] gracefully written” (The Wall Street Journal) biography of President Andrew Jackson that offers a fresh reexamination of this charismatic figure in the context of American populism—connecting the complex man and the politician to a longer history of division, dissent, and partisanship that has come to define our current times.

Andrew Jackson rose from rural poverty in the Carolinas to become the dominant figure in American politics between Jefferson and Lincoln. His reputation, however, defies easy description. Some regard him as the symbol of a powerful democratic movement that saw early 19th-century voting rights expanded for propertyless white men. Others stress Jackson’s prominent role in removing Native American peoples from their ancestral lands, which then became the center of a thriving southern cotton kingdom worked by more than a million enslaved people.

A combative, self-defined champion of “farmers, mechanics, and laborers,” Jackson railed against East Coast elites and Virginia aristocracy, fostering a brand of democracy that struck a chord with the common man and helped catapult him into the presidency. “The General,” as he was known, was the first president to be born of humble origins, first orphan, and thus far the only former prisoner of war to occupy the office.

Drawing on a wide range of sources, The First Populist takes a fresh look at Jackson’s public career, including the pivotal Battle of New Orleans (1815) and the bitterly fought Bank War; it reveals his marriage to an already married woman and a deadly duel with a Nashville dandy, and analyzes his magnetic hold on the public imagination of the country in the decades between the War of 1812 and the Civil War.

“By assessing the frequent comparisons between Jackson and Donald Trump…the hope is that a fresh understanding of the divisive times of ‘the country’s original anti-establishment president’ might shed light on our own” (The Christian Science Monitor).

Andrew Jackson rose from rural poverty in the Carolinas to become the dominant figure in American politics between Jefferson and Lincoln. His reputation, however, defies easy description. Some regard him as the symbol of a powerful democratic movement that saw early 19th-century voting rights expanded for propertyless white men. Others stress Jackson’s prominent role in removing Native American peoples from their ancestral lands, which then became the center of a thriving southern cotton kingdom worked by more than a million enslaved people.

A combative, self-defined champion of “farmers, mechanics, and laborers,” Jackson railed against East Coast elites and Virginia aristocracy, fostering a brand of democracy that struck a chord with the common man and helped catapult him into the presidency. “The General,” as he was known, was the first president to be born of humble origins, first orphan, and thus far the only former prisoner of war to occupy the office.

Drawing on a wide range of sources, The First Populist takes a fresh look at Jackson’s public career, including the pivotal Battle of New Orleans (1815) and the bitterly fought Bank War; it reveals his marriage to an already married woman and a deadly duel with a Nashville dandy, and analyzes his magnetic hold on the public imagination of the country in the decades between the War of 1812 and the Civil War.

“By assessing the frequent comparisons between Jackson and Donald Trump…the hope is that a fresh understanding of the divisive times of ‘the country’s original anti-establishment president’ might shed light on our own” (The Christian Science Monitor).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The First Populist by David S. Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I MAN ON THE MAKE

I well recollect when I was left an orphan.Andrew Jackson, 1830

In youth, the southern-born Jackson resettled across the Appalachians, part of a larger western migration that would one day reshape the map of American politics.

1 Ulster to America

Andrew Jackson’s ancestors were part of a long Scottish migration to northern Ireland initiated by a string of English kings and queens in the company of a prolonged Tudor conquest. By the seventeenth century these established Ulster plantations mirrored a broader Elizabethan exodus to assorted Atlantic World entrepôts, including the distant forests and fisheries of North America. Many of those who came to Ulster were poverty-mired Scottish Lowlanders driven by the timeless search for better opportunities overseas. “Amongst these, Divine Providence sent over some worthy persons for birth, education and parts,” wrote one contemporary observer, “yet the most part were such as either poverty, scandalous lives, or, at the best, adventurous seeking of better accommodation, set forward that way.”1 Having made their migrations across the narrow North Channel, Jackson’s people, now Ulster Scots, lived in County Antrim, perhaps in or at least near the vicinity of Carrickfergus, one of Ireland’s oldest towns and about a dozen miles north of Belfast, then a city of some few thousand. Briefly in the 1690s, the satirist, poet, and cleric Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels, lived in neighboring Kilroot.

Jackson family lore insists that the future president’s paternal grandfather, a linen-weaver of some means named Hugh Jackson, served during the Seven Years’ War as a company officer at the 1760 Battle of Carrickfergus Castle, an imposing twelfth-century Norman structure situated on a rocky promontory. There, a detail of Ulster men, their ammunition spent, surrendered to a French raiding party of some several hundred led by the notorious privateer François Thurot—who was killed shortly afterward while contesting a stronger British squadron near the Mull of Galloway.

Jackson’s maternal side, the Hutchinsons, also resided in County Antrim, where, in about 1737, his mother, Elizabeth (Betty), was born. Little is known of her early years except that in the winter of 1759, in a modest parish church, she married Andrew Jackson Sr., thought to be the same age. Family lore maintains that Jackson, unlike his father, “was very poor” while the Hutchinsons were considered more “thrifty, industrious and capable.” Occupying a point on the Irish Enlightenment’s outer edge, Carrickfergus, older than Belfast and still somewhat medieval in outlook, long retained a reputation for countering English Anglo-Saxonism’s cold arithmetic interest in economic and imperial advancement with a Celtic superiority in matters of imagination, wonder, and folklore. “When Andrew Jackson, the elder, tilled his few hired acres,” wrote one nineteenth-century historian, the people of County Antrim “still believed in witches, fairies, brownies, wraiths, evil eyes, charms, and warning spirits. They had only just done trying people for witchcraft.”2

In 1765 Betty and Andrew Jackson were living in a thatched cottage on a small farm near Castlereagh with their two young sons Hugh and Robert; rising rents and tithes had recently aroused organized resistance by the Hearts of Oak, a regional protest movement made up largely of farmers and weavers in counties Armagh, Londonderry, Fermanagh, and Tyrone. Abandoning their tired lands that year, the Jacksons uprooted and, from Carrickfergus, sailed to America, almost certainly influenced by the earlier migration of Betty’s sisters, four of whom, between 1763 and 1766, settled just east of Appalachia along the hazy blue border separating North and South Carolina. Three of the sisters are said to have arrived unmarried but, soon after docking in Philadelphia, acquired northern Irish husbands, perhaps in Pennsylvania, possibly in Virginia, or perchance elsewhere on the primeval route down the mountains.3

Though sizable, the Scots-Irish advance into the South Carolina backwoods lagged far behind the contemporaneous (1760–1774) importation into Charleston of some forty-two thousand Africans. On the eve of the American Revolution, blacks constituted a striking 60 percent of the colony’s population.4 Years earlier, a 1731 law had taxed the introduction of newly enslaved people into South Carolina—and used a portion of the funds to encourage, through such emoluments as tools, rations, and rent-reduced lands, the relocation of Europeans. With such inducements did the colony exhibit certain racial fears that informed its course and character over time. Its Anglo founders felt vulnerable to the threat of Spanish invasion from the south, to attack from Native Americans (the recent Cherokee War, 1758–1761, fresh in memory), and to the perpetual possibility of slave insurrection (the 1739 Stono Rebellion constituting the largest ever uprising among black captives in the British mainland colonies). The settlement in which Andrew Jackson would spend his formative years, in other words, idled apprehensively, alive to the suggestion of conspiracy and willing to spill blood to quell its enemies.

The Jacksons were part of a significant circa 1760s exodus out of northern Ireland; one estimate claims that as many as twenty thousand Ulsterites left the province during this crucial decade. In fair weather these voyages might take seven or eight weeks and be attended by a host of discomforts and privations associated with eighteenth-century ocean travel. Just where the Jacksons made landfall is still something of a mystery. The General’s first biographers, John Reid and John Henry Eaton, both associates of their subject and perhaps deferring to his supposition, insisted that the family arrived in Charleston. In the 1930s, however, the historian Marquis James dissented, writing, “Had the Jacksons landed at Charleston at any time between 1761 and 1775 their debarkation would have been noted in the records of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, which are intact in the original manuscript in the office of the Historical Commission of South Carolina at Columbia.” James thought Philadelphia, a principal designation of Scots-Irish settlers, a far likelier guess.5 But in 2001 biographer Hendrik Booraem argued otherwise:

James’s reasoning no longer seems as good as it once did. Part of his argument was that the Crawfords [the family of one of Betty Jackson’s sisters] resided in Pennsylvania before coming to the Waxhaws [a region on the North and South Carolina border], and that Andrew and Betty Jackson probably came with them; but… current understanding of the Crawfords’ migration suggests that they… could as easily have come [from Ireland to America] via Charleston as via Pennsylvania. James’s other point, that the Jacksons’ and Crawfords’ names would have appeared in Council Records if they had entered through Charleston, is based on a misunderstanding. The Council Records list only immigrants who were applying for bounty land; those who intended to buy their own would not have registered with the Council. Accordingly, I have accepted the Reid version.6

In a 2017 communication to the author, Booraem added: “My thinking was that Andrew and Betty Jackson knew where they were going, because other kinfolk had arrived in Carolina before them, so it made more sense for them to go directly to Charleston and skip the long overland trek from Philadelphia; and the colony of South Carolina had the welcome mat out for Irish settlers at that time, because they were trying to build up the population of the backcountry.” Booraem does allow, however, that “there is no hard evidence where the Jacksons landed in America.”7

With more certainty we know that the family settled in the Waxhaws region, named after a meandering tributary creek of the Catawba River once home to the Waxhaw tribe, who were defeated in 1716 by the Catawba, who were themselves devastated by smallpox in 1759. Down to perhaps a few hundred, they remained in the area during Jackson’s youth, “harmless and friendly,” reduced to vying for a living in the woven basket and trinket trades.8 Betty and Andrew moved onto a large allotment of land, perhaps as much as two hundred acres, adjoining Twelve Mile Creek and in the vicinity of Betty’s sisters and their families. The farm, only indifferently surveyed, sat about four miles from the nearest post road; its remoteness proposed an availability born of thin, unpromising soil. It is possible that the Jacksons, at this time apparently without a deed, squatted on the land, a by no means uncommon occurrence. In any case, Betty, Andrew, and their two boys, survivors of the long journey from Ulster to America, set about building a new life.

In the late winter of 1767, the Jacksons appeared to be making progress; the family ate garden crops grown in fields laboriously claimed from the forest, and they sheltered in a small log cabin. Then suddenly, perhaps in early March, Andrew Jackson Sr. died. Legend suggests that he collapsed while attempting to maneuver a particularly heavy log, though it seems just as likely that the incident implicated a broader exhaustion from which his broken body, engaged in constant labor, failed to recover. He took to bed, never to rise again. Conveyed by a primitive wagon to the Waxhaw churchyard, he received burial, with no marker, then or since, to indicate his remains. Part product and part victim of an unforgiving colonial frontier, the senior Jackson later became a small but central piece in the elaborate lore of his rising son. “It is a delightful reflection to the emigrant from the European monarchies,” wrote a florid biographer, “that, like the father of Andrew Jackson, he may, under the institutions whose protection he seeks, give a chief magistrate to a great nation, and live in history more honoured than the fathers of kings.”9

The elder Andrew, whether more honored or not, never saw his third, last, and namesake son, born March 15, 1767. Newly widowed, Betty and her boys eventually stayed with the family of Betty’s sister Jane Crawford. The McCamies, the family of yet another Hutchinson sister, Peggy, and her husband, George, were only about a mile away—but in a different colony. Jackson believed that he was born at the Crawford homestead in South Carolina, though there is an oral tradition passed down by Jackson’s cousin Sarah Leslie, who insisted that she attended the delivery at the McCamies’ in North Carolina. To this day both states claim Jackson’s nativity in statues and markers. Though the evidence remains inconclusive, those in the Palmetto State point with pride to an 1824 communication in which Jackson wrote: “I was born in So Carolina, as I have been told, at the plantation whereon James Crawford lived about one mile from the Carolina road.” Jackson’s will left a legatee “the large silver vase presented to me by the ladies of Charleston, South Carolina, my native State.”10

Over the next fourteen years, young Andrew lived at the Crawfords’ with his mother. As a poor relation Betty took up many of the household chores and, along with caring for her sons, looked over no fewer than eight Crawford children. She eventually sent her eldest, Hugh (Huey), to live with the childless McCamies; the evidence places him under ten at the time. A strong, portly, and pious woman, Betty wanted her youngest boy educated and groomed to become a Presbyterian minister. If not quite cut out for the cloth, Jackson seemed nevertheless eager to keep this maternal presence nearby throughout his life. His wife, Rachel, also a strong, portly, and pious woman, inclined in her later decades to a dry and partial Presbyterianism. In such echoes and linkages it is perhaps permissible to surmise that more than any Jackson, Crawford, or McCamie man, Betty proved to be Andrew’s most important influence. Her strong sense of honor apparently anticipated his own. “One of the last injunctions given me by her,” he told a friend, “was never to institute a suit for assault and battery, or for defamation [as the defamed should defend their own rights]; never to wound the feelings of others, nor suffer my own to be outraged; these were her words of admonition to me; I remember them well, and have never failed to respect them.”11 Possibly in such stern maternal instruction lie the seeds of several duels and lesser dustups.

Described by one contemporary as “mischievous” and prone to pranks, Jackson enjoyed in youth physical activity, competition, and self-assertion. “He was exceedingly fond of running foot-races, of leaping the bar, and jumping; and in such sports he was excelled by no one of his years,” wrote biographer James Parton, who interviewed many of Jackson’s Waxhaws neighbors:

To younger boys, who never questioned his mastery, he was a generous protector; there was nothing he would not do to defend them. His equals and superiors found him self-willed, somewhat overbearing, easily offended, very irascible, and, upon the whole, “difficult to get along with.” One of them said, many years after, in the heat of controversy, that of all the boys he had ever known, Andrew Jackson was the only bully who was not also a coward.12

Unlike his brothers, who attended common schools, Jackson, presumably earmarked for some distant Presbyterian pulpit, received more formal training. Later in life, when contesting for political power, he heard repeatedly dismissive references to his shaky education. One 1824 newspaper, touting the supposed virtues of a John Quincy Adams–Andrew Jackson presidential ticket, played upon the conjectured contrasts in the men, asking readers to imagine a perfect pairing of:

John Quincy Adams,Who can write,And Andrew Jackson,Who can fight.13

Certainly Jackson’s rickety syntax (when compared to previous presidents’, not to the average American’s) gives some surface credibility to this claim, but on the whole it is a false lead. As an adult Jackson read with interest a good number of newspapers, journals, letters, and law books; he left behind a sizable library and maintained an extensive correspondence. But it is true, and particularly in youth, that he valued the outdoor life—hunting and riding—and likely found few bookish models among his many cousins. Nothing if not resourceful, Jackson always read enough to get by, trusting his instincts above all else.

And yet because of Betty’s expectation that her youngest enter the ministry, she and the Crawfords set aside money for Jackson to attend local academies. In these frontier establishments, run by Dr. William Humphries and James White Stephenson, the boy acquired the rudiments of a formal education, learning his letters and how to read. Engaged in practical training, he never developed an interest in either literature or poetry, and with the possible exception of The Vicar of Wakefield—a hugely popular moral tale written in the early 1760s by Oliver Goldsmith and featuring comedy, satire, and sentimentalism—novels meant little to Jackson. It is perhaps enough to say that his mind worked quickly, intuitively, and fluently. Singled out by Betty for an education denied his brothers, Jackson possibly evinced a conspicuous mental spark, a persuasive tongue (the sermonizer’s imperative instrument), or a spontaneous intelligence. He may have simply struck his mother as special.

Considering Betty’s strong presence in her youngest son’s life, it would be easy if imprecise to disregard her absent husband’s influence. From testimony we know that the junior Andrew, something of a rowdy and a ruffian, could be bossy, oppressive, and high-handed. He exhibited further a tremendous confidence that often bordered on conceit. Bearing in mind his secondary status living in the Crawford household, his lack of a strong paternal figure, and his lowly rank among a scrum of older brothers and cousins, it is possible that the fatherless Jackson dealt with insecurity by both asserting and overasserting himself. He soon learned that a strong personality brought him attention and recognition; he seemed to relish opportunities to compete and proclaim his strength. “I could throw him three times out of four,” one classmate reported, “but he would never stay throwed. He was dead game, even then, and never would give up.”14

2 Forged in War

Nothing quite impacted Jackson like the American Revolution. It destroyed his patriot family, left him an orphan, and shifted his loyalties decisively and forever from clan to country. Just sixteen when the war concluded, Jackson saw service as a courier in the militia, attended to troops at the Battle of Hanging Rock fought in the chaotic South Carolina interior, and was later captured and held prison...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Introduction: The Populist Persuasion

- Part I: Man on the Make

- Part II: Hero for an Age

- Part III: Warrior Politics

- Part IV: King of the Commons

- Part V: A World of Enemies

- Part VI: Center of the Storm

- Part VII: Southern Sympathies

- Part VIII: Winter’s Wages

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Index

- Illustration Credits

- Copyright