eBook - ePub

Rites of Retaliation

Civilization, Soldiers, and Campaigns in the American Civil War

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate politicians, military commanders, everyday soldiers, and civilians claimed their approach to the conflict was civilized, in keeping with centuries of military tradition meant to restrain violence and preserve national honor. One hallmark of civilized warfare was a highly ritualized approach to retaliation. This ritual provided a forum to accuse the enemy of excessive behavior, to negotiate redress according to the laws of war, and to appeal to the judgment of other civilized nations. As the war progressed, Northerners and Southerners feared they were losing their essential identity as civilized, and the attention to retaliation grew more intense. When Black soldiers joined the Union army in campaigns in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, raiding plantations and liberating enslaved people, Confederates argued the war had become a servile insurrection. And when Confederates massacred Black troops after battle, killed white Union foragers after capture, and used prisoners of war as human shields, Federals thought their enemy raised the black flag and embraced savagery.

Blending military and cultural history, Lorien Foote’s rich and insightful book sheds light on how Americans fought over what it meant to be civilized and who should be extended the protections of a civilized world.

Blending military and cultural history, Lorien Foote’s rich and insightful book sheds light on how Americans fought over what it meant to be civilized and who should be extended the protections of a civilized world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rites of Retaliation by Lorien Foote in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de la Guerra de Secesión. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

FELONS AND OUTLAWS

Maj. Gen. David Hunter was an oddity. He was a regular officer from the old army with a West Point education, and he was an abolitionist. The two usually did not go together. In 1856, the army had posted Hunter to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, where free-soil settlers were at war with the radical pro-slavery expansionists of Missouri. What he saw there convinced him that slavery caused the Civil War and that emancipation was necessary to defeat rebels against the U.S. government. If given a major command, he wrote Republican senator Lyman Trumbull on December 9, 1861, “I would advance south, proclaiming the negro free and arming him as I go. The Great God of the Universe has determined that this is the only way in which this war is to be ended, and the sooner it is done the better.” In March 1862, the U.S. War Department sent the sixty-year-old to command the Department of the South at Hilton Head, South Carolina, where the Union navy and army in November 1861 had captured a set of coastal islands and the 10,000 slaves who lived there. U.S. Treasury Department agents and Northern philanthropists controlled the plantations and organized free labor and educational experiments there. Hunter had a grand strategic vision for victory in his department: arm slaves on the islands; send them on raids using the rivers of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida; use the raids to liberate slaves and destroy the resources of slaveholding rebels; and arm the liberated slaves to conduct more raids.1

Robert Gould Shaw, on the other hand, fit the mold of young men from his Boston Brahmin social class. His parents were wealthy radical abolitionists with kinship ties to New England’s mercantile and industrial elites. Like his multitude of cousins, he had traveled extensively in Europe, attended Harvard, pursued parties and pleasure more than his studies, questioned whether he shared his parents’ commitment to reform, and fought depression as he struggled to find a profession. Four days after Abraham Lincoln called for troops to suppress the rebellion, the twenty-four-year-old volunteered to serve. He wanted to do his duty to defend the honor of the United States. After a brief stint as a private in a New York militia unit, he received a commission, as a second lieutenant, in the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. Shaw’s attitudes mirrored those of the other gentleman officers in his regiment. He believed slavery was bad, rebellion was even worse, educated men should lead, and lower-class soldiers needed the hard hand of discipline to keep them in line. He wrote lengthy letters to his parents from the 2nd’s camp in northern Virginia.2

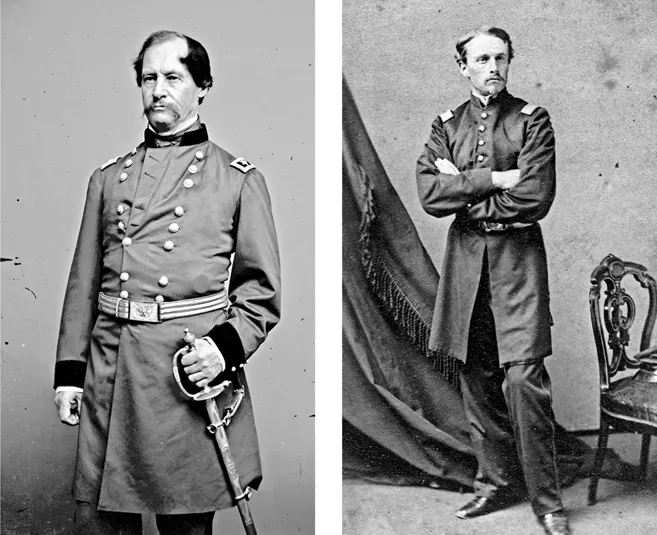

Despite their differences, Shaw and Hunter had something important in common. By the end of the summer of 1862, the Confederacy declared Shaw to be a felon and outlawed Hunter in a sweeping retaliation proclamation designed to enforce President Jefferson Davis’s interpretation of civilized war on the Union armies operating in South Carolina and Virginia. The wartime military actions of Hunter and Shaw uncovered the deepest fears that white Americans on both sides of the battle lines shared. Being a civilized person in a civilized nation was an important part of their identities. The wartime behavior of white enlisted men in Virginia and the decision of a rogue Union commander to recruit Black men to fight in South Carolina defied many white Americans’ understanding of themselves as civilized people. Retaliation against Shaw and Hunter would determine whether Americans were what they claimed, able to control the darkest passions of men and to civilize the “barbarians” in their midst.

Hunter acted on his strategic vision within two months of arriving at Hilton Head. The Union had early momentum in the symbolically important campaign against Charleston, the city that birthed the secession movement. Confederate forces fired the opening shots of the war from Charleston on April 12, 1861, when their artillery forced the surrender of the United States garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Three weeks later, the USS Niagara inaugurated a naval blockade. The presence of this screw steamer was a symbolic gesture, since the single vessel could not hope to close the three different channels that gave ships access to the port of Charleston. Military action began in earnest on November 7, 1861, when a Union fleet of seventy ships under the command of Samuel DuPont attacked Port Royal, located fifty-two miles southwest of Charleston and thirty-two miles northeast of Savannah. It was one of the best natural harbors along the south Atlantic coast, and the Union hoped to gain a coaling and supply station for a legitimate blockade of Charleston. The Union vessels moved in an elliptical pattern as their guns took turns pounding the defending forts. Confederate forces evacuated and Union troops under Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Sherman took possession of the island. DuPont achieved the Union’s first major victory of the war. The U.S. Navy possessed a base for the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron and for army incursions along the coastline of three Southern states.3

Maj. Gen. David Hunter, outlaw, and 2nd Lt. Robert Gould Shaw, felon, according to Jefferson Davis’s August 1862 retaliation proclamation. Hunter and Shaw actually had very different interpretations of civilized conduct in war and of the role of Black troops. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The Union victory at Port Royal had drastic social consequences disproportionate to the minor number of troops involved. White families fled the surrounding islands, abandoning plantations and 10,000 slaves to the occupying Federal forces. Plantation owners in the South Carolina low country as far inland as thirty miles from the coast evacuated thousands of slaves to the central and up-country regions of the Carolinas. The Union occupiers transformed the Sea Islands into experimental communities with no parallel in the history of the antebellum South. Two days after entering Port Royal, Sherman appointed a superintendent of contrabands who organized local African Americans into a workforce that unloaded supplies and navigated naval vessels. Through the First Confiscation Act of August 1861, Congress had authorized agents of the Federal government to seize property, including slaves, which had been used to support insurrection. The luxury cotton grown in the Sea Islands offered an opportunity for the government to make a profit, so Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase sent a Treasury agent to collect the cotton crop and plan for production on the abandoned plantations in 1862. He also sent Edward L. Pierce, a young anti-slavery Massachusetts attorney, to investigate the condition of the Black people and develop a plan for them. Robert Gould Shaw’s father, Francis George Shaw, helped form the National Freedmen’s Relief Association in order to fund and recruit labor superintendents and teachers for the plantations.4

When Hunter arrived on the scene, he saw the Black men in his department as a pool of soldiers rather than a source of labor. This revolutionary view challenged most white Northerners’ assumptions about the place of Black people in civilization. They believed that enslaved men and women were not fully civilized, because they lacked the historical traditions, formal education, and higher culture necessary to participate in republican government. Hunter’s predecessor held this perspective. In his general orders organizing Black labor on the abandoned plantations, Sherman appealed to Northern philanthropists to come to his department. He wanted teachers “until the blacks become capable themselves of thinking and acting judiciously.” New England volunteers would teach Black people on the islands “the rudiments of civilization … their amenability to the laws of both God and man, their relations to each other as social beings.” Northerners like Sherman thought it would take decades at minimum to incorporate Blacks fully into civilization.5

Hunter agreed that formerly enslaved Black people were ignorant and degraded. He differed in his belief that the military itself was an effective training tool of civilization. “The discipline of military life will be the very safest and quickest school in which these enfranchised bondsmen can be elevated to the level of our higher intelligence and cultivation,” he publicly announced. “Their enrollment in regular military organizations, and the giving them in this manner a legitimate vent to their natural desire to prove themselves worthy of freedom, cannot fail to have the further good effect of rendering less likely mere servile insurrection, unrestrained by the comities and usages of civilized warfare.”6

When he arrived at Port Royal, Hunter moved quickly. One of his critics within the army remarked that Hunter was “dreamy by habit & efficient in spasms.” If so, then Hunter had one of his spasms in May 1862. On May 6, he began organizing military companies of Black men from the islands. He sent James Cashman, a local Black man, to enlist 100 men from St. Helena Island. He appointed Brooklyn bricklayer, firefighter, and Methodist class leader Charles T. Trowbridge to captain the first company of recruits. And he sent a message to the Treasury’s labor superintendents in charge of the abandoned plantations asking them to tell the former slaves about military service and taking down the names of any volunteers.7

Three days later, Hunter issued an order emancipating all the enslaved men and women in the Department of the South, comprising South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Because those three states had “taken up arms against the United States,” he had declared martial law on April 25. “Slavery and martial law in a free country are altogether incompatible,” General Orders No. 11 proclaimed on May 9. “The persons in these three states, heretofore held as slaves, are therefore declared forever free.” When the number of volunteers for the military companies failed to meet Hunter’s expectations, he ordered all able-bodied Black males between the ages of eighteen and forty-five to Hilton Head. On May 12, what one New England teacher on Port Royal called “the black day,” he sent to the plantations squads of Union soldiers who rounded up terrified Black men at gunpoint and shot a handful who resisted. The Hunter companies went into camp at Hilton Head and began to drill.8

Charles T. Trowbridge, 1st South Carolina. Trowbridge captained the first company of recruits in Hunter’s Regiment and in the 1st South Carolina. He was in constant command of armed Black soldiers from May 9, 1862, to February 9, 1866. (From S. Taylor, Black Woman’s Civil War Memoirs, 46)

Hunter’s conscription ran roughshod over the goals and desires of the Black men and women living on the coastal islands, who wanted the freedom to determine their own futures. He also alienated Treasury officials and Northern philanthropists, who wanted to produce a lucrative cotton crop and prove the capabilities of Black people to work under a free labor system and who had invested time and Federal resources organizing work on the plantations. Hunter assumed that Black men wanted to fight for their freedom; indeed, he believed that only by fighting for their freedom would they deserve it. However, attorney Pierce wrote Hunter that the Black men on the plantations did not want to be soldiers. They did not yet know whether they could trust Union officials, and their main goal was to preserve and protect their families in a time of chaos and flux.9

When the white Union soldiers arrived on Mrs. Jenkins’s plantation on St. Helena Island to take away the able-bodied men, several Black women gathered with axes in their hands but eventually set them aside and said good-bye to their husbands and sons with the “wildest expressions of grief.” The Northern superintendent of the plantation wrote Hunter that one woman said that “she had lost all of her children and friends, and now her husband was taken and she must die uncared for.” All expressed their belief that this was a “final separation” of their families. The Black leader of the people on another plantation reminded Union officials that their master had told them that the Union army would sell them to Cuba and suggested that this forced conscription was similar enough to the master’s threats. “This rude separation of husband and wife, children and parents, must needs remind them of what we have always stigmatized as the worst feature of slavery,” one Treasury official on St. Helena Island lamented.10

Hunter acted without the permission or sanction of the Lincoln administration and without consulting its other representatives in the Department of the South. After Hunter issued the conscription order, Pierce told him that he was “thwarting a plan of the Government.” Hunter replied, “He could not help it if two plans of the Government conflicted.” The major general was being disingenuous, since the War Department was not aware of his orders until after he issued them.11

Lincoln publicly disavowed Hunter’s actions, issuing a proclamation on May 19 voiding General Orders No. 11. “Government of the United States had no knowledge, information, or belief of an intention on the part of General Hunter to issue such a proclamation,” Lincoln declared, “nor has it yet any authentic information that the document is genuine.” The president carefully worded the rest of the proclamation. He hinted that as commander in chief of the army and navy he might have the power to declare slaves in a state free if it were a “necessity indispensable to the maintenance of the government” but that any such power belonged to the president and not to the “decision of commanders in the field.” Lincoln reiterated the official policy of his administration, a promise of federal financial aid to any state that adopted a plan to abolish slavery gradually, and appealed to the people of the slaveholding states to accept the offer.12

Although Lincoln retracted the order and publicly chastised Hunter, his administration was shifting its policy regarding slavery in the spring of 1862. The desire to suppress the rebellion was trumping fears that Blacks did not belong in a civilized war, especially among Republicans who believed that all human beings shared equal natural rights to liberty. Republicans in Congress and Northern governors who advocated emancipation as a moral imperative or as a weapon of war increased their pressure on the president after Hunter’s order. When Secretary of War Edwin Stanton wrote Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew asking the state to supply three or four more infantry regiments, Andrew responded on May 19 that his people would be reluctant to step forward under current administration policy. “But if the President will sustain Hunter, recognize all men, even black men, as legally capable of that loyalty the blacks are willing to manifest, and let them fight, with God and human nature on their side, the roads will swarm, if need be, with multitudes whom New England would pour out to obey your call,” he wrote.13

Hunter, for his part, ignored Lincoln’s rebuke and moved forward with his plans. He wrote Stanton on May 31 to request steamers and additional troops for operations against Charleston, Savannah, and Jacksonville, Florida. He intended to occupy the entire south Atlantic coast. “The slaves would flock into our posts, and the enemy be thus injured as much as in any other way,” he wrote. “According to my experience they would rather lose one of their children than a good negro.” Stanton authorized Hunter on June 9 to move against Charleston with the troops already under his command.14 Operations against the city were already underway when Hunter received Stanton’s telegram.

Hunter and Admiral DuPont made this first serious attempt to capture Charleston after Robert Smalls, a Black pilot on a Confederate steamer, brought the vessel to the Union fleet on May 13 and conveyed important intelligence. Confederate troops had abandoned a fort at the mouth of the Stono River, which offered the Union a beachhead on James Island, where Confederates had amassed infantry and built significant fortifications to defend both the land and water approaches to the city. On May 21, DuPont sent gunboats up the Stono that fired on Confederate cavalry who were helping panicked planters remove their slaves. This action opened the way for hundreds of slaves to cross into Union lines. On June 2, two divisions of Union soldiers landed on James Island and built a fortified camp at Grimball’s Plantation.15

The Confederate position on James Island contained five miles of earthworks and the superbly constructed Tower Battery, located near the village of Secessionville. The battery had four faces configured in a giant M shape and seven guns mounted on parapets up to sixteen feet high. Marshes surrounded the works so that the only approach for attacking troops was a stret...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures & Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. The Ritual of Retaliation

- 1. Felons and Outlaws

- 2. Servile Insurrection

- 3. Prisoners

- 4. Massacre

- 5. Human Shields

- 6. Pillagers and Assassins

- Conclusion. The Crisis of Civilization

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index