![]()

1 Armies

I can’t offer you either honours or wages; I offer you hunger, thirst, forced marches, battles and death. Anyone who loves his country, follow me.

—Garibaldi

Few people could be neutral about Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. Both loved and reviled, the “Young Napoleon”—as admirers dubbed him—curiously combined strengths and weaknesses. A superb organizer but cautious fighter, McClellan earned the respect, admiration, and especially affection of countless officers and enlisted men. Yet he was nothing if not deliberate, and he readily produced reams of excuses for inaction. His obsessive secretiveness raised questions about his willingness to fight and even about his loyalty. At once arrogant and insecure, he treated his military and civilian superiors with condescension and occasionally contempt.

McClellan regularly and all too indiscreetly questioned the military and political judgment of President Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and Gen. in Chief Henry W. Halleck. McClellan favored a war of maneuver with limited objectives, fought by conventional rules, and even tried to protect civilian property. Whatever his private views on slavery, he opposed forcible emancipation. Nor did he discourage national Democratic leaders from using him as a cat’s-paw against the Lincoln administration. A man of deeply conservative instincts, McClellan sometimes saw himself as God’s appointed agent in the war, and with a conviction bordering on megalomania, he fully believed that the fate of the Union rested in his hands. This egotistic confidence, however, failed to mask deep fears about supposed enemies, whether real, potential, or imaginary.

President Abraham Lincoln and Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan meet after Antietam (Library of Congress)

Had he not saved the Army of the Potomac after the retreat from the Virginia Peninsula and John Pope’s debacle at Second Bull Run? And had not his victory at Antietam been a great masterpiece and a vindication of his generalship? Unfortunately Robert E. Lee’s army had escaped destruction; Lincoln and his advisers failed to recognize McClellan’s genius. Halleck and Stanton had refused to provide the needed men and supplies. Worse, they had plotted to poison the president’s mind against him.

As the warm days of early fall 1862 passed quickly with the Army of the Potomac still immobile, Lincoln abandoned his gingerly approach to the touchy McClellan. “You remember my speaking to you of what I called your over-cautiousness,” the president wrote on October 13. “Are you not over-cautious when you assume that you can not do what the enemy is constantly doing? Should you not claim to be at least his equal in prowess, and act upon the claim?” Attack the Rebels’ communications, the president urged. Strike at Lee’s army. Obviously irritated, Lincoln closed his letter with a flippant remark that surely enraged McClellan: “It is all easy if our troops march as well as the enemy; and it is unmanly to say they can not do it.”1

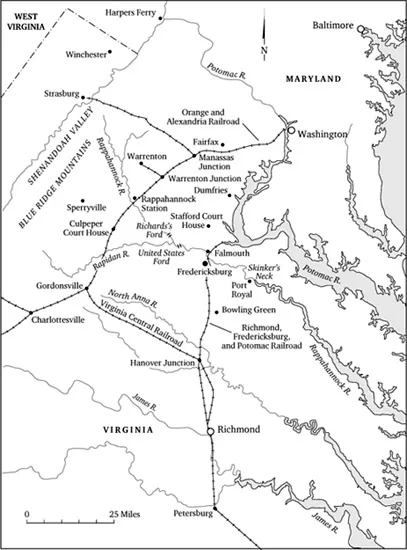

At last prodded to action, on October 26, 1862, McClellan got the Army of the Potomac moving. He required eight days to bring his troops across the Potomac on pontoon bridges and march twenty miles into Virginia. With supply routes established along the Orange and Alexandria and Manassas Gap railroads, McClellan meandered toward Warrenton. Heartened, Lincoln nevertheless fretted over the slow pace. For his part the general was sulking. A sarcastic inquiry from the president about the state of his cavalry horses had made him “mad as a ‘march hare.’” McClellan told his wife, Ellen, “It was one of those dirty little flings that I can’t get used to when they are not merited.” Although more men were still needed to fill depleted regiments, he informed Lincoln that he would “push forward as rapidly as possible to endeavor to meet the enemy.” But even as McClellan advanced, he kept one eye fixed on his enemies in Washington. “If you could know the mean & dirty character of the dispatches I receive you would boil over with anger,” he informed Ellen. His customary martyr’s pose degenerated into outright scorn for his superiors: “But the good of the country requires me to submit to all this from men whom I know to be greatly my inferiors socially, intellectually & morally! There never was a truer epithet applied to a certain individual than that of the ‘Gorilla.’” McClellan railed against Halleck, vowed to “crush” Stanton, sparred with Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery Meigs, and argued with Herman Haupt over rail transportation. Yet at least for a few days at the beginning of November he sounded confident to both his wife and the president.2

Many of the troops shared his confidence. The sight of such a magnificent force on the move especially impressed the exuberant new recruits, not yet ground down by the hardships of marches, the dullness of camp, or the horrors of combat. “God is on our side,” averred a pious Hoosier, “and now I believe that the movement is taking place which . . . will terminate this unholy rebellion.”3 The men’s letters reported great progress and predicted imminent triumph. The Rebel capital appeared to be within reach, and a New York private offered to “give many a good day’s rations to be present at the taking of Richmond.”4

Delays and defeats had not seriously dampened the army’s spirits, nor had the naïveté of the early war been entirely knocked out of the soldiers. But after more than a year’s hard fighting, it had become clear, at least to most veterans, that victory would not come easily or cheaply. Even men who believed the current campaign would be decisive did not sound that sanguine. “I expect a hard fight,” Lt. Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain of the 20th Maine admitted, because the Confederates “are admirably handled & fight with desperation.” A New York surgeon agreed that “Blood must flow” before the rebellion was finally defeated.5 Fearful of carnage yet cautiously hopeful, the Army of the Potomac nonetheless got caught up in the excitement of a campaign that apparently offered such promise of success.

So did the northern public. As the march began, newspapers carried

Theater of operations

glowing reports of McClellan’s advance into Virginia. Sensational dispatches had erroneously predicted certain victory before, but once again the press whipped up enthusiasm for the latest “On to Richmond.” Echoing confident soldiers, editors claimed that the Rebel capital would be in Union hands by the new year. This campaign, declared the conservative Boston Post, should silence McClellan’s radical Republican critics once and for all. Ironically, the much abused commander of the Army of the Potomac had broader political support than even his Democratic friends recognized. Moderate Republican editors also issued cheerful bulletins and praised McClellan’s generalship. Perhaps this time the results would match the buildup.6

Such wishful thinking, however, hardly prepared anyone for a winter campaign, and because McClellan had squandered so many beautiful fall days after Antietam, this new drive against the Rebels began ominously late in the year. The rigors of life in the field during early November doused the Pollyannas with a bracing shower of reality. The weather grew colder each day. When orders got confused and footsore regiments took wrong turns, the prolonged exposure only elicited louder complaints. After a day trudging through mud and finding a key bridge had been burned by the Confederates, the men of the 11th New Hampshire finally settled into camp around midnight. “Cold enough to freeze an Icelander,” groaned Willard Templeton as the men huddled around fires with the wind blowing rain into their faces. During this “toughening,” as surgeon Daniel Holt termed it, many men fell ill, and some died.7

On November 7, in the Federal camps stretching from Snicker’s Gap toward Warrenton, a winter storm left four inches of sleet and snow on the ground. The next morning at White Plains, Elisha Hunt Rhodes of the 2nd Rhode Island shook the snow off his blanket and almost decided not to write in his diary. He did, however, express one half-frozen, sardonic wish: “How I would like to have one of those ‘On to Richmond’ fellows out here with us in the snow.”8 Keeping warm, especially at night, proved nearly impossible. After sleeping on the cold ground, a young New Hampshire private declared himself “completely used up and so tired and stiff that I could scarcely walk.” Even with roaring fires the most ingenious soldiers could keep only half their bodies from freezing at any given time. Nor could they avoid the acrid smoke from wet wood. Stoics burrowed into their overcoats and kept their feet near the fires.9

Fortunate regiments bedded down in two-man shelter tents. Propped up with sticks or muskets with a pole across the top, they measured a little more than five feet long and a little less than five feet wide. One Rhode Islander thought a shelter tent afforded hardly more room than a “good sized doghouse”; a Pennsylvanian dismissed it as a mere “pocket handkerchief.” More reflective soldiers, however, felt thankful for not being among the many who slept with an unimpeded view of the heavens. Besides, a good fire could make those drafty tents feel luxurious on a chilly night.10

Soldiers humorously recounted their sufferings in letters and especially in memoirs; many prided themselves on surviving the ordeal. In words echoed by scores of other men, New Yorker James Post concluded, “It’s really astonishing how much the human system can endure,” but he still asked his wife to send some “thick” underwear immediately. Although much better supplied than their opponents, the soldiers in the Army of the Potomac occasionally suffered from clothing shortages, especially when Rebel cavalry raided supply trains. Some Federals also went barefoot. As the 131st Pennsylvania approached Middleburg, Virginia, the soles fell off Howard Helman’s shoes, exposing his feet to sharp stones. The new boots he received that evening badly pinched during the next day’s march. Even fellows with decent shoes developed painful blisters.11

Infrequent washing helped wear out clothes. Underwear, pants, shirts, and jackets appeared dingy and quickly became ragged. Lice thrived amidst the filth, and fighting them was a constant, largely unsuccessful battle. For soldiers accustomed to the standards of middle-class cleanliness, filthy, vermin-infested clothing symbolized how much the war had changed daily life and undermined civilized values.12

Complaints about lice and ragged clothing, however, paled beside the grumbling over short rations. Soldiers could endure almost anything so long as they had enough to eat, but even the well-provisioned Army of the Potomac could not keep the men adequately fed during marches. Supply wagons fell behind, became mired in mud, or got lost on country roads. Veterans knew enough to eat heartily before a march began; along the way, men wolfed down rations and then went hungry later. Newly enlisted regiments learned these lessons through hard experience. Men in the 24th Michigan began shouting “Bread! Bread!” whenever they saw high-ranking officers.13

Food was not just important; it was an obsession. Meals were described to the last detail, including the exact number of hardtack consumed. Roughly three inches square, these “crackers” were a staple of the military diet and certainly well named because they could break teeth unless soaked in pork grease or crumbled into coffee. Camp wags held that they were best consumed in the dark so the worms or weevils crawling out would escape notice. After grinding down his back teeth on hardtack, young Robert Carter declared that it “wasn’t fit for hogs.”14 A few crackers and some raw salt pork could hardly satisfy a soldier in a cold camp at the end of a long day’s march.

Regiments, however, occasionally lacked even the hardtack and the pork. Sometimes only roasted corn and a cup of coffee stood for breakfast, while corn kernels scrounged from the mules made a poor dinner. The cooking utensils alone might turn the stomach of the hungriest soldiers. “A dirty, smoke-and-grease begrimed tin plate and tin dipper have to serve as the entire culinary department,” John Haley of the 17th Maine noted.15 But the soldiers and their clothes were no cleaner than the plates or cups, and if the food would not bear close inspection, no wonder some worried that the war might turn a generation of young men into barbarians unfit for home life.

Such musings assumed, however, that the beloved soldier boys would survive the war, and even though McClellan committed his precious troops to combat slowly, sparingly, and reluctantly, this hardly ensured their well-being. The greatest threat to the Army of the Potomac—or any other Civil War army—came not from the hard marches or even enemy bullets. The physical demands of the campaign—the cold, the cheerless bivouacs, the worn-out shoes, and the poor food—made them vulnerable to an insidious, deadly foe: disease. For many soldiers the greatest shock of army life was watching comrades fall, not on blood-soaked battlefields but in camps and hospitals to unexpected enemies such as typhoid or dysentery or even childhood maladies.16 As the weather grew colder in early November, a few soldiers bravely claimed that outdoor living was toughening them up, but in reality the exposure took a heavy toll. Each morning, stiff with rheumatism, men arose for the day’s march after a night punctuated by nagging coughs. Hungry soldiers allowed their stomachs to overrule their brains and devoured sutlers’ pies, overpriced, indigestible, and almost sure to cause diarrhea.17

Unfortunately the common camp diseases, many of which were aggravated by poor sanitation and badly cooked food, followed men on the march. The rates of typhoid fever remained nearly as high as they had been during the pestilent summer months on the Virginia Peninsula. The incidence of dysentery and diarrhea (the latter undoubtedly a much underreported malady) had fallen considerably, though the mortality rate was rising. Diarrhea struck without warning and often defied treatment. A New York private dosed himself with laudanum and stayed in his tent, but a week later he sampled some cider and “loosened up my bowels again.” As McClellan’s march began, the 11th New Hampshire left camp without Sewall Tilton. The poor man had suffered from diarrhea for five weeks. His weight had fallen and his hands trembled so much that he could barely write. More than a month later, weaker yet, he was seeking a discharge from the army.18

If you could be here, a Connecticut soldier advised his mother, “and see the poor fellows dying around you, worn out by marches and disease and see the misery brought upon us by this awful war, then you would be still more anxious to have the war ended.” Each day men saw friends from home, boys in their own company, and complete strangers buried along the roads or in camp. Hospitals in Maryland and northern Virginia and around Washington were full. Disease thinned the ranks of the most robust regiments and reduced others to skeletons. On October 29 Sgt. George S. Gove recalled in his diary how the 5th New Hampshire had left Concord a year earlier more than 1,000 men strong but now could muster only about 200 fit for duty.19 Ever present death and the fear of whom it would strike next depressed even the strongest soldiers.

Somehow being tossed into a hastily dug hole, what passed for burial with “military honors,” ...