![]()

1

The Yi Peoples

In the millennium that preceded the rise of the first Chinese empire about 1600 B.C., the diverse Yi1 (and Yue) peoples of eastern and southern China developed quite independently from the Neolithic tribes centered in the Yellow River valley in north China. Separated by mountains that run parallel to the south China coast, the inland peoples spoke a Tibeto-Burman language most closely related to modern Chinese, whereas the eastern and southern Yi peoples are believed to be linked linguistically to the future Khmers and to the Austronesians who would spread throughout the Pacific and Indian Ocean basins. In the stew of Neolithic cultures from which Chinese civilization would evolve, the Yi had a strong influence.

The inland people were tied to the soil; the Yi, pressed against coastal mountains, were forced to turn to the sea for their livelihood. Thus, the seafaring tradition of China begins with the Yi.

At the height of the last ice age, fifty thousand years ago, the continental shelf of Asia was exposed, linking mainland China with Taiwan and the Malay Peninsula with Sumatra, Borneo, and Java. The forefathers of the Yi peoples were believed to have migrated2 down from the highlands of central China to the broad shoreline of this exposed shelf. In bamboo rafts, some crossed the narrow body of water, then no more than thirty-five or forty miles wide, from the island of Sulawesi to New Guinea and eventually onto Australia, where their descendants settled on the shores of an enormous inland sea.

These migrants are believed to be the world’s first “boat people,” that is, the first people to cross a body of water and settle a new land. Crete was not colonized from the mainland of Greece until about 8,000 B.C., more than forty thousand years after Australia.

Although Australia’s inland sea dried up long ago, geologists exploring the ancient dunes of the Willandra Lakes in the late 1960s literally stumbled across the bones of Australia’s first-known inhabitants, which simply appeared one day in the shifting sands. Hundreds of settlement sites around the old seabed in western New South Wales have since been identified, indicating that a community of more than three hundred thousand people had flourished there. Examining the skulls of the Willandra Lakes people, the scientists discovered they bore a striking resemblance to skulls of Neolithic people in China’s Yangzi River valley thousands of miles to the north. Both were thin and delicate and contemporary-looking in every respect—thus a link between these distant people was first suspected. Recent genetic studies confirm3 that native Melanesians, Australians, and New Guineans are, in fact, descended mainly from southeast Asians, and, despite appearances to the contrary, bear a closer genetic relationship to them than to Africans.

While southern Asians were moving into Indonesia and Australia, Asians north of the Yangzi River migrated across the then-dry Bering Strait into Alaska and North America. Both early migrations may well have been precipitated by a dramatic shift in the course of the Yangzi River itself. Although the question has not been studied extensively, some geologists believe that at some time during the last ice age, the collision of continental plates that produced the Himalayas also caused tremendous rifting in the Yunnan plateau, which forced the Yangzi to flow from its source in the Tibetan mountains due east into the South China Sea, instead of following its original path south to the Gulf of Tonkin. It was as if the Mississippi had suddenly turned and flowed into the Atlantic instead of the Gulf of Mexico. Such a cataclysmic geological event4 certainly disrupted life in central China, sending early man on a quest for a stable environment and food source, even if it meant, in the case of the southern Asians, venturing out across an unknown sea.

In time, the glaciers melted and the seas rose, setting off another series of migrations.5 From 14,000 B.C. to 4000 B.C., a hundred-mile strip of coast off south China was submerged as the sea achieved its current level. Never in recent geological history had the seas risen so fast. The coastal inhabitants were forced to contend with swamped land and rapidly submerging river valleys. Eventually, it is believed, they took to the sea again in large numbers. This second wave of wayward southern Asians became the ancestors of the great seafaring peoples of Indonesia and Polynesia.

In about 9000 B.C., it has been estimated, people from the mainland of Asia crossed the Formosa Strait and settled Taiwan. Then, from 7000 to 5500 B.C., they moved from Taiwan to the Philippines and later, around 4000 B.C., on to the Malay Peninsula and the Moluccas and east to the Bismarck Archipelago. By 1300 B.C. they reached Fiji.

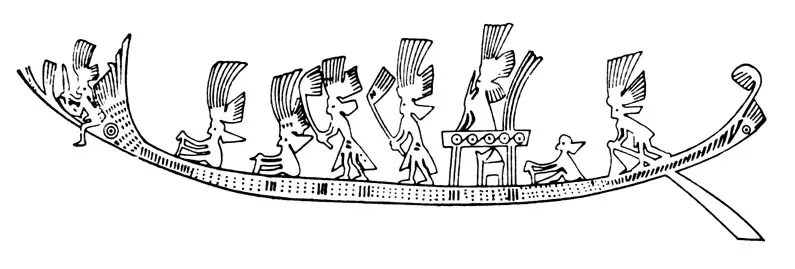

From at least the seventh or sixth century B.C., if not earlier, Southeast Asians began to etch pictures of long canoes on the sides of sculpted, barrel-shaped drums. A trail of buried bronze drums6 has been found from northern Laos and southwestern China to Sulawesi in Indonesia. The etchings depict canoes with cabins or raised platforms and exotic bird’s-head ornaments adorning the prows. The canoes also appear to have been steered by large oars or sweeps. The actual boats of the early Pacific seafarers undoubtedly bore some resemblance to the drum pictures.

As time went on and these seafarers ventured farther and farther from the Asian mainland,7 sails, outriggers, rudders, and other control devices were added to the canoes and rafts to make them more seaworthy and maneuverable. Indonesia, particularly the central island of Sulawesi, became a hub for the design and construction of oceangoing vessels, and the two terms used throughout Oceania for “boat,” waka (or vaka) and paepae (or pahi)8 are thought to have a connection to early Chinese words for boats.

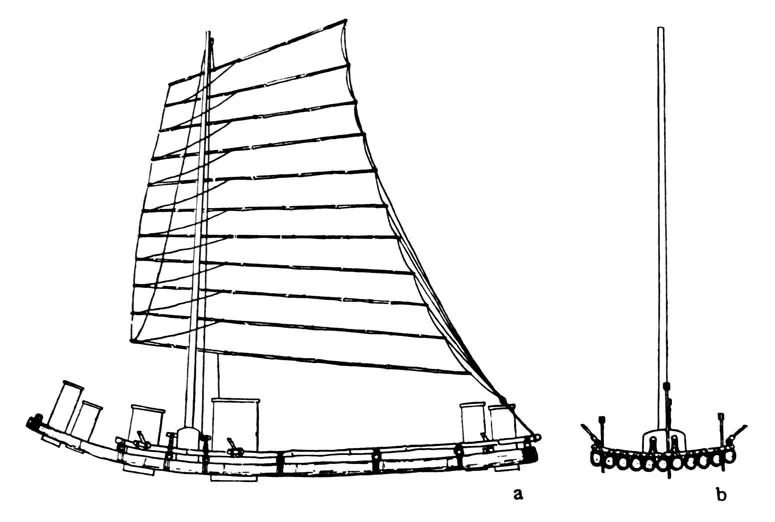

The seamanship of the early Southeast Asians was so remarkable that they were able to cross the six-thousand-mile expanse of the Indian Ocean to settle Madagascar9 off the east African coast. There are also strong indications that they sailed in the opposite direction and successfully crossed the Pacific, landing in Central and South America. This was believed to be the first period of contact between Asia and the New World. The vessels that made this extraordinary voyage are believed to be identical to the sailing rafts10 still used today by fishermen off the coasts of Taiwan, Vietnam, and Peru. They are made of tightly bound balsa logs and employ a complicated steering system that allows them to be maneuvered across the trade winds. Six leeboards or centerboards, three in the stem and three in the bow, can be adjusted to steer a course close to the wind, regardless of the direction or strength of the wind.

Pacific sailing rafts were believed to have carried Asians to Central and South America in the first millennium B.C. (Courtesy of The Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan.)

Spanish explorers who arrived in South America in the sixteenth century reported seeing many of these rafts, which were then in extensive use. They marveled at large versions with enclosed cabins that could accommodate a hundred people. Others were fitted with many masts and could skim the surface of the waves like catamarans, ferrying goods up and down the coast faster, they said, than their own single-hulled sailing vessels.

Vestiges of the early contact between Asia and the Americas can also be found in the remarkably similiar traditions of bark-cloth making11 found between two isolated tribes on opposite sides of the Pacific. The upland people of Sulawesi and the Otomi tribes in the central Mexican highlands are both skilled cloth makers. Although styles of bark beaters vary greatly among native peoples around the world, these two tribes use nearly identical beaters—flat stones with crosshatched patterns mounted on flexible cane handles that look like miniature tennis rackets. And, of the seventy separate steps involved in the production of Mexican cloth, fifty are the same in Sulawesi.

Otomi women cut down whole branches from trees, instead of just stripping off the bark. They felt pieces of bark together instead of sewing them, which is easier, and they like to decorate their bark cloth with the sticky gum from rubber plants. They do these things for no other reason than that they have always done them this way. And (although they don’t know it) it was also the way Sulawesi women worked. The chances of such complex traditions and tools evolving independently halfway around the world seem remote.

What first drove early Indonesian people to attempt the long journey across the Pacific is unclear. Sitting on the rim of the Pacific plate, the Malay Archipelago is one of the most volatile volcanic regions of the world, however, and violent eruptions may well have precipitated periodic mass exoduses from the islands in the first or second millennia B.C.

While the Indonesians perfected their sailing rafts and commenced their epic voyages, the maritime traditions of the Yi of Shandong and northern Jiangsu, also called “Dong Yi” or Eastern Yi, were gradually being incorporated with inland cultures, giving birth in 1500 B.C. to the Shang, the first historic “Chinese” kingdom. The Shang rulers established authority over a two- to three-hundred-mile area in the central Yellow River valley. They had chariots, a complex writing system, and sophisticated bronze technology. Priest-kings were guided in the conduct of their daily affairs by divination from cracked sheep bones, and, perhaps influenced by the Yi, the priests also began to use large quantities of turtle shells from south China in their rituals. From the Eastern Yi, the Shang also acquired wet-rice agriculture, irrigation, lacquerware, bamboo, bark cloth, and longboats. The Shang shared the Eastern Yi’s reverence for jade and their skill in carving it.

The Shang flourished for five hundred years, until, in about 1045 B.C., a western people, the Zhou, drove them from their cities in the fertile Yellow River valley with a ruthlessness that would come to characterize all changes of power in China. Those Shang not killed in the conquest were subject to harsh military control by the Zhou or were forced to abandon their homes. It is thought that some of these displaced Shang12 might have turned to the coastal Yi on the periphery of the empire and taken to the sea in their boats.

A later legend13 associated with the southern coastal people relates the tale of a brother and sister who took refuge in a wooden drum during a flood. The drum floated in the turbulent waters, and, when the flood subsided, an eagle plucked up the two and set them down on dry land. Since there was no food on the flood-ravaged land, the pair offered their own flesh to the eagle in gratitude. They finally survived the trial by planting seeds they had managed to bring with them in the drum. In the myth, the drum is the protector into whose shelter the pair unquestioningly delivered themselves. The legend perhaps symbolizes the blind faith that early Asian seafarers had in their own “wooden drums”—their boats—which enabled them to risk long journeys into the unknown.

Decorative pattern of a voyaging canoe on a Han dynasty bronze drum.

Mysteriously and unexpectedly, out of primitive societies without highly developed arts, two highly sophisticated civilizations took root in the New World as the Shang empire was crumbling. Nothing seems to be able to account for the sudden ability of the Chavin craftsmen14 of Peru to fashion stylized bronze figurines of jaguars—which bear, coincidentally, an astonishing resemblance to late Shang miniature statues of tigers. Like the Shang pieces, the Chavin feline forms have projecting teeth, and an intricate pattern covers their bodies. They have distinctive rings on their tails that are realistic for Asian tigers—but are not found on South American jaguars or pumas. A similar coincidence occurred at about the same time in Mexico, where Olmec artists displayed an extraordinary skill in fashioning jade15 that appears to have had no precedent in local crafts. Like the Shang, the Olmec used jade as burial offerings in tombs, where it seems to have performed some protective or preservative function.

While stressing the originality of early American cultures, most scholars are generally agreed that there appears to have been at least some Asian influence in the New World before the arrival of Columbus.16 How much influence and exactly when this influence occurred are the subjects of much debate, but one of the most likely moments of contact seems to be around 1000 B.C. and may have involved the displaced Shang and their Yi boatmen.

By 221 B.C. a local ruler in western China succeeded in defeating the last of the eastern states and created the first unified empire in China...