![]()

Sea Power: The Surrender of Worldwide Supremacy

It depends upon what you count to know exactly what your position is.

—Arthur Balfour, House of Commons, 1896

On 6 December 1904, Lord Selborne, first lord of the Admiralty, put before the cabinet a memorandum marked “Distribution of the Fleet (Very Confidential).”1 In opening his report Selborne declared:

A new and definite stage has been reached in that evolution of the modern steam navy which has been going on for the last thirty years, and that stage is marked not only by changes in the materiel of the British navy itself but also by changes in the strategic position all over the world arising out of the development of foreign navies.2

To the west, “the United States are forming a navy the power and size of which will be limited only by the amount of money which the American people choose to spend on it.” To the east, “the smaller but modern navy of Japan has been put to the test and has not been found wanting.” Closer to home the Russian fleet had been increased; the navies of Italy, Austria-Hungary, and France were strong, especially in the Mediterranean; and a “new German navy” had come into existence.3

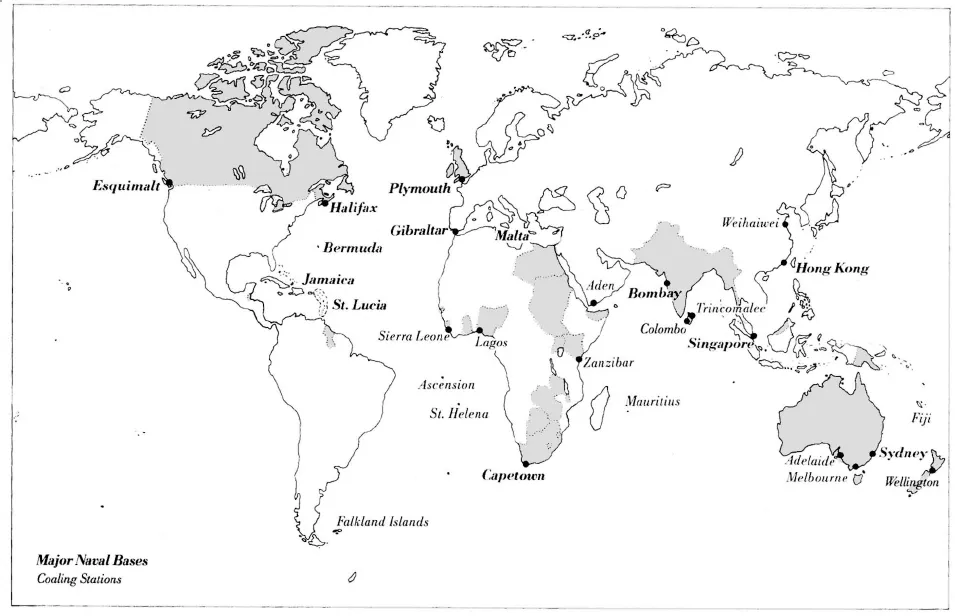

British Naval Facilities, 1900

In the face of all this the British navy was distributed on the basis of principles that dated “from a period when the electric telegraph did not exist and when wind was the motive power.”4 Its squadrons were scattered at stations at the four corners of the earth, and many of them included slow, poorly armed, aged vessels that, in the event of war, could “neither fight nor run away.” The time had come to eliminate these useless ships and to group those remaining in a peacetime pattern that would also be the “best strategical distribution for war.”5

Selborne’s memo called for the worldwide reorganization of Britain’s naval forces. New Channel, Atlantic, and Mediterranean fleets were created (with home ports at Dover, Gibraltar, and Malta, respectively) and the battleship component of the first two was increased at the expense of the third. Meanwhile, the squadrons cruising in distant waters were consolidated and reduced in strength. The Pacific, South Atlantic, North American, and West Indian squadrons were withdrawn, and a Cape squadron was created to take on some of their duties as well as to patrol the west coast of Africa. In Asia an “Eastern warfleet” centered at Singapore was organized out of the Australian, Chinese, and East Indian stations. Both of these flotillas had their numbers “ruthlessly reduced” by the weeding out of old and inefficient vessels.6

The intention and eventual result of the scheme that Selborne announced was to permit a permanent strengthening of British naval power in European waters at the expense of the Far East and the Western Hemisphere. This became evident in the following year as five battleships were withdrawn from the China station and assigned to the Channel fleet.7 In February of 1905 the first lord also announced cutbacks in Britain’s dockyards at Halifax, Esquimalt, Jamaica, and Trincomalee.8

Looking back, it seems obvious that the changes announced in late 1904 marked a significant shift in the strategic posture of the British Empire. In the three hundred years that followed the defeat of the Spanish Armada, England’s trade and her catalog of overseas possessions had grown enormously. The security of Britain’s empire, its commerce, and its shores depended on an ability to control the world’s oceans. English vessels had to be able to transit safely between the center of the empire, off Europe’s shores, and any one of dozens of destinations at the periphery from Alexandria to Bombay, from Capetown to Halifax.

From the close of the Napoleonic Wars the British navy was able to achieve its objective by maintaining superiority in the “narrow seas” around Europe. Until the latter part of the nineteenth century there were no naval competitors outside the Continent, and the European powers were able to devote only sporadic attention to naval development. By blockading enemy fleets in their home ports and by attacking them as they attempted to pass through the confined waters of the English Channel, the North Sea, the Suez Canal, and the mouth of the Mediterranean, British warships could control access to the world’s oceans. Writing in 1943, Harold and Margaret Sprout described the situation in these words:

Through its hold on four narrow seas . . . Great Britain could virtually dictate the terms of Europe’s access to the “outer world.” Under conditions prevailing until near the end of the nineteenth century, control of these four narrow seas had political and military effects felt around the globe. As long as no important center of naval power existed outside Europe, England’s grip on the ocean portals of that Continent constituted in effect a global command of the seas.9

During the fifteen years leading up to the period of this study, the fortuitous circumstances on which Britain’s worldwide sea supremacy depended had begun to change. In Europe, America, and the Far East new naval powers arose and old ones strengthened their fleets. Between 1895 and 1905 British statesmen were forced to reconsider the assumptions on which the entire empire had been built. By the end of that ten-year period, Britain had acquiesed in the loss of its longstanding control of the world’s oceans. Instead of trying to dominate everywhere, the British navy was now directed more narrowly toward retaining its superiority in the waters close to home. Instead of relying only on its own resources to secure the safety of its shipping and empire, Britain was now forced to depend on the continued cooperation of foreign powers. In another fifteen years Britain’s navy would just be equal to that of the United States. In twenty-five, England would be the second-ranked naval power.10

All this is plain from a vantage point of eighty years. Yet, as Margaret Sprout has noted, the implications of what occurred at the turn of the century “are clearer in retrospect . . . than they were in prospect.”11 Indeed, on first inspection the transition from global to merely local supremacy would appear to have been accomplished with a minimum of turmoil and debate. Is it possible that Britain’s leaders did not realize the importance of what was occurring? How did they think about sea power? How did they assess their diminishing ability to control the use of the earth’s “great highway”? And what did they think they could do about it?

Background

Discussion of Britain’s naval position, official and unofficial, public and private, was shaped around the presence of two deceptively simple and seemingly complementary ideas. These two notions, “command of the seas” and the “Two Power Standard,” represented different ways of thinking about sea power. The first involved a functional measure of capability (of what might today be called “outputs” or “outcomes”), and the second involved a straightforward numerical comparison of forces (or “resources”). Where these concepts came from and how they came to be fused together is the first part of this chapter’s story. How they became separated at the close of the century, what that separation meant and the confusion it caused, will be the second.

“Command of the Seas”—The Ideology of Sea Power

Historian Paul Kennedy has written that “if there was any period in history when Britannia could have been said to have ruled the waves, then it was in the sixty or so years following the final defeat of Napoleon.”12 Supremacy is seldom conducive to hard thinking. It comes as no surprise, then, that for much of the nineteenth century little intellectual energy was expended in analyzing or justifying Britain’s position at sea. The importance of England’s continuing preeminence was accepted more as a fact of life than as the result of adherence to any abstract theory.13

This is not to say that no one thought or wrote about sea power during these years, but much of what did appear amounted to little more than reheated tales of wartime derring-do.14 Nevertheless, there was what might be called an “inarticulate navalism” that found expression in the periodic utterances of politicians and Admiralty officials. In these it is possible to discern the seeds of something that would later grow into a more fully elaborated form.

The existence of Britain’s far-flung empire and (for those who were unenthusiastic about that institution) the growing volume of its overseas trade (and especially, from midcentury on, its dependence on imported food) brought home to all but the most obtuse the sea’s inescapable importance. The fact that British soil could be reached only by crossing water provided a final proof, for those who required one. There was thus an agreed need for naval supremacy, and demanding it or affirming it was a pastime that, in the words of one author, “could unite the ‘economical monomaniacs,’ Richard Cobden and Joseph Hume, with Palmerston and Canning.”15

The precise form of British maritime superiority remained a matter open to discussion. Some commentators concluded that Britain would have to maintain powerful fleets wherever its interests lay, in other words, on all the oceans of the world. Thus Sir James Graham, first lord of the Admiralty between 1830 and 1834, told Parliament that “if the Britis...