- 289 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

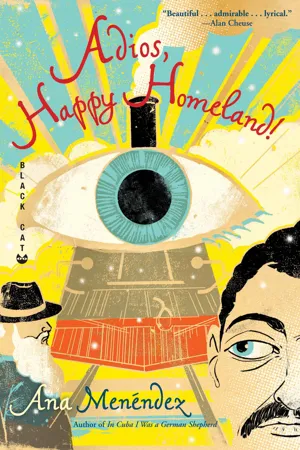

Adios, Happy Homeland

About this book

From the award–winning author of

In Cuba I was a German Shepherd, short stories

with a magical and modern take on the idea of migration and flight.

Adios, Happy Homeland! is a collection of interlinked tales that challenge our preconceptions of storytelling. It examines the life of the Cuban writer, deconstructing and reassembling the myths that define her culture. It blends illusion with reality and explores themes of art, family, language, superstition, and the overwhelming need to escape—from the island, from memory, from stereotype, and, ultimately, from the self.

We're taken into a sick man's fever dream as he waits for a train beneath a strange night sky, into a community of parachute makers facing the end in a windy town that no longer exists, and onto a Cuban beach where the body of a boy last seen on a boat bound for America turns out to be a giant jellyfish.

With Adios, Happy Homeland!, Menéndez puts a contemporary twist on the troubled history of Cuba and offers a wry and poignant perspective on the conundrum of cultural displacement.

Adios, Happy Homeland! is a collection of interlinked tales that challenge our preconceptions of storytelling. It examines the life of the Cuban writer, deconstructing and reassembling the myths that define her culture. It blends illusion with reality and explores themes of art, family, language, superstition, and the overwhelming need to escape—from the island, from memory, from stereotype, and, ultimately, from the self.

We're taken into a sick man's fever dream as he waits for a train beneath a strange night sky, into a community of parachute makers facing the end in a windy town that no longer exists, and onto a Cuban beach where the body of a boy last seen on a boat bound for America turns out to be a giant jellyfish.

With Adios, Happy Homeland!, Menéndez puts a contemporary twist on the troubled history of Cuba and offers a wry and poignant perspective on the conundrum of cultural displacement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adios, Happy Homeland by Ana Menéndez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Littérature générale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Parachute Maker

BY OVID RODRIGUES

In the foothills of the mighty Sierra, facing the great bay of Cienfuegos, in the little village of Aquilo (now erased from the maps), there once lived a modest maker of parachutes. He was a lover of adjectives, and a bit long-winded, but otherwise lived simply and quietly in his thatched-roof hut.

The parachute maker, whose name was Belafonte, was born in Aquilo, as were his father and his grandfather before him. It was the same story on his mother’s side, though maternal lineage is not usually recorded this way. In short, Belafonte’s family had never known any other place but Aquilo.

For as long as anyone could remember, the village had been isolated from the rest of Cuba. Some people said this was because outsiders attributed a terrible temper and strange powers to the people of Aquilo. It may be true that others believed the calumny—Cubans are well known for their superstitions—but it was nevertheless nonsense, the typical kind of story that city people like to spin about country people. In fact, the people of Aquilo were just like other people. What was different was the weather. Aquilo sat at the particular convergence of several phenomena that were unexplained at the time but which we now understand as being primarily caused by a foehn, a wind capable of quickly raising temperatures by adiabatic compression (it is well known for its ability to induce bad moods as well as melt ice cream cones in two seconds flat). This wind, generated by the mountain slope directly behind Aquilo, contributed to cyclogenic conditions whose causes and effects would require several pages of graphs and equations to explain. For our purposes here, it suffices to say that Aquilo was always windy. In fact, wind was such a constant in Aquilo that there was no word for “windy,” windiness being the normal condition. Similarly, there was no word for “calm” either, as the villagers had no experience of windless days. What the people of Aquilo did have was several variations—up to two hundred thirteen, by some counts—on the word “viento” that included designations for a caressing wind (“terciopielago”); a strong, temperate wind that came down the mountains in the early evening (“barbadeboreas”); a hot, steady wind (“horniento”); and a very, very hot foehn that changed direction at noon and blew up the mountain (“liber-notus”).

Like many ancient peoples, the villagers of Aquilo worshipped the wind (whom they called Aquilo the Great), which provided them with electricity (every home naturally had a windmill) and a reliable constant in their lives. It should be no surprise to the student of evolutionary biology to learn that the Aquilinos had, over the years, adapted both physically and mentally to the reality of their windy village. The typical Aquilino face was flat across the cheekbones, with eyes narrowed into a permanent squint. The hair was always worn short. The people’s mood—when not affected by the foehn—was particularly breezy and light. They farmed and tended goats. The women made popovers. And they did all this with uncommon swiftness. But it should be no surprise that for their main livelihood, the Aquilinos had chosen to make parachutes. It’s not clear how the industry first arrived in Aquilo. Some said it had been developed by a native Aquilino, Esteban Bañes, who got the idea for building a parachute as he watched a plastic bag caught in the updraft of a strong horniento. Historians, who have never appreciated the value of a good anachronism, dispute this account, as well as many others in this story. They contend that parachutes had been brought to Aquilo by a stranger named Stefan Banic, who spoke a bizarre language. According to this version, Stefan remained in the village for a few years until he was finally made mad by the foehn and either vanished into the air or returned home. But Stefan (or Esteban) left behind his aerodynamic secrets, and by the time of the wars, the villagers were doing a brisk business in parachute making or, to use the more appropriate expression, envelope design. As the global economy developed and distant countries fought one another for dominance, more and more of the great powers found themselves outsourcing envelope production to Aquilo. So the village flourished, buoyed by the wings of history. Or something like that.

All would have been well, except that Aquilo, aside from the wind, was no different from any other village anywhere else in the world. It had its farmers and its merchants, its workers as well as its bosses. And not everyone was good. In those years, two things were indispensable to the craft of parachute making. One was silk; the other was the sewing machine. Now, the silk distributor was an honest and affable fellow named Mauricio. He bought his fabric wholesale in the capital, had it transported by mules to Aquilo, and sold it at a profit that was neither austere nor predatory. Like many honest men, Mauricio delighted in pleasing others. So he would often go out of his way to arrange for a particular color or a special weave. This especially endeared him to Belafonte, who was rapidly becoming known as Aquilo’s master envelope maker. While all the villagers could turn out good parachutes, Belafonte’s work was on another level: magnificent creations that today would be hanging in museums as works of art.

Unfortunately, Seraphim, the agent for the sewing machines, was neither honest nor beloved. He had managed to get an exclusive contract for the distribution of the machines, and he marked them up so high that they became unaffordable. As a consequence, Aquilinos were forced to lease the sewing machines on something called layaway, paying a few pesos each month to essentially rent the machines, which they knew they would never come to own. Then, as now, the world market for sewing machines was dominated by a single North American firm. Its English name could be mispronounced in Spanish in such a way as to render it unacceptably vulgar. So the product of this particular North American company was known as Cantante in Aquilo and, in spite of the beautiful creations it produced, its song was ultimately a sad one. Every few years, Belafonte would talk about traveling overseas himself and appealing to the makers of Cantante in person, but nothing came of these threats. Overseas trips were expensive and stressful, and after a few days of storm and bluster, Belafonte would calm down and resume his work, which was one of the few things that brought him joy.

Rumors of the Aquilinos’ discontent naturally reached Seraphim. But his riches put him beyond such cares. Alone among the villagers, Seraphim did not work as a parachute maker, the wealth from his distribution deal being so great as to nearly overwhelm him. He lived with his wife and three boys on a huge ranch up the hill, occupying the highest property in Aquilo. In the evenings, he would repair to his terrace with a good brandy and look out over the dim lights of Aquilo. He liked to sit there until it was dark, listening to the hum of all those Cantantes, which to him made the most pleasing music in all the world.

Seraphim amused himself by collecting horses; and by the time of our story, he had amassed an impressive stable that the villagers estimated at three thousand, though in reality the number was closer to seventy-five. Though he kept a few Tolfetanos and Swedish Ardennes, most of Seraphim’s horses were Lipizzans—those mighty warhorses beloved down the ages. But his favorite horse, the one on which he lavished the most attention, was a rare white Thoroughbred stallion named Markab. Markab was a true white horse (unlike the Lipizzans, which, as anyone who has done an afternoon’s research on this could tell you, are born dark and get progressively lighter as they age). Markab rose to almost eighteen hands high, and his eyes were the color of the twilight sky. On weekends, Seraphim would ride him down to the village, trotting a few laps around the square before taking Markab to El Rey’s for ice cream. The horse seemed to favor pistachio—always served on a sugar cone—a preference that the sycophant owner of El Rey’s enshrined in the menu by renaming a double scoop of pistachio El Markab. After their snack, man and horse would stand in the middle of the square to be admired. No one really remembers when the tradition started, but sometime in the years before the Great Crisis, one little boy had the courage to walk up to the horse and pat him. Others soon followed. Seraphim not only allowed this, but as time passed, he seemed to welcome it. Now and then he would direct a kind word to one of the children. A stranger seeing this—perhaps you—would regard Seraphim with a softened heart. You might begin to doubt what the Aquilinos said about him. Seraphim was becoming an old man, after all, and the kindness he showed the children was proof that in his powerful body there dwelled a gentle spirit. No. It is true that Seraphim was not all bad—who is?—but bear in mind that it is easy enough to be kind to children and cripples, especially when the evil of one’s ways makes one eager to mitigate one’s sins in the eyes of God and man. Believe me: the horse alone was blameless.

Though Seraphim doted on his Thoroughbred, he himself most closely resembled a Lipizzan. He had an unusually long head (even for an Aquilino), which sat atop a neck that arched back, giving him a bearing that accentuated his standoffish nature. His small ears were set high on his head and his flat Aquilino face (rather more convex in profile than normal) was dominated by his enormous brown eyes. When he was angry, which was often, his nostrils flared, revealing a tangle of white hair. He was powerfully built, from his wide chest to his muscular legs, which, in the summer, he was fond of showing off. This strong body, however, seemed to teeter on a pair of unusually small feet, an anatomical anomaly in Aquilo and one that invariably produced quiet snickers whenever he passed. In sum, Seraphim was not a good-looking man, and this shortcoming exacerbated his unpopularity, for as everyone knows, all sorts of sins are forgiven the beautiful.

Belafonte was such a creature. He was a bit above the average height of an Aquilino, and his light, thin limbs gave him the appearance of being even taller. One never saw him plodding along in Aquilo—no, Belafonte seemed to soar. To his many admirers, it seemed he was one and the same element with the wind that gamboled down those narrow streets of cobblestone. Though he was by then in his early thirties, Belafonte retained a delicate, boyish face and happy, curious eyes. It was a source of constant frustration to the mothers of the town that Belafonte had steadfastly refused marriage, preferring to spend solitary hours in his little thatched hut on the windiest bluff of Aquilo. He seemed to care for nothing else but making parachutes. And long after most of the Aquilinos had risen from their Cantantes and made their way to the village center for dinner and drinks, Belafonte remained at his machine. Often, when the villagers returned home from their late-night partying, they noticed that Belafonte’s light was still on and his graceful silhouette bent over his current production. They were just parachutes, but Belafonte showered them with the disproportionate love of the obsessed. Like most artists, he gave his creations much more attention than they were worth. These were, after all, only parachutes destined for distant wars, not royal boudoirs. And yet, you wouldn’t know it from examining the envelopes that Belafonte produced. It is really a shame that not one of those magnificent chutes survived: every one (except his final creation) burned on the fields of Europe. What a treasure the world lost—one of many it would never know. Belafonte took special care with even the standard-issue envelopes. Where others were content to stitch together the usual camouflage balloon as quickly as they could, Belafonte embellished even his ordinary works in subtle ways. Sometimes he would line the inside in iridescent silver, to give the falling airman the little bit of pleasure and private surprise that makes life worth living. Sometimes he would stitch sayings along the inner hem: Live thy life as if it were spoil and pluck the joys that fly. Belafonte stitched these by hand, in gold thread, on the inside, and there’s no proof that the terrified airmen even saw them. If one of them chanced to look up, what did he imagine on reading He rode upon a cherub, and did fly: yea, he did fly upon the wings of wind? And still, with no hope of readers for his work, Belafonte wrote. There’s no explanation for this impulse other than his innate playfulness, the inner joy that blows through certain people and rearranges notions, sweeps away cobwebs, transforms rigid ideas into odd and pliable shapes.

In fact, Belafonte had for some time been experimenting with alternative shapes. Of course, orders had to be filled, and the requisitions were exact: so many inches, so much weight distribution. Belafonte never forgot that his creations were, above everything, utilitarian things. He never went in for the dissident talk during the height of the European war, that proposed that Aquilo was indirectly increasing suffering around the world by supplying the war machine. Some of the younger men and women had called for a strike, suggesting that Aquilo’s expertise would be better directed at building touring balloons for the forthcoming Chicago World’s Fair. Belafonte would have none of that. The Aquilino envelopes were not just beautiful; they were lifesaving creations capable of buoying a man to safety. These were the big themes: fear and redemption. How could that compare to the antics of silly tourists in a hot air balloon? Belafonte would become even more animated than usual when talking of the soldiers his work was saving. What a feeling it must have been, he told me once in his shop, for those men—who moments before had been jolted out of their fiery machines—to find themselves floating silently, slowly, to earth. But the strikers got their way, at least for a while. And for about two months, parachute production almost came to a halt in Aquilo. Belafonte did his best to increase his pace, working sometimes through the night to fill the orders that were piling up. Understandably, he did not produce his best work during this time. But Aquilo met its targets and the contracts were saved—at least that time. When everyone returned to work, Belafonte returned to his art. Alternative shapes. Yes, for a while, as I said, Belafonte had been experimenting with alternative shapes. Though the others said that only bell shapes would fly, Belafonte proved that, with careful calculation, the wind could be distributed over an amazingly diverse number of surfaces. His first one was a balloon shaped like a giant apple, done up in shiny candy-red silk that Mauricio had brought in from the capital specially for him. No one in Aquilo will forget the day that Belafonte tested it, drifting down from a spot just above Seraphim’s ranch on a beautiful terciopielago that was blowing that day. By the time Belafonte floated over the square, most of the village had come out to watch. The children cheered. Beneath the giant apple, Belafonte seemed no bigger than its seed, a wisp of a man, hands outstretched as he faced the sea. Next came an almost exact replica of his cottage, complete with thatched roof: a cylindrical envelope that Belafonte had decorated with red and yellow flowers. This one he tested at dawn, when an horniento blew strong enough to propel even a real cottage over the foothills. Those villagers who were awake reported the flight as a sort of hallucination, as if Belafonte’s cottage had somehow come loose from its moorings to haunt their dreams.

The parachute maker managed these creations on his days off, for he continued to produce regulation canopies for the war effort, his Cantante singing regularly into the early morning hours. Now and then, he included one of his alternative forms in his shipment, expertly folding and packing it with the others. He liked to imagine the surprise of those soldiers who, having ejected from a burning plane or leaped out the chute door, machine gun in hand, found themselves suddenly floating to earth beneath a gold silken sun or a giant banana that rustled in the wind. Belafonte had hit a certain rhythm in his work and was happy.

But this story whirls and twirls in concentric circles, doesn’t it? And one day came the Great Crisis, though it’s important to note that “Great Crisis” is the name the villagers gave it afterward. At the beginning, no one could really know that anything like a Great Crisis was under way. Maybe a mini crisis, or a downturn, something that would blow over soon—that’s what everyone said when the first orders of the month came in ten chutes short of the previous month. Some of the parachute makers didn’t even notice, or if they did, they said it was due to the normal cycles of commerce and was nothing to worry about. The Aquilinos, understand, were more immune than most people to the battering winds of fate. They had just learned to take whatever came, adjust their paths through the valleys, turn their backs on the worst of it, and carry on. So they did.

The following month, the orders came in fifty short of the peak. But still there were some in the village who argued that pessimistic predictions were so much bluster. This went on for a few months, the orders falling or sometimes briefly rallying only to plunge even more. Then, as if matters weren’t already bad enough, the war ended.

Reports began seeping into Aquilo of a worldwide downturn in the business cycle. The chute orders trickled away to nothing. The silk bolts piled up in Mauricio’s storerooms. The nights of dinner and drinks grew fewer and fewer until the pub owners appealed to the villagers to return to their old ways. But though the villagers would have liked to, they could not. The little money that was left was needed for essentials. Restaurants and bars began to close. Where once the villagers had dined on caviar and imported cheeses, now they turned to the fruits of their own land, surviving on the old staples: black beans and bramble berries. A year into the crisis, when conditions were at their worst, a consortium of women hit on the idea of sewing backpacks and purses out of the stockpiled fabric. Soon Aquilo, the proud village that had turned out so many soaring monuments to freedom and possibility, was stitching together lightweight bags decorated with kittens and smiley faces. It was humiliating work, but it kept the village aloft for a while. Even Belafonte contributed to the efforts, turning out bright little purses on his Cantante. But he never abandoned his balloons. During those long dark months, he hung on to the lightness of his character by working on what was to be his last creation. He worked in secret, from a private pattern. But word got out about the absurd lengths of silk that he was buying from Mauricio. Some said Belafonte was building the world’s greatest balloon. Others thought he was being kind to Mauricio, simply relieving his old friend of excess inventory.

For half a year, Belafonte and the villagers were able to just break even with the income from their purses. But distribution was slow, and the market for their product as depressed as they were. Before long the people of Aquilo were forced to accept their new poverty. The nation may have been talking of a general recovery, but it was clear that, in Aquilo at least, the jobs were not retur...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- You Are the Heirs of All My Terrors

- Cojimar

- The Boy Who Was Rescued by Fish

- The Boy’s Triumphant Return

- In Defense of Flying

- Glossary of Caribbean Winds

- The Parachute Maker

- From: The Poets To: Herberto Quain

- From: Herberto Quain To: The Poets

- Redstone

- The Express

- Zodiac of Loss

- Journey Back to the Seed (¿Qué Quieres, Vieja?)

- The Boy Who Fell from Heaven

- The Poet in His Labyrinth

- Adios Happy Homeland: Selected Translations According to Google

- Un Cuento Extraño

- A Brief History of the Cuban Poets

- The Melancholy Hour

- End-less Stories

- Three Betrayals

- Voló Como Matías Pérez

- Traveling Fools

- The Shunting Trains Trace Iron Labyrinths

- Contributors’ Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Footnotes