eBook - ePub

Making Home from War

Stories of Japanese American Exile and Resettlement

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The sequel to the award-winning

From Our Side of the Fence—personal stories of life after the WWII internment camps from twelve Japanese Americans.

Many books have chronicled the experience of Japanese Americans in the early days of World War II, when over 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, were taken from their homes along the West Coast and imprisoned in concentration camps. When they were finally allowed to leave, a new challenge faced them—how do you resume a life so interrupted?

Written by twelve Japanese American elders who gathered regularly at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California, Making Home from War is a collection of stories about their exodus from concentration camps into a world that in a few short years had drastically changed. In order to survive, they found the resilience they needed in the form of community and gathered reserves of strength from family and friends. Through a spectrum of conflicting and rich emotions, Making Home from War demonstrates the depth of human resolve and faith during a time of devastating upheaval.

"I remember my release from Manzanar as scary and intense, but until now so little has been said about this aspect of the internment experience. This is an important book, its stories ground-breaking and memorable."—Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, author of Farewell to Manzanar

"A deeply moving accounting of life after imprisonment, its lingering stigma, and the true meaning of freedom."—Dr. Satsuki Ina, producer of Children of the Camps

Many books have chronicled the experience of Japanese Americans in the early days of World War II, when over 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, were taken from their homes along the West Coast and imprisoned in concentration camps. When they were finally allowed to leave, a new challenge faced them—how do you resume a life so interrupted?

Written by twelve Japanese American elders who gathered regularly at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California, Making Home from War is a collection of stories about their exodus from concentration camps into a world that in a few short years had drastically changed. In order to survive, they found the resilience they needed in the form of community and gathered reserves of strength from family and friends. Through a spectrum of conflicting and rich emotions, Making Home from War demonstrates the depth of human resolve and faith during a time of devastating upheaval.

"I remember my release from Manzanar as scary and intense, but until now so little has been said about this aspect of the internment experience. This is an important book, its stories ground-breaking and memorable."—Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, author of Farewell to Manzanar

"A deeply moving accounting of life after imprisonment, its lingering stigma, and the true meaning of freedom."—Dr. Satsuki Ina, producer of Children of the Camps

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making Home from War by Brian Komei Dempster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

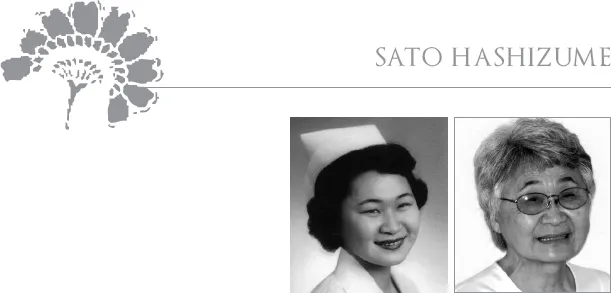

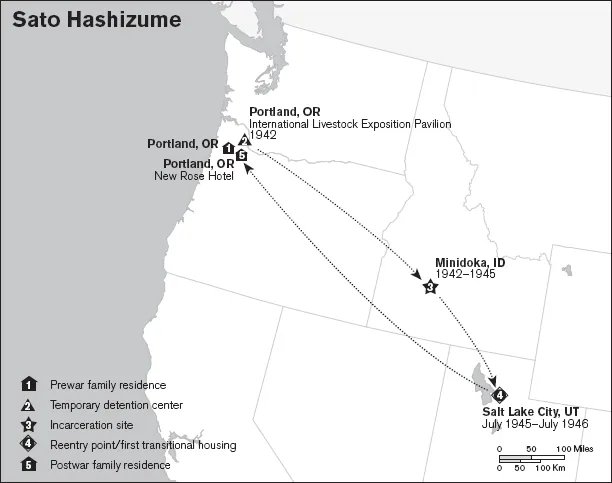

Sato Hashizume was born in Japan in 1931, raised in Portland, Oregon, and incarcerated during World War II in the Minidoka War Relocation Center, in southern Idaho. Without work or a home to return to after the war, her family relocated from camp to Salt Lake City, Utah, and after one year there, Sato’s father started a hotel business back in Portland. There, Sato received her nursing education at the Providence School of Nursing and her baccalaureate degree at the University of Oregon (now Oregon Health Sciences University). Later, during her graduate studies at the University of Minnesota (UM), she was inducted into Sigma Theta Tau, the nursing honors society.

Following her time at UM, she came to San Francisco and was employed by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), where she retired after twenty-six years of service as a teacher, administrator, and nurse practitioner. While at UCSF, she took a leave of absence to serve as a nurse educator aboard the hospital ship the USS HOPE at Sri Lanka. In her retirement years, she has been surprised and delighted with the unfolding of her life as she develops the craft of writing. An excerpt from her story “The Food” was first published in Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience, edited by Lawson Fusao Inada (Heyday Books, 2000).

LEAVING

The mess hall line was becoming shorter each day. Instead of the snaking queue along the side wall to the back door, the line had shrunk to about one third of what had been its usual length over the past four months. Last night about thirty people were ahead of me, including my neighbor Mary and Mr. and Mrs. Koike. Mrs. Sawada with her three small children stood behind me. I realized that I might never see these people again, so I wanted to linger and chat with them. We moved unhurriedly as we approached the “hash” tables.

“Where are all of you going?” I turned and asked Mrs. Sawada.

“I guess we’re going back to Portland,” she answered. “But I don’t know where all five of us will live. We’ll probably stay with my brother and his family in his two-room apartment until Fred can find a job. I can’t imagine how ten of us will fit in their tiny apartment,” she said with a half-laugh. “Maybe we’ll stay at the Japanese Methodist church. Toshie Muira, who works in administration, was saying that the churches were housing a few people from camp until they could get settled.”

I wish I were going to Portland with you, I thought to myself. I wouldn’t mind staying at the Methodist church. At least I would be back in Portland and know the people staying there.

“Aren’t you going to Portland too?” Mrs. Sawada asked Mary.

“I guess so, but I haven’t heard from Dad since last week,” Mary said. “So far, we don’t know where we’ll live either. We heard housing is scarce, and everyone is doubling up or living in basements. Someone said one couple was sleeping in a closet. Dad is helping a farmer in Troutdale, and hopefully he’ll have a place for us there. Who knows, we may have to stay in the farmer’s barn. We don’t know what we’re going to do, but Dad told us to get ready—we are leaving next week for sure.”

Well, at least Papa found a place for us to stay and had a job waiting for him, I thought.

“I’ll talk to Toshie this evening,” Mrs. Sawada said. “She seems to have more information than anyone else. She told Yuki that there might be openings not only in churches but in a housing project near the North Portland Assembly Center where we were forced to stay. The place is called Vanport or something like that. I’ll let you know what she says.”

As I reflected on the uncertainty of housing for the people returning to my hometown, I looked toward the Koikes, who had been quiet during our conversation.

“I don’t know what we’re going to do either,” Mrs. Koike said as she cast a worried look at her husband.

“Goddamn them!” Mr. Koike exploded. “I’m not leaving! They forced us in here and now they’re forcing us out. Where are we supposed to go? I don’t have anyplace to go to. They made me lose my grocery store, my home—everything. I don’t have money—no job—nothing. What am I supposed to do? I’m seventy-two years old. I’m not a kid anymore. What am I supposed to do? Goddamn those bastards. They’ll have to kick me out! I’m not leaving!”

While Mr. Koike’s bursts unsettled me, I think he expressed an anger that some other Issei must have felt but were uncomfortable giving voice to. After Mr. Funatake, the block manager, announced the closing of Minidoka at dinner one evening, Mr. Koike had bitterly complained to his neighbors. “How’s an old man like me supposed to find a job to support my family? How come no one from administration is helping us?” he would say. “Where are we supposed to live? Who’s going to pay for the rent and food?” Now, with the camp closure imminent, he could no longer contain himself. Questions swirled in my head: What will happen to Mr. Koike and his family if they refuse to leave camp? Will they be arrested? And if the mess hall closes, how will they get food?

I hesitated for a moment, allowing Mr. Koike to finish, then took my opportunity to say farewell to the neighbors in my block. “We’re leaving for Salt Lake City early in the morning before the mess hall opens,” I said. “So I want to say goodbye. Good luck, everyone. I hope we meet again someday.” As we separated to our different tables, I worried about how these people were going to manage. How unfair it is to force us out of camp without any help with jobs and housing, I thought. And with just twenty-five dollars each from the government for resettlement, what is going to happen when the money runs out?

I joined Kiyoko, who was sitting alone at a table that was once filled with our friends. As we ate our last watery, tasteless camp stew, my sister and I, lost in our thoughts, said very little for some time. I thought about “the Hermit.” No one had seen him for two or three weeks, and back when he would come to the mess hall from his desert tent, dirty rags hung from his gaunt frame. His eyes, glazed and vacant, stared at us all without recognition. “Have you heard anything about the Hermit?” I asked. “I wonder if he knows he has to leave?”

Kiyoko shook her head. “He looked so bad the last time I saw him, I don’t think he’ll make it if they send him back to Oregon. I hope someone helps him. He’s going to die if he stays in the desert much longer.”

“Talking about sick people, Mr. Tanaka’s been in and out of the hospital with a very bad heart and barely gets around,” I said, concerned, wondering how any of us with mental or health problems would manage the journey home and receive appropriate care. “What do you think Mr. Tanaka and his daughter will do?”

“Jean thought that she and her dad would take the train to Portland, where her uncle is staying,” Kiyoko said. “But I wonder if Mr. Tanaka can make the overnight trip. When he’s home he gets so out of breath taking a few steps that Jean brings his meals to the barracks. It’s a lot of responsibility for a seventeen-year-old.”

“When do you suppose they’ll leave?”

“I don’t know. I can’t keep track of people anymore,” Kiyoko said. “Everyone is so busy packing and moving that half the time they leave without telling anyone except their next-door neighbor. That’s how I found out about the Handas. They left so quickly, they didn’t drop by to tell us where they were going, and we’ve been friends for years. I don’t know where they went and when we’ll see them again, either.”

Kiyoko’s words rang true. It was a whirlwind of people leaving and scattering across the United States to places far from Portland. The changes were happening too fast, and I felt scared that I would never see this community again. I wondered, Will we ever see our friends again? How will we find them? And will they be able to find us?

My appetite gone, I pushed my tray away.

OUR BARRACK ROOM

In the early light of dawn, I took my final look around the barrack room, our home for the last three and a half years. Papa’s well-used, handcrafted bench would be left behind, along with the orange-crate shelves and the print fabric closet cover. Now faded and hanging askew, it revealed the empty shelves and wooden clothes-hanger pole. Kiyoko stripped down the four army cots to the mattresses. The other two beds, dusty and unused for the two years after my sister Shige and brother George had each left camp for Cincinnati, were left folded against the side wall. I smiled at the dull, discolored potbelly stove that made perfectly browned toast as we warmed ourselves. The crisp, fragrant bread was such a treat compared to the pale and soggy mess hall fare.

“Com’on, Sato, hurry up. The army truck is here,” Kiyoko called from outside, interrupting my thoughts.

“I’m coming,” I yelled back. I headed toward the entry and, bending slightly, patted the smooth surface of Papa’s bench. I was going to miss this room, a comfortable place where Tei and Mary had patiently taught me how to knit mittens. I remembered how the second mitten grew two sizes larger than the first but they profusely complimented my effort anyway. I now put on the hand coverings I had labored over and then worn just once, having hidden them in the bottom of the closet. I was more successful with the shells from Tule Lake that Mrs. Ogura shared so I could create my own shell corsage. “I can’t believe you made it,” Shige said in a letter when I sent the corsage to her for her birthday. I was pleased.

I was going to miss all my sister’s friends who stopped by with the latest gossip or to chat about old times in Portland. I felt a pang of loneliness when I thought of my friends, Jean and Setsuko, who lived in my block and recently moved away. We would while away many hours just hanging out and talking about the boys in our class. But mostly I was going to miss my buddies, Frances and Lucy, childhood friends since we were five years old. Frances had already left camp for Portland and Lucy went off to far-away St. Paul, Minnesota. And now I was headed without my friends to Salt Lake City. A little shiver went up my spine.

I stepped outside, closed the door, and hurried to the waiting transport truck.

MAKING ENDS MEET

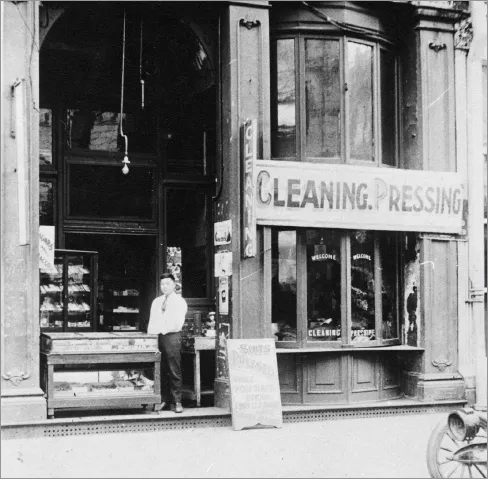

“Tomorrow, Papa is going to start working at a dry cleaning place,” Kiyoko said with a smile. “He’s lucky to get a job where he knows the ropes. And he’s a good tailor, too.”

Papa stands in front of his dry cleaning business. Portland, Oregon, 1921.

“Yeah, in camp he remade all those rejected army riding pants into straight-legged trousers,” I said. “And they looked pretty good with those sharp creases. The younger guys didn’t want anything to do with them, but the older men lined up with their jodhpurs for Papa’s makeover. Where did he learn to sew like that?”

“Before he went into the apartment house business full-time—about the time you were born—he had three small businesses: a dry cleaner, a cigar stand next door, and a ten-room apartment house above both of them,” Kiyoko answered. “He didn’t know anything about tailoring but learned from a client who showed Papa how he wanted his pants altered. Papa was amazed that the man paid for the alteration and then returned to have more trousers fixed.”

“I’m excited about him starting his new job,” I said. “I know he will do well.”

The following day Papa surprised us when he returned home before noon. We—Father, Kiyoko, Tom, and I—had moved into this house after our release from camp in July of 1945. Here, we rented two rooms from the landlord, a man of German and Jewish descent, and his wife. “Why are you home so soon?” I asked.

“Someone else took the job,” he said with a mirthless chuckle. “The Japanese owner was surprised to see me and said the job had been given to another man from a camp in Utah the day before. He apologized over and over as he explained that he wasn’t sure when I would return, and the new employee was already available.”

A knot formed in my stomach. I felt hurt and disappointed for Papa.

He didn’t waste any time focusing on his bad fortune, though. “Shoganai, it can’t be helped,” he said with a shrug and then combed the newspaper want ads. Since he had had his own businesses for much of his life, looking for employment was new to him. With limited English, and now in his late fifties, the task of finding a well-paying job would be daunting, but he was optimistic. The best position he found in the want ads was as a cook at the University Club. He had never cooked anything except rice before, but he thought he could learn on the job, as he had done in the past with railroad work, dry cleaning, tailoring, and managing an apartment business. After all, what could be so difficult to learn, he must have thought.

When Papa came home around noon on the day he had applied for the cook position, my heart sank. I thought he had lost another job, but he said that he was only on his break and would return to work at 3:00 p.m. for four more hours, this time as not a cook but a dishwasher. He laughed as he told us about his morning. “Ii ohanashi no tane. It’s a seed for a good story.” He would say this to us before launching into a funny story about himself.

“I arrived promptly at seven in the morning to prepare breakfast at the restaurant,” he began. “The first order was two eggs, ‘sunny-side up.’ I didn’t know exactly what to do, so I picked up the first egg and tried to crack it. My big, clumsy thumbs crushed the shell and broke the yolk all over my hands.” He chuckled. “I tried again and again, five times before the manager took me aside and asked if I had ever cooked in a restaurant before. I had to answer ‘no.’ The manager was very kind. He said, ‘I know you need work,’ then transferred me to dishwasher.” I laughed with Papa but felt he deserved a better job.

From late summer until winter, we settled into our German-J...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Migration Maps

- Florence Ohmura Dobashi

- Kiku Hori Funabiki

- Sato Hashizume

- Fumi Manabe Hayashi

- Naoko Yoshimura Ito

- Florence Miho Nakamura with Kristen Langewisch Marchetti

- Ruth Y. Okimoto, Ph.d

- Yoshito Wayne Osaki with Sally Noda Osaki

- Toru Saito

- Daisy Uyeda Satoda

- Harumi Serata

- Michi Tashiro

- Appendix A: Lesson Plans

- Appendix B: Overview of Migration:

- Bibliography

- About the Editor