- 385 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

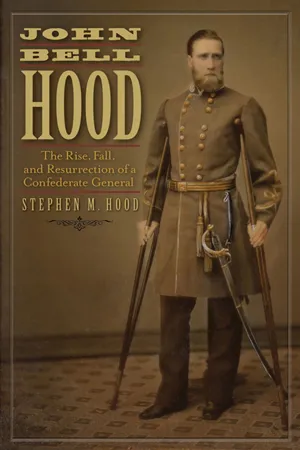

An award-winning biography of one of the Confederacy's most successful—and most criticized—generals.

Winner of the 2014 Albert Castel Book Award and the 2014 Walt Whitman Award

John Bell Hood died at forty-eight after a brief illness in August 1879, leaving behind the first draft of his memoirs, Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies. Published posthumously the following year, the memoirs immediately became as controversial as their author. A careful and balanced examination of these controversies, however, coupled with the recent discovery of Hood's personal papers—which were long considered lost—finally sets the record straight in this book.

Hood's published version of many of the major events and controversies of his Confederate military career were met with scorn and skepticism. Some described his memoirs as merely a polemic against his arch-rival Joseph E. Johnston. These opinions persisted through the decades and reached their nadir in 1992, when an influential author described Hood's memoirs as a bitter, misleading, and highly biased treatise replete with distortions, misrepresentations, and outright falsifications. Without any personal papers to contradict them, many writers portrayed Hood as an inept, dishonest opium addict and a conniving, vindictive cripple of a man. One went so far as to brand him a fool with a license to kill his own men.

What most readers don't know is that nearly all of these authors misused sources, ignored contrary evidence, and/or suppressed facts sympathetic to Hood. Stephen M. Hood, a distant relative of the general, embarked on a meticulous forensic study of the common perceptions and controversies of his famous kinsman. His careful examination of the original sources utilized to create the broadly accepted facts about John Bell Hood uncovered startlingly poor scholarship by some of the most well-known and influential historians of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These discoveries, coupled with his access to a large cache of recently discovered Hood papers, many penned by generals and other officers who served with Hood, confirm Hood's account that originally appeared in his memoir and resolve, for the first time, some of the most controversial aspects of Hood's long career.

Winner of the 2014 Albert Castel Book Award and the 2014 Walt Whitman Award

John Bell Hood died at forty-eight after a brief illness in August 1879, leaving behind the first draft of his memoirs, Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies. Published posthumously the following year, the memoirs immediately became as controversial as their author. A careful and balanced examination of these controversies, however, coupled with the recent discovery of Hood's personal papers—which were long considered lost—finally sets the record straight in this book.

Hood's published version of many of the major events and controversies of his Confederate military career were met with scorn and skepticism. Some described his memoirs as merely a polemic against his arch-rival Joseph E. Johnston. These opinions persisted through the decades and reached their nadir in 1992, when an influential author described Hood's memoirs as a bitter, misleading, and highly biased treatise replete with distortions, misrepresentations, and outright falsifications. Without any personal papers to contradict them, many writers portrayed Hood as an inept, dishonest opium addict and a conniving, vindictive cripple of a man. One went so far as to brand him a fool with a license to kill his own men.

What most readers don't know is that nearly all of these authors misused sources, ignored contrary evidence, and/or suppressed facts sympathetic to Hood. Stephen M. Hood, a distant relative of the general, embarked on a meticulous forensic study of the common perceptions and controversies of his famous kinsman. His careful examination of the original sources utilized to create the broadly accepted facts about John Bell Hood uncovered startlingly poor scholarship by some of the most well-known and influential historians of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These discoveries, coupled with his access to a large cache of recently discovered Hood papers, many penned by generals and other officers who served with Hood, confirm Hood's account that originally appeared in his memoir and resolve, for the first time, some of the most controversial aspects of Hood's long career.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access John Bell Hood by Stephen M. Hood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

“History to be above evasion must stand on documents, not on opinion.”

— Lord Acton

John Bell Hood: The Son and the Soldier

Regardless of the subject, it is difficult to find unanimity of opinion among Civil War historians. But when considering the enigmatic career of Confederate General John Bell Hood, both pro- and anti-Hood historians would probably agree that the life and career of the native Kentuckian was extraordinary.

Hood’s meteoric rise and precipitous fall paralleled that of the Confederacy. His remarkable successes at the head of the Texas brigade in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in 1862 made him a star of Richmond society, a genuine public hero, and a favorite of the government and high command. Arguably, Hood and the Confederacy reached their apex in 1863 just before Lee’s invading army was defeated at Gettysburg, where Hood suffered his first serious wound while leading a division of infantry in an assault against General Dan Sickles’s III Corps on the afternoon of July 2.

Although he is associated with Texas troops, Hood was not a native Texan. The dashing charismatic leader was born in Owingsville, Bath County, Kentucky, on June 29, 1831, and reared in the rural Montgomery County community of Reid Village near Mount Sterling. The son of a scholarly rural doctor, John was heavily influenced by his grandfathers—one a crusty veteran of the French and Indian War and the other a Revolutionary War veteran. Hood’s grandfathers were his primary male influences during the early 1830s while his father, John W. Hood, was absent on frequent trips to Pennsylvania studying medicine at the Philadelphia Medical Institute under a prominent physician believed to have been John Bell Hood’s namesake, Dr. John Bell.1

Philadelphia’s Dr. Bell, a native of Ireland, had studied medicine in Europe and in 1821 had attended the commencement ceremonies at Transylvania College in Lexington, Kentucky, near the Winchester, Kentucky, home of the aspiring young doctor John Hood. Since John Hood’s two older brothers were also physicians, it is likely that the future doctor John W. Hood met Dr. John Bell in Kentucky in 1821.2

The adventurous life of a soldier appealed to the younger Hood, who gained an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1849. It was there he received his nickname “Sam.” Although no written explanation for the source of the nickname has been found, many of his modern descendants believe his classmates tagged him with the moniker after the famous British war hero, Admiral Samuel Hood (1724-1816), viscount of Whitley, whose naval exploits in the late 18th century were studied by West Point students in the mid-19th century. Academically Hood struggled at the academy. He graduated in 1853 near the bottom of his class (44 out of 52), though he was nearly removed from West Point in his last year when he bumped up against the demerit limit.3

Hood’s first assignment in the U.S. Army was in the rugged and untamed environs of northern California, where the young second lieutenant of cavalry served at Fort Jones. Described by Hood’s comrade Lt. George Crook (later a Federal general in the Civil War) as “a few log huts built on the two pieces of a passage plan,” the fort was established in October 1852 to protect miners and pioneer farmers from Indians.4

Hood’s duties consisted primarily of commanding cavalry escorts for surveying parties into the rugged mountainous regions near the California-Oregon border. His final escort mission was in the summer of 1855, when he accompanied a party led by Lt. R. S. Williamson of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers to explore and survey a railroad route from the Sacramento River Valley to the Columbia River. On August 4, Lt. Philip Sheridan (who would later become a prominent Federal cavalry commander) overtook the Williamson surveying expedition with orders to relieve Hood, who was instructed to return to northern California’s Fort Reading and then proceed east for a new assignment in Texas. “Lt. Hood started this morning with a small escort, on his return to Fort Reading,” Williamson wrote in his journal on August 5, “much to the regret of the whole party.”5

“The duty of repressing hostilities among the Indian tribes, and of protecting frontier settlements from their depredations,” wrote Secretary of War Jefferson Davis in September of 1853, “is the most difficult one which the Army has now to perform; and nowhere has it been found more difficult than on the Western frontier of Texas.” After nearly two more years of little progress, Davis authorized in 1855 the formation and equipping of two new regiments of cavalry, whose mission was to suppress hostile Indian activity on the Texas frontier. One of these was the U.S. Second Cavalry Regiment.

The vast majority of U.S. Army officers (either veterans of the war with Mexico or recent graduates of West Point) were bored and despondent over the dull routine of an inactive or fading military career. For them, the news of the formation of new cavalry regiments—an active assignment, coupled with the possibility of long-overdue promotions—was greeted with genuine enthusiasm. Among the fortunate few assigned to the new cavalry regiments were future Civil War notables Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, Major William J. Hardee, Major George H. Thomas, Captain Earl Van Dorn, and Second Lieutenant John Bell Hood.

A year passed, during which Hood traveled east from his northern California duty station, spent time in Kentucky, and then made his way at last to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, where the Second Cavalry Regiment was organized and outfitted. After reporting for duty to Lieutenant Colonel Lee in Texas in January of 1857, Hood soon transferred to serve under Major Thomas at Fort Mason, a stronghold built in 1851 on Post Oak Hill near Comanche and Centennial creeks in what would later be Mason County.

On July 5, Hood led a 24-man cavalry expedition south from the relative safety of the fort, embarking on what would become an extremely long and hazardous search for a renegade Indian war party reported to be in the remote and desolate area of the appropriately named Devil’s River. On July 20, the patrol encountered 40 to 50 heavily armed mounted Comanche warriors and a hand-to-hand battle ensued. Hood, who was still mounted, suffered his first combat wound when an arrow pierced his left hand, pinning it to his saddle. Hood broke the arrow, freed his injured limb, discharged his shotgun, and then drew his Colt Navy revolvers, emptying the 12 rounds pointblank at his attackers. The Comanches killed two troopers and wounded several more during the initial round of fighting.

Unable to reload under such pressing conditions, Hood ordered a retreat. The troopers fell back and regrouped in the rear, where they prepared for another assault from the warriors. Much to the relief of Hood and his men, the Comanches ceased their attack and withdrew overnight, taking their dead with them. Hood praised his soldiers, writing in his official report, “It is due my non-commissioned officers and men, one and all … during the action they did all men could do, accomplishing more than could be expected from their number and the odds against which they had to contend.”6

Hood resigned his U.S. Army commission on April 16, 1861, shortly after the bombardment of Fort Sumter and the outbreak of the Civil War, and enlisted in the Confederate Army. For a second time since their days at West Point he was reunited with Robert E. Lee, his former superintendent at the Academy. The young soldier reported to Lee in the Confederate capital at Richmond in the summer of 1861 and was assigned to the Virginia peninsula, where Confederate infantry and cavalry units were being organized and trained. Rapid promotions followed. Hood’s first command was as colonel of the 4th Texas Infantry Regiment. He was promoted to brigadier general on March 6, 1862, and appointed commander of the Texas brigade, a mixed outfit of Texans, Georgians, and South Carolinians.7

Hood’s decision to wear the blue or the gray had not been an easy one. On September 27, 1860, he declined a coveted assignment as an instructor of cavalry at West Point because he feared that civil war would soon break out, and he “preferred to be in a situation to act with entire freedom.” Instead of accepting the prestigious West Point offer, he took an extended furlough from the Second Cavalry and spent the fall and winter of 1860 in his native Kentucky, waiting to see how the sectional crisis would evolve. He was still on furlough when he returned to Camp Wood, Texas, in January 1861. “I see that dissolution is now regarded as a fixed fact. And that Kentucky will have an important part to perform in this great movement,” Hood wrote on January 15 to Beriah Magoffin, the governor of Kentucky. “I thereby have the honor to offer my sword & services to my native state. And shall hold myself in readiness to obey any call the Governor of said state may choose to make upon me.”

On April 15, three days after the attack on Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln called upon Governor Magoffin to provide four regiments to assist in suppressing the rebellion. Magoffin flatly refused and Lincoln dared not insist, for fear that he would drive Kentucky into the Confederacy. By April 16 Hood had lost his patience: “I have the honor to tender the resignation of my Commission as 1st Lieutenant 2nd Cavalry U.S. Army—To take effect on this date.” His resignation was approved by the Secretary of War on the 25th and announced on the 27th. By then, Hood was already a first lieutenant of cavalry in the Confederate Army, and on his way back to Kentucky to recruit.8

By the end of April 1862, the focus of Confederate and Union military operations had moved from the environs of northern Virginia to the peninsula between the York and James rivers. Federal General George B. McClellan had transferred the bulk of his Army of the Potomac by water to Fort Monroe and was endeavoring to move up the peninsula to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond from the east. The strong fortifications at Yorktown and heavy rains, however, convinced McClellan to commence siege operations. Just hours before his artillery barrage was to begin, General Joseph Johnston withdrew his Confederate army from the Yorktown entrenchments and retreated west toward Richmond, followed by a brisk rearguard action at Williamsburg on May 5. Correctly assuming that McClellan would use the York River as a means of flanking his line of retreat, on the same day Williamsburg was raging Johnston ordered General Gustavus W. Smith’s division, including the Texas brigade, to march hastily toward Richmond via Barhamsville, a small town a few miles inland from the headwaters of the York River.

By the morning of May 7, Johnston had most of his Confederate army positioned around Barhamsville. Smith’s division, situated northeast of town, protected the army’s main line of retreat toward Richmond. Johnston’s fears of a Federal flanking maneuver by water were soon realized when Generals William B. Franklin and John Sedgwick landed with their divisions at Eltham’s Landing near the head of the York River. The enemy column was only two miles from the road that was crowded with Johnston’s retreating supply trains. To ensure that no Federals were moving to threaten the Confederate line of retreat, Johnston sent a portion of Smith’s division under General William H. C. Whiting toward the enemy position. Whiting’s orders were simple: drive the enemy back far enough so they could not threaten the Confederate withdrawal.

When orders arrived from Whiting, Hood marched his brigade forward at 7:00 a.m. In a bid to avoid accidental discharges that might reveal his position and also incur friendly fire losses, Hood’s men moved through the heavy woods with unloaded muskets. After an uneventful march of about one mile, with Hood riding at the head of the column, the troops entered an open field that rose to a small hill upon which stood a small cabin. Hood ordered Company A of the 4th Texas to form in line at the base of the hill, followed by the rest of the regiment, and spurred his own horse up the slope with a staff member and courier to reconnoiter. The small party was approaching the crest when a squad of Federals appeared from the other side of the cabin. The men belonged to the 16th New York, and had climbed the height’s steep counter-face while Hood and his aides ascended the gentler slope on the other side. Stunned by the sudden appearance of their opponents and just paces apart, everyone involved froze. After a short pause Hood and his companions instinctively turned their horses to provide cover, quickly dismounted, and sprinted back to the nearby Confederate line as the New Yorkers opened fire.

The unexpected appearance of the enemy, combined with their unloaded weapons, threw the Texans into confusion. Many scurried for any cover they could find. Hood was rallying his men when a Federal corporal named George Love raised his weapon and took aim at the Rebel general. Before he could pull the trigger, however, a Texan kneeling behind a stump fired first. The round whizzed past Hood and killed Love instantly. Hood’s savior was John Deal, a private in the 4th Texas whose unsuccessful hunting expedition the night before had left him with the only loaded gun in the regiment.

Hood’s brigade, along with the balance of Whiting’s division, forced the Federals back to the York River landing and the protection of their gunboats. Whiting shelled the enemy position without much effect. The battle of Eltham’s Landing was a well-fought heavy skirmish that secured the Confederate retreat route to Richmond at the cost of fewer than 50 Southern killed and wounded (Union losses were about 200). It was also the first Southern victory on the Peninsula. G. W. Smith praised Hood’s brigade for having earned “the largest share of the honors of the day at Eltham,” while Whiting wrote of Hood’s “conspicuous gallantry.” The Texas brigade was once again designated as the rearguard of the army as it continued withdrawing toward Richmond. Eltham’s Landing established the brigade’s early reputation as a hard-fighting unit, and Hood demonstrated capable and aggressive leadership in the fight.9

It is fair to say that the battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) on May 31 and June 1, 1862, changed the course of the war in the Eastern Theater and with it, Hood’s career. When Joseph E. Johnston fell severely wounded near the end of the first day of his botched offensive, President Jefferson Davis appointed Gen. Robert E. Lee to command the Virginia army, which would become famous under Lee as the Army of Northern Virginia.

In the Seven Days’ Battles (fought the last week of June and the first day of July), Lee ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 John Bell Hood: The Son and the Soldier

- Chapter 2 Robert E. Lee’s Opinion of John Bell Hood

- Chapter 3 Jeff Davis, Joe Johnston, and John Bell Hood

- Chapter 4 The Cassville Controversy

- Chapter 5 The Battles for Atlanta: Hood Fights

- Chapter 6 Desperate Times, Desperate Measures: The Tennessee Campaign

- Chapter 7 John Bell Hood: Feeding and Supplying His Army

- Chapter 8 Frank Cheatham and the Spring Hill Affair

- Chapter 9 John Bell Hood and the Battle of Franklin

- Chapter 10 The Death of Cleburne: Resentment or Remorse?

- Chapter 11 John Bell Hood and the Battle of Nashville

- Chapter 12 The Army of Tennessee: Destroyed in Tennessee?

- Chapter 13 Did John Bell Hood Accuse His Soldiers of Cowardice?

- Chapter 14 A Callous Attitude: Did John Bell Hood “Bleed His Boys”?

- Chapter 15 John Bell Hood and Frontal Assaults

- Chapter 16 Hood to His Men: “Boys, It is All My Fault”

- Chapter 17 John Bell Hood and Words of Reproach

- Chapter 18 Words of Praise for John Bell Hood

- Chapter 19 John Bell Hood: Laudanum, Legends, and Lore

- Afterword

- Appendix 1 Excerpt from Advance and Retreat

- Appendix 2 “An Eloquent Tribute to the Memory of the Late Gen. J. B. Hood”

- Appendix 3 Jefferson Davis on Joe Johnston: Excerpt to the Confederate Congress

- Bibliography

- Index