![]()

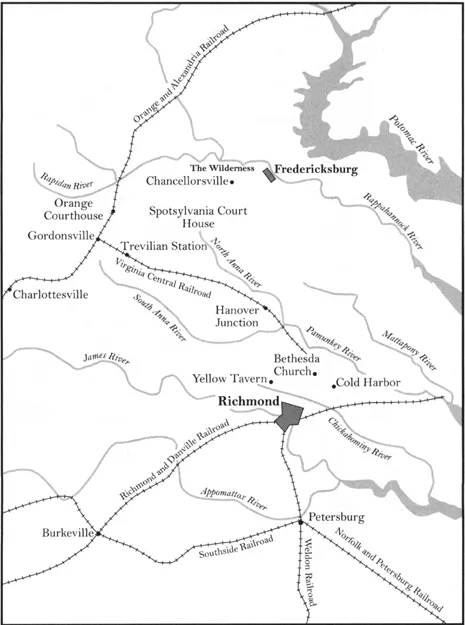

1: The Wilderness and Spotsylvania, May 1864

I am heartily sick of blood & the sound of artillery & small arms & the ghastly, pale face of death and all the horrible sights & sounds of war. I long more intensely & earnestly for the sweet rest & quiet of home than ever before.

—Capt. Benjamin Wesley Justice Commissary, Kirkland/Heth/III Corps, to his wife, 20 May 1864

In the days just before the spring campaign opened, a dramatic event occurred in the army that some soldiers might have interpreted as a sign. On the morning of 2 May, several units of the First Corps marched a few miles to new camps near Gordonsville. They had barely gotten settled when they were drenched and buffeted by “a heavy Storm from N.W. blowing down our tents, and the trees and creating a general stampede … the gale followed by a hard rain several narrow escapes from flying limbs by our boys,” according to a member of the famed Texas Brigade.1 Less than a week later the Texans and the rest of the army would find themselves in the midst of a quite different storm, with its own general stampedes and narrow escapes. At least one high-ranking observer thought that the thunderstorm might postpone fighting for a few more days. Brig. Gen. Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s brilliant chief of artillery, wrote his wife, “We have just had a tremendous storm & the weather is very chilly & damp (of course) but as it may give us a longer time to prepare for Grant I am very glad to see it.”2 By the next day, however, the weather had improved enough for drill and a sham battle in the Texas Brigade and for a preliminary movement by elements of Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins’s South Carolina brigade, also in the First Corps.3 “This closing towards the front indicates something but what it is impossible to say,” noted a colonel in Jenkins’s Brigade. “It serves this purpose with soldiers (however unsatisfactory it may be in women and citizens), namely, it puts them in a condition to be surprised at nothing.”4

With months of uncertain waiting behind them, and with certain battles immediately ahead of them, officers and men throughout the army wrote their families and friends in the first few days of May. Their letters, describing preparations for the coming fight and making their own predictions for the future, were often a blend of hope and fear, of confidence and apprehension. “Dear wife their is more talk a bout peace now then ever I herd of before,” Sgt. Isaac Lefevers of the 46th North Carolina commented, “but I am afraid it is only Sine for a big fite Shortley.” Lefevers, like many of his comrades, had alternating, if not contradictory, feelings about what lay ahead. “We all feel assured that if Grannt makes an attact hear that by the assistance of the almighty we will give him what he wont like,” he reported, but then cautioned, “all tho I have no doubt a meney one of us will fall in the Strougle.”5 Lefevers’s simple words were echoed by Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton’s more polished but no more heartfelt observation: “I hope confidently for success, but at the same time I cannot feel but anxious. In any event, how many thousand of the brave hearts, now eager for the strife, will have ceased to beat when that great fight is over!”6 One Virginian, a member of Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s Brigade in the Third Corps, had given much thought to the army’s past performance and its future prospects. “I find but few who agree with me,” Robert Mabry wrote his wife. “I can see no more reason now for a defeat of the Yankee Army bringing them to terms than heretofore.” After listing the Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns since Lee took command, and claiming that Gettysburg was the only defeat during that period, he asked rhetorically, “Where is the good resulting from all these victorys[?]” He thought Grant’s defeat “almost certain” but saw “little reason for believing it will close the war,” then ended his discussion with the optimistic but not entirely convincing words, “I humbly trust we may have an early peace.”7 Many of Lefevers’s, Hampton’s, and Mabry’s fellow soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia undoubtedly displayed similar conflicting emotions on the eve of the campaign.8

The Overland Campaign: The Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May—June 1864

The army’s large-scale preparations and troop movements were launched in earnest on 4 May. Lee discovered that the Army of the Potomac was massed north of the Rapidan River and crossing it in force close to where the two armies had met a year before at Chancellorsville. The Federals had some 118,000 effective troops, whereas the Confederates had about 62,000 officers and men, or a little more than half of that number, present for duty. Lee immediately ordered Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps and Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill’s Third Corps to check the Federal advance and Longstreet’s First Corps to follow.9 A sermon in the Third Corps was interrupted by orders “to strike tents, cut them up and distribute them among men, cook up rations and hold ourselves in readiness to march,” an Alabama lieutenant wrote his wife that afternoon.10 When Grant attacked Lee in the nearly impenetrable forest, thickets, and underbrush of the Wilderness early the next morning, he initiated a campaign—or series of campaigns—that would not end until the next April at Appomattox.11

Fighting on 5 May was heavy but resolved nothing. Lee, preferring not to fight a general engagement until his entire force arrived, kept the Second and Third Corps primarily on the defensive. The initial Federal assault, on the Confederate left, created considerable disorder in Ewell’s corps and achieved some early success. When the Second Corps received reinforcements and counterattacked, however, the offensive stalled. Ewell spent the rest of the day and early evening turning back further Union attempts to break his line or turn his flank. Federal advances that afternoon, on the right against the Third Corps, were somewhat more effective. Though Hill held his position, his troops were greatly disorganized and weakened by the constant pressure, and though Lee’s lines were intact at nightfall they would not remain so long. Poor communication between Ewell and Hill, combined with the usual confusion of battle and the natural obstacles of the Wilderness itself, allowed a gap between their corps. Grant would quickly exploit the opportunity presented by that costly error.

Early on the morning of 6 May, after repulsing an attack by Ewell, the Federals launched an offensive against Hill’s weak position. The Third Corps fell back in disarray but was soon supported by elements of the Second Corps and of Longstreet’s First Corps, just arriving on the field. By midday Longstreet found the Federal left flank exposed and committed a large portion of his force in an attempt to turn it. But the maneuver stalled when Longstreet was accidentally wounded by his own men. Fighting throughout the afternoon was characterized by Confederate frontal assaults that achieved little. Just before dark Ewell, on the other end of the line, discovered that Grant’s right flank was unprotected. Though initially successful, the Second Corps’s assault there was blunted by Confederate delays and Federal reinforcements, and darkness fell without either side gaining a tactical victory.’12 After two days of fierce combat, in which Grant lost nearly 18,000 casualties and Lee lost some 10,000 killed, wounded, and captured, the battle ended in a stalemate.

Combat in the Wilderness was defined by the forbidding region itself. The forest—primarily one of scrub pines and oaks—was overgrown with vines, briars, and other tangled vegetation, and it was divided by many small creeks and swampy areas. These features placed severe constraints on troop movements, on formations, on communication and coordination between units, and on visibility. Though officers in both armies attempted to create and exploit opportunities for flanking maneuvers, they were more often reduced to sending reinforcements into existing tactical situations. This was, above all, an infantry battle, in which elements of divisions, brigades, and regiments became hopelessly intermingled and in which individual soldiers often fought each other. When an officer in the 6th Louisiana wrote, “our Brigade got into the thickest of it,” he referred to the terrain as much as to the combat.13

Confederate descriptions and assessments of the fighting shared several common characteristics. Accounts in letters and diaries, and to a lesser extent in official reports, often illustrated their authors’ inability to write clear narratives describing their experiences. Such phrases as “a perfect wilderness,” “a boundless forest,” or “undergrowth almost impossible to penetrate,” for example, were used to convey the difficulties encountered by the Army of Northern Virginia.14 Some writers made explicit references not only to the Wilderness but also to the obstacles it created in the disposition of troops and in the use of arms other than infantry. Capt. James Hays, a staff officer in the Third Corps, wrote, “we have fought them in dense woods, only with musketry, & the Bayonet.”15 “I have never before seen woods so riddled with bullets,” a South Carolinian in the same corps marveled after the battle. “At one place the battle raged among chinquapin bushes. All the bark was knocked off and the bushes are literally torn to pieces.”16 In their official reports of the Wilderness, officers described the challenges they faced in moving, positioning, and leading troops under such conditions. “The dense character of the woods in which the line was formed render[ed] it impossible for either men or officers to see the character or numbers of the enemy we were to attack,” noted Brig. Gen. Goode Bryan, commanding a Georgia brigade.17 The colonel of the 1st South Carolina reported that a regiment that should have been in line next to his was nowhere to be seen when an advance began. “In the density of the forest [1] concluded it had temporarily gotten lost,” he wrote, “and I gave no more thought to it.”18

This confusion helped create situations in which troops blindly fired at noises or at shadows, and in which they killed and wounded their comrades instead of the enemy. When William Mahone’s Virginians of the Third Corps fired into a group of high-ranking officers on 6 May, it was only the most notable of several such occurrences in the Army of Northern Virginia. The volley from Mahone’s Brigade injured James Longstreet, mortally wounded Micah Jenkins, and killed two members of Joseph Kershaw’s staff. Most significantly, the mishap deprived the First Corps of its commander at a crucial juncture in the Confederate counterattack. Many observers in the army mentioned Longstreet’s wounding, eerily close to the scene where Stonewall Jackson had been accidentally shot by his own troops almost a year to the day earlier. Some believed that the mishap kept Lee from winning a decisive victory in the Wilderness. Longstreet himself told one staff officer that he was wounded “in the very achievement of victory but his plans were frustrated when he fell,” and another officer in the corps wrote a few days later, “Gen Longstreets wound I believe alone prevented us from routing Grants whole army on the 6th.”19 Similar accidents befell the 18th North Carolina, which “became somewhat confused, and commenced to fall back” when caught between Confederate and Federal fire, and the 12th Virginia, which was fired on by its own brigade, losing “some of [its] bravest and best men.” Sgt. John F. Sale of the latter regiment observed that “the loss of these was more deeply regretted than of those who were shot by the enemy.”20

Artillerymen and cavalrymen took relatively little part in the fighting but were keen observers of the battle. Some artillery batteries, placed on or near the few roads in the area or in the even fewer clearings, added firepower to Confederate defensive positions. The Second and Third Corps artillery, in limited action, “assisted materially in driving back the enemy” and participated “as far as the nature of the country permitted.”21 The First Corps artillery, however, remained in rear of the corps infantry and was not engaged. Its commander spent several hours “trying to find a place to get our arty to aid in the battle [but] could find none” and returned to corps headquarters.22 Elements of Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry corps helped guide units through the woods, scouted to establish enemy troop positions, clashed with Federal pickets and skirmishers, and fought dismounted in support of infantry as needed. “Some Yankee prisoners remarked in my hearing today that ‘that 4th Regt. fought like very Devils,’” a captain in the 4th Virginia Cavalry wrote proudly. “Our whole Division has been fighting just as Infantry most of the time in fact could only fight in that way in that Wilderness country.”23 It was, as a courier in the Third Corps observed, “almost entirely a musketry fight.”24

One notable response to tactical obstacles was the extensive use of skirmishers or sharpshooters. Both armies, by this stage of the war, had gradually increased their employment of skirmish lines and had created special units, most often battalions, of sharpshooters. Such troops, with their tactical flexibility, seemed particularly suited to operations in the Wilderness. A North Carolina lieutenant described the experiences of his sharpshooters during the first day’s fighting, which were typical. “We skurmished till late in the Eave at which time we advanced & run them back gaining some ground & held it,” he wrote. “They kept up some fireing all night but we were relieved by a co of the 32d Regt so we got to rest & sleep all night.”25 On the same day Capt. George P. Ring of the 6th Louisiana was writing his wife when a Federal assault interrupted his letter in midsentence. “I am now out with my co. skirmis...