- 289 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

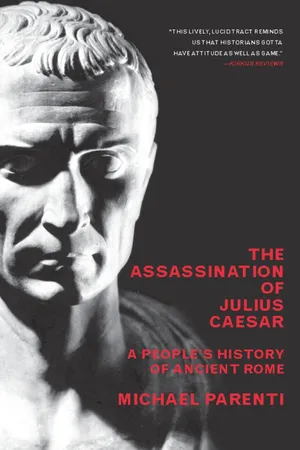

“A provocative history” of intrigue and class struggle in Ancient Rome—“an important alternative to the usual views of Caesar and the Roman Empire” (Publishers Weekly).

Most historians, both ancient and modern, have viewed the Late Republic of Rome through the eyes of its rich nobility—the 1 percent of the population who controlled 99 percent of the empire’s wealth. In The Assassination of Julius Caesar, Michael Parenti recounts this period, spanning the years 100 to 33 BC, from the perspective of the Roman people. In doing so, he presents a provocative, trenchantly researched narrative of popular resistance against a powerful elite.

As Parenti carefully weighs the evidence concerning the murder of Caesar, he adds essential context to the crime with fascinating details about Roman society as a whole. In these pages, we find reflections on the democratic struggle waged by Roman commoners, religious augury as an instrument of social control, the patriarchal oppression of women, and the political use of homophobic attacks. The Assassination of Julius Caesar offers a whole new perspective on an era thought to be well-known.

“A highly accessible and entertaining addition to history.” —Book Marks

Most historians, both ancient and modern, have viewed the Late Republic of Rome through the eyes of its rich nobility—the 1 percent of the population who controlled 99 percent of the empire’s wealth. In The Assassination of Julius Caesar, Michael Parenti recounts this period, spanning the years 100 to 33 BC, from the perspective of the Roman people. In doing so, he presents a provocative, trenchantly researched narrative of popular resistance against a powerful elite.

As Parenti carefully weighs the evidence concerning the murder of Caesar, he adds essential context to the crime with fascinating details about Roman society as a whole. In these pages, we find reflections on the democratic struggle waged by Roman commoners, religious augury as an instrument of social control, the patriarchal oppression of women, and the political use of homophobic attacks. The Assassination of Julius Caesar offers a whole new perspective on an era thought to be well-known.

“A highly accessible and entertaining addition to history.” —Book Marks

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Assassination of Julius Caesar by Michael Parenti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historiography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Gentlemen’s History: Empire, Class, and Patriarchy

Rome, thou hast lost the breed of noble bloods!

The writing of history has long been a privileged calling undertaken within the church, royal court, landed estate, affluent town house, government agency, university, and corporate-funded foundation. The social and ideological context in which historians labor greatly influences the kind of history produced. While this does not tell us everything there is to know about historiography, it is certainly worth some attention.

Historians are fond of saying, as did Benedetto Croce, that history reflects the age in which it is written. The history of seemingly remote events vibrate “to present needs and present situations.” Collingwood made a similar point: “St. Augustine looked at Roman history from the point of view of an early Christian; Tillemont, from that of a seventeenth-century Frenchman; Gibbon, from that of an eighteenth-century Englishman …”1

Something is left unsaid here, for there is no unanimity in how the people of any epoch view the past, let alone the events of their own day. The differences in perception range not only across the ages and between civilizations but within any one society at any one time. Gibbon was not just “an eighteenth-century Englishman,” but an eighteenth-century English gentleman; in his own words, a “youth of family and fortune,” enjoying “the luxury and freedom of a wealthy house.” As heir to “a considerable estate,” he attended Oxford where he wore the velvet cap and silk gown of a gentleman. While serving as an officer in the militia, he soured in the company of “rustic officers, who were alike deficient in the knowledge of scholars and the manners of gentlemen.”2

To say that Gibbon and his Oxford peers were “gentlemen” is not to imply that they were graciously practiced in the etiquette of fair play toward all persons regardless of social standing, or that they were endowed with compassion for the more vulnerable of their fellow humans, taking pains to save them from hurtful indignities, as real gentlemen might do. If anything, they were likely to be unencumbered by such sentiments, uncomprehending of any social need beyond their own select circle. For them, a “gentleman” was one who sported an uncommonly polished manner and affluent lifestyle, and who presented himself as prosperous, politically conservative, and properly schooled in the art of ethnoclass supremacism.

Like most other people, Gibbon tended to perceive reality in accordance with the position he occupied in the social structure. As a gentleman scholar, he produced what elsewhere I have called “gentlemen’s history,” a genre heavily indebted to an upper-class ideological perspective.3 In 1773, we find him beginning work on his magnum opus, A History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, while settled in a comfortable town house tended by halfa-dozen servants. Being immersed in what he called the “decent luxuries,” and saturated with his own upper-class prepossession, Edward Gibbon was able to look kindly upon ancient Rome’s violently acquisitive aristocracy. He might have produced a much different history had he been a self-educated cobbler, sitting in a cold shed, writing into the wee hours after a long day of unrewarding toil. No accident that the impoverished laborer, even if literate, seldom had the agency to produce scholarly tomes. Gibbon himself was aware of the class realities behind the writing of history: “A gentleman possessed of leisure and independence, of books and talents, may be encouraged to write by the distant prospect of honor and reward: but wretched is the author, and wretched will be the work, where daily diligence is stimulated by daily hunger.”4

As one who hobnobbed with nobility, Gibbon abhorred the “wild theories of equal and boundless freedom” of the French Revolution.5 He was a firm supporter of the British empire. While serving as a member of Parliament he voted against extending liberties to the American colonies. Unsurprisingly he had no difficulty conjuring a glowing pastoral image of the Roman empire: “Domestic peace and union were the natural consequences of the moderate and comprehensive policy embraced by the Romans. … The obedience of the Roman world was uniform, voluntary, and permanent. The vanquished nations, blended into one great people, resigned the hope, nay even the wish, of resuming their independence. … The vast extent of the Roman empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of virtue and wisdom.”6 Not a word here about an empire built upon sacked towns, shattered armies, slaughtered villagers, raped women, enslaved prisoners, plundered lands, burned crops, and mercilessly overtaxed populations.

The gentlemen historians who lived during antiquity painted much the same idyllic picture, especially of Rome’s earlier epoch. The theme they repeatedly visited was of olden times as golden times, when men were more given to duty than luxury, women were chaste and unsparingly devoted to their family patriarchs, youth were ever respectful of their elders, and the common people were modest in their expectations and served valliantly in Rome’s army.7 Writing during the Late Republic, Sallust offers this fairy tale of Roman times earlier than his own: “In peace and war … virtus [valor, manliness, virtue] was held in high esteem … and avarice was a thing almost unknown. Justice and righteousness were upheld not so much by law as by natural instinct. … They governed by conferring benefits on their subjects, not by intimidation.”8

A more realistic picture of Roman imperialism comes from some of its victims. In the first century B.C., King Mithridates, driven from his land in northern Anatolia, wrote, “The Romans have constantly had the same cause, a cause of the greatest antiquity, for making war upon all nations, peoples, and kings, the insatiable desire for empire and wealth.”9 Likewise, the Caledonian chief Calgacus, speaking toward the end of the first century A.D., observed:

[Y]ou find in [the Romans] an arrogance which no reasonable submission can elude. Brigands of the world, they have exhausted the land by their indiscriminate plunder, and now they ransack the sea. The wealth of an enemy excites their cupidity, his poverty their lust of power. … Robbery, butchery, rapine, the liars call Empire; they create a desolation and call it peace. … [Our loved ones] are now being torn from us by conscription to slave in other lands. Our wives and sisters, even if they are not raped by enemy soldiers, are seduced by men who are supposed to be our friends and guests. Our goods and money are consumed by taxation; our land is stripped of its harvest to fill their granaries; our hands and limbs are crippled by building roads through forests and swamps under the lash of our oppressors. … We Britons are sold into slavery anew every day; we have to pay the purchase-price ourselves and feed our masters in addition.10

For centuries, written history was considered a patrician literary genre, much like epic and tragedy, concerned with the monumental deeds of great personages, a world in which ordinary men played no role other than nameless spear-carriers, and ordinary women not even that. Antiquity gives us numerous gentlemen chroniclers—Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides, Polybius, Cicero, Livy, Plutarch, Suetonius, Appian, Dio Cassius, Valerius Maximus, Velleius Paterculus, Josephus, and Tacitus—just about all of whom had a pronouncedly low opinion of the common people. Dio Cassius, for one, assures us that “many monarchs are the source of blessings to their subjects … whereas many who live under a democracy work innumerable evils to themselves.”11

The political biases of ancient historians were not interred with their bones. Our historical perceptions are shaped not only by our present socioeconomic status but by the ideological and class biases of the past historians upon whom we rely. As John Gager notes, it is difficult to alter our habitual ways of thinking about history because “without knowing it, we perceive the past according to paradigms first created many centuries ago.”12 And the creators of those ancient paradigms usually spoke with decidedly upper-class accents.

In sum, Gibbon’s view of history was not only that of an eighteenth-century English gentleman but of a whole line of gentlemen historians from bygone times, similarly situated in the upper strata of their respective societies. What would have made it so difficult for Gibbon to gain a critical perspective of his own ideological limitations—had he ever thought of doing so—was the fact that he kept intellectual company with like-minded scholars of yore, in that centuries-old unanimity of bias that is often mistaken for objectivity.

To be sure, there were some few observers in ancient Rome, such as the satirist Juvenal, who offer a glimpse of the empire as it really was, a system of rapacious expropriation. Addressing the proconsuls, Juvenal says: “When at last you leave to go out to govern your province, limit your anger and greed. Pity our destitute allies, whose poor bones you see sucked dry of their pith and their marrow.”13

In 1919, noted conservative economist Joseph Schumpeter presented a surprisingly critical picture of Roman imperialism, in words that might sound familiar to present-day critics of U.S. “globalism”:

… That policy which pretends to aspire to peace but unerringly generates war, the policy of continual preparation for war, the policy of meddlesome interventionism. There was no corner of the known world where some interest was not alleged to be in danger or under actual attack. If the interests were not Roman, they were those of Rome’s allies; and if Rome had no allies, then allies would be invented. When it was utterly impossible to contrive such an interest—why, then it was the national honor that had been insulted. The fight was always invested with an aura of legality. Rome was always being attacked by evil-minded neighbors, always fighting for a breathing space. The whole world was pervaded by a host of enemies, and it was manifestly Rome’s duty to guard against their indubitably aggressive designs.14

Still, the Roman empire has its twentieth-century apologists. British historian Cyril Robinson tenders the familiar image of an empire achieved stochastically, without deliberate design: “It was perhaps almost as true of Rome as of Great Britain that she acquired her world-dominion in a fit of absence of mind.”15 An imperialism without imperialists, a design of conquest devoid of human agency or forethought, such a notion applies neither to Rome nor to any other empire in history.

Despite their common class perspective, gentlemen historians do not achieve perfect accord on all issues. Gibbon himself was roundly condemned for his comments about early Christianity in the Roman empire. He was attacked as an atheist by clergy and others who believed that their religion had flourished exclusively through divine agency and in a morally flawless manner.16 Gibbon credits Christianity’s divine origin as being the primary impetus for its triumph, but he gives only a sentence or two to that notion, being more interested as a secular historian in the natural rather than supernatural causes of the church’s triumph. Furthermore, he does not hesitate to point out instances of worldly opportunism and fanatical intolerance among Christian proselytes. Some readers may find his treatment of the rise of Christianity to be not only the most controversial part of his work but also the most interesting.17

Along with his class hauteur, the gentleman scholar is likely to be a male supremacist. So Gibbon describes Emperor Severus’s second wife Julia Domna as “united to a lively imagination, a firmness of mind, and strength of judgment, seldom bestowed on her sex.”18 Historians do take note of the more notorious female perpetrators in the imperial family, such as Messalina, wife of Emperor Claudius, and Agrippina. They tell us that Agrippina grabbed the throne for her son Nero by poisoning her uncle and then her husband, the reigning Claudius. Upon becoming emperor, Nero showed his gratitude to his mother by...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Tyrannicide or Treason?

- 1. Gentlemen’s History: Empire, Class, and Patriarchy

- 2. Slaves, Proletarians, and Masters

- 3. A Republic for the Few

- 4. “Demagogues” and Death Squads

- 5. Cicero’s Witch-hunt

- 6. The Face of Caesar

- 7. “You All Did Love Him Once”

- 8. The Popularis

- 9. The Assassination

- 10. The Liberties of Power

- 11. Bread and Circuses

- Appendix: A Note on Pedantic Citations and Vexatious Names

- Notes

- Index