![]()

1

Germophobia

“Swat That Fly!”

That contemporary Americans fear food more than the French is rather ironic, for many modern food fears originated in France. It was there, in the 1870s, that the scientist Louis Pasteur transformed perceptions of illness by discovering that many serious diseases were caused by microscopic organisms called microbes, bacteria, or germs.1 This “germ theory” of disease saved innumerable lives by leading to the development of a number of vaccines and the introduction of antiseptic procedures in hospitals. However, it also fueled growing fears about what industrialization was doing to the food supply.

Of course, fear of what unseen hands might be doing to our food is natural to omnivores, but taste, sight, smell (and the occasional catastrophic experience) were usually adequate for deciding what could or could not be eaten. The germ theory, however, helped remove these decisions from the realms of sensory perception and placed them in the hands of scientists in laboratories.

By the end of the nineteenth century, these scientists were using powerful new microscopes to paint an ever more frightening picture. First, they confirmed that germs were so tiny that there was absolutely no way that they could be detected outside a laboratory. In 1895 the New York Times reported that if a quarter of a million of one kind of these pathogenic bacteria were laid side by side, they would only take up an inch of space. Eight billion of another variety could be packed into a drop of fluid. Worse, their ability to reproduce was nothing short of astounding. There was a bacillus, it said, that in only five days could multiply quickly enough to fill all the space occupied by the waters of Earth’s oceans.2

The reported dangers of ingesting germs multiplied exponentially as well. By 1900 Pasteur and his successors had shown that germs were the cause of deadly diseases such as rabies, diphtheria, and tuberculosis. They then became prime suspects in many ailments, such as cancer and smallpox, for which they were innocent. In 1902 a U.S. government scientist even claimed to have discovered that laziness was caused by germs.3 Some years later Harvey Wiley, head of the government’s Bureau of Chemistry, used the germ theory to explain why his bald head had suddenly produced a full growth of wavy hair. He had discovered, he said, that baldness was caused by germs in the scalp and had conquered it by riding around Washington, D.C., in his open car, exposing his head to the sun, which killed the germs.4

America’s doctors were initially slow to adopt the germ theory, but public health authorities accepted it quite readily.5 In the mid-nineteenth century, their movement to clean up the nation’s cities was grounded in the theory that disease was spread by invisible miasmas—noxious fumes emanating from putrefying garbage and other rotting organic matter. It was but a short step from there to accepting the notion that dirt and garbage were ideal breeding grounds for invisible germs. Indeed, for a while the two theories coexisted quite happily, for it was initially thought that bacteria flourished only in decaying and putrefying substances—the very things that produced miasmas. It was not difficult, then, to accept the idea that foul-smelling toilets, drains, and the huge piles of horse manure that lined city streets harbored dangerous bacteria instead of miasmas. Soon germs became even more frightening than miasmas. Scientists warned that they were “practically ubiquitous” and were carried to humans in dust, in dirty clothing, and especially in food and beverages.6

The idea that dirt caused disease was accepted quite easily by middle-class Americans. They had been developing a penchant for personal cleanliness since early in the nineteenth century. Intoning popular notions such as “cleanliness is next to godliness,” they had reinforced their sense of moral superiority over the “great unwashed” masses by bathing regularly and taking pride in the cleanliness of their houses. It was also embraced by the women teaching the new “domestic science” in the schools, who used it to buttress their shaky claims to be scientific. They could now teach “bacteriology in the kitchen,” which meant learning “the difference between apparent cleanliness and chemical cleanliness.”7

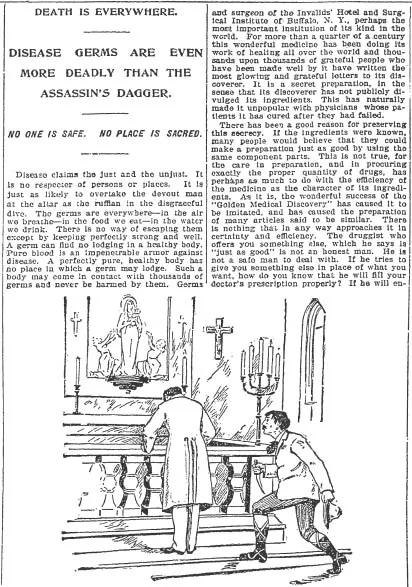

The nation’s ubiquitous hucksters popularized the germ theory by selling potions said to kill germs in the bloodstream. Even divine intervention seemed to offer no protection against these invaders. A newspaper article promoting one such potion showed an assassin about to plunge a long dagger into the back of a man praying at a church altar. The headline warned, “Death Is Everywhere. Disease Germs Are Even More Deadly than the Assassin’s Dagger. No One Is Safe. No Place Is Sacred.”8

Food and beverages were thought to be particularly dangerous because they were the main vehicles for germs entering the body. As early as 1893, domestic scientists were warning that the fresh fruits and vegetables on grocers’ shelves “quickly catch the dust of the streets, which we know is laden with germs possibly malignant.”9 A U.S. government food bulletin warned that dust was “a disease breeder” that infected food in the house and on the street.10 In 1902 sanitation officials in New York City calculated that the air in the garbage-strewn streets of the crowded, impoverished Lower East Side harbored almost 2,000 times as many bacilli as the air on wealthy East Sixty-Eighth Street and warned that these airborne germs almost certainly infected the food in the hundreds of pushcarts that lined its streets.11 The horse dung that was pulverized by vehicles on paved city streets was particularly irksome, blowing into people’s faces and homes and covering the food merchants’ outdoor displays. In 1908 a sanitation expert estimated that each year 20,000 New Yorkers died from “maladies that fly in the dust, created mainly by horse manure.”12

The notion that dirty hands could spread germs, so important in saving lives in hospital operating rooms, was of course applied to food. In 1907 the nation was riveted by the story of “Typhoid Mary” a typhoid-carrying cook who infected fifty-three people who ate her food, three of whom died. She resolutely refused to admit that she was a carrier of the disease-causing germ and was ultimately institutionalized.13 In 1912 Elie Metchnikoff, Pasteur’s successor as head of the Pasteur Institute, announced that he had discovered that gastroenteritis, which killed an estimated 10,000 children a year in France and probably more in the United States, was caused by a microorganism found in fruits, vegetables, butter, and cheese that was transmitted to infants by mothers who had failed to wash their hands with soap before handling or feeding their babies. By then, any kind of dirt was thought to be synonymous with disease. “Wherever you find filth, you find disease,” declared a prominent New York pathologist.14

New microscopes that made it easier to photograph bacteria revealed even more foods infested with germs. A ditty called “Some Little Bug Is Going to Find You” became a hit. Its first verse was

“Death Is Everywhere” reads this 1897 advertisement for a germ killer. It shows a man standing at a church altar and says: “Disease Germs Are Even More Deadly than the Assassin’s Dagger. No One Is Safe. No Place Is Sacred” (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1897)

Even house pets were caught in the dragnet. In 1912 when tests of cats’ whiskers and fur in Chicago revealed the presence of alarming numbers of bacteria, the city’s Board of Health issued a warning that cats were “extremely dangerous to humanity.” A local doctor invented a cat trap to be planted in backyards to capture and poison wayward cats. The Topeka, Kansas, Board of Health issued an order that all cats must be sheared or killed.16 The federal government refused to go that far but did warn housewives that pets carried germs to food, leaving it up to the families to decide what to do about them. What some of them did was to panic. A serious outbreak of infantile paralysis (polio) in New York City in 1916 led thousands of people to send their cats and dogs to be gassed by the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, despite the protestations of the city health commissioner that they did not carry the offending pathogen. From July 1 to July 26, over 80,000 pets were turned in for destruction, 10 percent of whom were dogs.17

But the most fearsome enemy in the war against germs was not a lovable pet, but the annoying housefly. Dr. Walter Reed’s investigations of disease among the American troops who invaded Cuba during the Spanish-American War in 1898 had famously led to the discovery that mosquitoes carried and spread the germs that caused yellow fever. But yellow fever was hardly present in the United States. Much more important was his subsequent discovery that houseflies could carry the bacteria causing typhoid to food, for that disease killed an estimated 50,000 Americans a year.18 Although Reed’s studies had shown that this could happen only when flies were practically immersed in human, not animal, excrement, his observations soon metamorphosed into the belief that during the war typhoid-carrying flies had killed more American soldiers than had the Spanish.19 This was buttressed by a kind of primitive epidemiology, wherein experts noted that typhoid peaked in the autumn, when the fly population was also at its peak.20

The number of diseases blamed on flies carrying germs to food then multiplied almost as rapidly as the creatures themselves. In 1905 the journal American Medicine warned that flies carried the tuberculosis bacillus and recommended that all food supplies be protected by screens.21 That December a public health activist accused flies of spreading tuberculosis, typhoid, and a host of other diseases. “Suppose a fly merely walks over some fruits or cooked meats exposed for sale and [infects] them,” he said. “If the food is not cooked to kill them the person who eats them is sure to have typhoid.” The New York State Entomologist pointed out that during the warm months “the abundance of flies” coincided with a steep rise in deaths from typhoid and infant stomach ailments. “Nothing but criminal indifference or inexcusable ignorance is responsible for the swarms of flies so prevalent in many public places.” A New York Times editorial agreed, saying, “It is cruelty to children to allow flies to carry death and disease wherever they go.” Flies, the paper contended, “bear into the homes and food, water, and milk supplies of the peo...