- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mechanisms of Plant Growth and Improved Productivity Modern Approaches

About this book

Discusses the mechanisms of plant productivity and the factors limiting net photosynthesis, describing techniques to isolate, characterize and manipulate specific plant genes in order to enhance productivity. The uptake of carbon and the practical aspects of plant nutrition are discussed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mechanisms of Plant Growth and Improved Productivity Modern Approaches by Amarjit Basra in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Agricultural Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Photoassimilate Transport

Wye College University of London Ashford, Kent, England

University of New England Armidale, New South Wales, Australia

PATHWAYS DEVELOPMENT AND STRUCTURE

Transport in Sieve Tubes

Evidence from bark-girdling experiments for the operation of sieve tubes predated their discovery. The roots, when detached from their supply of nutrients, died. This “ring-barking” has provided a simple yet effective method of forest clearance used since antiquity. Anatomically, however, sieve tubes are difficult to discern, even with a modern optical microscope. Also, despite the fact that it is now known that their sugary contents are under considerable positive pressure, evidence of their bleeding in response to injury was very scanty. The exceptions lay in the tropics where there was a widespread array of techniques for tapping large quantities of sap from several palms. This phenomenon was only poorly understood, however, and indeed was largely ignored in temperate latitudes where the critical questions were eventually asked about the function of sieve tubes.

The discovery of sieve tubes by the German forester, Theodore Hartig in 1837, and the subsequent observation of exudation in minute amounts from forest trees by his son, Robert Hartig, confirmed the potential role of these transport conduits. The amount of exudates, though small, was considerably greater than could flow from a single punctured sieve-tube element: hence longitudinal flow was an obvious deduction. We now understand that the sieve plates, the porosity of which has been a major cause of controversy, usually restrict the loss of sap. This is an ecological mechanism which protects plants from excessive predation by phloem-feeding animals. Though doubts persisted into the 1920s and even later, about the possible role of xylem as a possible major conductor of organic nutrients, these were progressively eliminated, e.g., by the work of Mason and Maskell [1], so that Dixon could write in 1933 [2], “It is possible to show that the movement of bast sap takes place in the sieve tubes” and go on to describe many ingenious experiments on exudation and injection. Perhaps because this paper was neglected, much of his message remained to be rediscovered in the 1970s.

It is now established beyond doubt that sieve tubes (and their numerous but tiny sieve-plate pores) transport the major quantities of elaborated nutrients within plants. All sinks (roots, fruits, buds, and secondary meristems) are supplied by the phloem sieve tubes which, therefore, collectively represent a pathway of enormous significance in the world of biology.

An interesting feature of sieve tubes is that they are laid down in close proximity to xylem conduits, which has made it difficult to distinguish between their respective roles in conduction. There may be a good reason for this situation, and it possibly reflects that sieve tubes consume and also exude considerable quantities of water from, and into, the adjacent tissues of the plant. These tissues are discussed more extensively below (see pp. 8–16).

It is known that sieve tubes originate from a series of longitudinally elongated cells (the sieve elements of the final sieve tube). The cell contents are degraded to the extent that the nucleus and tonoplast disappear, but nonetheless seem to remain “alive.” Sieve elements are partially fused at their end walls. In this region the junction wall is then locally digested to produce the characteristic “sieve plate.” This plate usually contains 50–150 pores each of which is lined with callose, a carbohydrate used in many regions of the plant as a sealant (e.g., in pollen tubes, where it helps maintain turgor). These pores can seal with callose on a seasonal basis as in temperate trees, or as a result of wounding [3]. However, on wounding the main mechanism for the sealing operation is the almost instantaneous deposition of plugs of protein in and over the pores (originally called slime; now called “P protein” for “phloem protein”). Unless special precautions are taken when microscopic sections are cut, the pores seal automatically. This phenomenon caused a long-standing controversy between anatomists, who said it was impossible for sieve tubes to function as simple open pipes, and the transport physiologists, many of whom said that they must.

Transport in Xylem Conduits

As noted above, it is quite possible for xylem conduits to transport significant quantities of photoassimilates. These long tubes are wide and water filled, when functional, and easily permeated by dissolved inorganic and organic solutes. However, on account of the direction of the transpiration stream, such a pathway for the transport of photoassimilates is of limited usefulness.

Xylem vessels are the most efficient sap transporting units, consisting of large numbers of cells fused end-to-end by perforation plates. Despite their name, perforation plates may be reduced to a mere rim with little evidence of a plate: others have rows of relatively huge pores, which may be useful in identifying wood specimens. A vessel consists of several cells linked by perforation plates. At its ends, however, sap must pass through the much more finely porous pit membranes, which act as filters, removing both suspended particles and bubbles. This gives a clue as to the major function of pit membranes, which is to prevent the spread of bubbles and thus prevent catastrophic embolization. Tracheids and fibers operate as small, short, vessels differing in that they originate from single cells. All of these units behave similarly in conducting sap, often being called collectively conduits. Although pit membranes can filter out very small particles and certain colloids, solutes in solution can pass through with relative ease.

Xylem conduits may become directly involved in long-distance transport, when they are immature. Before the walls of conduits are strengthened by lignin deposition, they are voluminous and thin walled, maintaining their shape through high turgor pressure. In this condition they strongly resemble sieve tubes, being filled with concentrated solutes, including sugars. From time to time there have been suggestions that these xylem initials may be engaged in assimilate transport, and indeed, if severed in the early spring they sometimes exude like certain sieve tubes.

Another suggestion was that these immature xylem initials might be involved in ion accumulation in roots. Through the death of the cells, the loss of membrane control would automatically release the ions into the transpiration stream, by the so-called “test-tube” hypothesis [4]. There is no firm evidence, however, that this similarity with sieve tubes is more than coincidental, arising from their mode of development, which requires vigorous cell expansion to achieve sufficiently large elements to make correspondingly large vessels. Any long-distance transport of photoassimilates in this manner seems to be insignificant.

There is, however, a major transport of organic chemicals, which are synthesized in roots, toward the aerial organs. Xylem sap has been found to convey significant quantities of organic amides and ureides in this way [5]. Another example which is very well documented, is the transportation of nicotine, an alkaloid, from the roots where it is synthesized to the leaves where it normally would protect the plant from insect predation. It is harvested by mankind to make tobacco products, which include useful insecticides [6].

Transport and Function of Rays

An important transport system in plants, which is often ignored, is the ray system. As the name suggests, rays are radial in distribution and are prominent in the medullary region: as a consequence those rays are termed medullary rays. In fact, rays extend from the medulla outwards across the cambial region into the phloem tissues where they become progressively harder to recognize in microscopic transverse sections.

Close examination of the ray cells reveals the living contents; organelles such as plastids are common, and the cells are often packed with starch or other reserve products. Between the cells are plentiful plasmodesmata giving an important clue to their physiological role. The fact that these living cells have thick cell walls in the xylem, but not the phloem, seems an essential requirement to withstand the considerable mechanical pressures that develop within growing tree trunks, which would otherwise crush the cells.

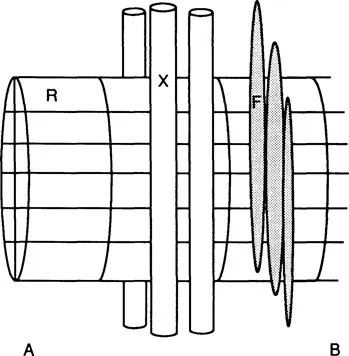

The tissue organization of rays varies from plant to plant. In longitudinal transverse section, ray cells are normally grouped into vertical ellipses (Figure 1), the size and number of cells in each group varying from species to species. This indicates that ray transport consists of a series of similar pathways connected laterally with one another, but each capable of promoting transport along the cells in a radial direction. Because the rays interconnect sieve tubes and the xylem conduits, they are in an ideal position to be able to extract or secrete solutes into the vertically oriented transpiration stream. Acer is a species which has been studied extensively in this respect [7,8,9, 10], and this work will be described here in more detail as a good example of ray and xylem transport.

Figure 1 Diagram of the way in which xylem conduits (X) and fibers (F) make contact with ray cells in wood of a tree such as Acer. The ray cells (R) run radially in groups like the spokes of a wooden wheel from the center of the tree trunk (B) toward the periphery (A).

Acer has been used for many centuries in Europe and Northern America as a source of enriched xylem sap....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Photoassimilate Transport

- 2 Plant Mineral Nutrition in Crop Production

- 3 Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation

- 4 Molecular and Applied Aspects of Nitrate Assimilation

- 5 Nutrient Deficiencies and Vegetative Growth

- 6 Growth Regulators and Crop Productivity

- 7 Impact of the Greenhouse Effect on Plant Growth and Crop Productivity

- 8 Cell and Tissue Culture for Plant Improvement

- 9 Isolation and Characterization of Plant Genes

- 10 Regulation of Plant Gene Expression at the Posttranslational Level: Applications to Genetic Engineering

- 11 The Induction of Gene Expression in Response to Pathogenic Microbes

- 12 Engineering Stress-Resistant Plants Through Biotechnological Approaches

- Index