![]()

PART I

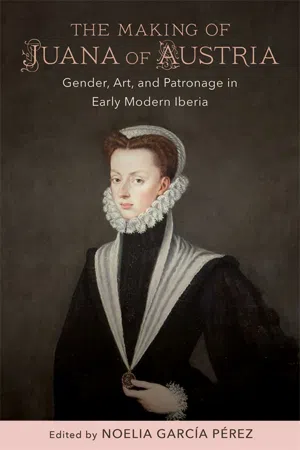

CONSTRUCTING HER IMAGE

![]()

1

WOMEN WHO RULED

Female Governance in Early Modern

Spanish Habsburg Courts

ANNE J. CRUZ

Women’s limited access to political power has been a constant throughout history. During certain periods, however, there have been notable breaks in governments typically ruled by men. One such time period occurred in sixteenth-century Europe, which stands out for the length and number of various women’s reigns. While there had been numerous women rulers in the medieval period, monarchical male power, as Theresa Earenfight affirms, was historically and ideologically privileged over women’s governance (2013, 9). Yet medieval theories opposing female rule, which continued to be advanced during the early modern period, did not impede women from governing, due in part to circumstances obliging them to accede to power during a male monarch’s absence, whether owing to war or death. Moreover, as the number of ruling women increased in early modern Europe, Sarah Gristwood has suggested the gendered nature of this rule: “The line of descent from mother to daughter runs like an artery through sixteenth-century Europe” (2016, xxviii). Indeed, two female rulers and their female relations, who would also rule—in Scotland, Marie de Guise, Mary Stuart’s regent, and in England, Mary Tudor, Catherine of Aragon’s daughter—provoked the Scottish reformer John Knox to write his infamous misogynist treatise against women’s “monstrous regime.” His blast against women rulers, based on classical and patristic writings, underscored early modern discrimination against them as much for their incapacity to govern as for their physical and intellectual weakness: “Nature I say, doth paynt them further to be weake, fraile, impacient, feble and foolishe; and experience hath declared them to be unconstant, variable, cruel and lacking the spirit of counsel and regiment” (Knox [1558] 1878, 12). Nonetheless, despite his and others’ opposition, Marie de Guise ruled Scotland for twenty years until her death, while Elizabeth I would rule England for forty-five years.

Other European countries experienced women’s rule as well, although mainly as consorts to male monarchs. In effect, the dynastic marriages of the House of Austria had opened to a number of royal women the possibility of assuming positions of political power, from governesses to empresses. The Habsburgs had a long history of deploying marriage instead of waging war in order to maintain power: for centuries, their maxim had been, “Let others fight—you, happy Austria, marry” (Patrouch 2013, 25). By doing so, the Habsburg dynasties succeeded in expanding their territories beyond their previous medieval borders and in finalizing wars, as was the case of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559). This treaty, which stipulated the marriage of Philip II to Isabel of Valois, ended the protracted struggle between France and Spain, with the former abandoning its pretensions to Italy and the Indies (Davenport 2008, 219–20). Yet conventional studies have tended to situate the women in the shadow of their fathers or husbands, assigning value to empresses, proprietary queens, and queens-consort only insofar as they met the principal objective of procreation.1 Nonetheless, while reproduction always served the purposes of dynastic formation and stability, most recently, some studies of early modern queens have highlighted women’s distinctive agency.2 In keeping with these studies, my essay proposes a gendered narrative of the multiple female rulers of early modern Spain from childhood to widowhood to shed light on their significant historical contributions. It stresses each ruler’s individual roles—both formal and informal, political and familial—as they intersected across borders through birth or marriage.

The Catholic Queen and Her Daughters

Female political power was first wielded by Isabel of Castile, who made sure to integrate her daughters through marriage into several European kingdoms. Her own rule began when she declared herself proprietary queen, not only usurping her niece’s right of succession but employing masculine symbols of power such as the sword and the Roman fasces (Weissberger 2009, 55–56). Her marriage to Fernando of Aragon reveals the gender conflicts brought about by their co-regency.3 Although Fernando always affirmed that both divine and natural law gave precedence to men, he accepted Isabel’s proclamation that Castilian law favored a legitimate daughter by direct lineage over a son through a collateral line (Weissberger 2004, 15). Monarchical rule required not only following specific courtly conduct but also developing superior intellectual and moral traits. For this purpose, the Augustinian Martín de Córdoba dedicated his conduct book, Jardín de nobles doncellas (The garden of noble maidens), to the queen in 1468, which emphasized both her legitimate rule and how she, as well as other royal women destined to be queens, should behave. While Friar Martín does not refrain from acknowledging women’s perceived weakness, he allows that they are capable of assuming power. Despite its controversial stance, in its depiction of princesses as exceptional exemplars, the text reveals a new sensitivity toward women’s education that influenced Juan Luis Vives’s De institutione feminae cristiana, the educational treatise he wrote for Mary Tudor in 1523. Isabel’s reign, therefore, looked forward to the modern world, at the beginning of the dissemination of knowledge by means of the printing press and book commerce. The world of the court would thus become one of the printed word, as shown from the impressive libraries patronized by women rulers, starting with the queen’s own (Ruiz García 2004).

Perhaps because of Isabel’s difficulties in sharing the throne with Fernando, she made sure to arrange for a humanist education for her daughters before marriage to prepare them for their rule as consorts. Although, according to Howe, her own education tended toward a medieval model, with its main concern the acquisition of virtue, the library she inherited from her father included religious, moral, devotional, and secular literary texts, such as Boccaccio’s novelle (Howe 2008, 34–35). Her interest in seeing that her children and those of the courtiers receive a humanist education led her to bring to court the Spanish humanist Antonio de Nebrija and two Italian humanist tutors, Lucio Marineo Siculo and Pietro Martire d’Anghiera, who opened a school for boys. At the same time, Lucía Medrano, Luisa Sigea, and Beatriz Galindo were commissioned to open a school for girls (Silleras-Fernández 2015, 169–70). Isabel’s efforts to learn Latin herself were perceived as exemplary for the children: according to Marineo Siculo, “the queen mother especially, although occupied with great concerns, in order to serve as an example to others, began to study the principles of grammar and hired preceptors and teachers to all in the palace, young maidens as well as pages, so all could learn” (cited in Oettel 1935, 307).

Although Isabel of Castile was not a Habsburg, she consciously imitated the Habsburg’s dictum of selectively marrying their children to form dynasties and to rule in foreign courts. Indeed, Isabel was the first in Spanish history to systematically marry each of her daughters to foreign monarchs, all of whom were eager to join the formidable House of Trastámara (1369–55) that, by the end of the fifteenth century, held first place among European dynasties (Suárez Fernández 1981, xxxviii). According to Luis Suárez F...