eBook - ePub

Justice Provocateur

Jane Tennison and Policing in Prime Suspect

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

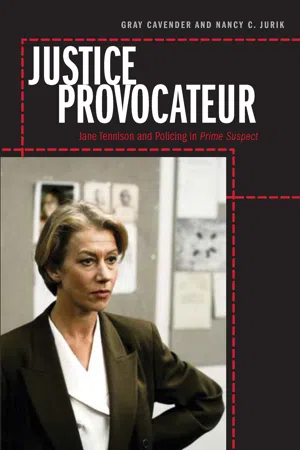

Justice Provocateur focuses on Prime Suspect, a popular British television film series starring Oscar and Emmy award-winning actress Helen Mirren as fictional London policewoman Jane Tennison. Gray Cavender and Nancy C. Jurik examine the media constructions of justice, gender, and police work in the show, exploring its progressive treatment of contemporary social problems in which women are central protagonists. They argue that the show acts as a vehicle for progressive moral fiction--fiction that gives voice to victim experiences, locates those experiences within a larger social context, transcends traditional legal definitions of justice for victims, and offers insights into ways that individuals might challenge oppressive social and organizational arrangements.

Although Prime Suspect is often seen as a uniquely progressive, feminist-inspired example within the typically more conservative, male-dominated crime genre, Cavender and Jurik also address the complexity of the films' gender politics. Consistent with some significant criticisms of the films, they identify key moments in the series when Tennison's character appears to move from a successful woman who has it all to a post-feminist stereotype of a lonely, aging career woman with no strong family or friendship ties. Shrewdly interpreting the show as an illustration of the tensions and contradictions of women's experiences and their various relations to power, Justice Provocateur provides a framework for interrogating the meanings and implications of justice, gender, and social transformation both on and off the screen.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Justice Provocateur by Gray Cavender,Nancy C. Jurik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Television History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2012Print ISBN

9780252078705, 9780252037191eBook ISBN

9780252094316CHAPTER 1

Analytic Framework

In this chapter, we develop our framework for analyzing Prime Suspect. It is our intention that this framework serve as a benchmark for examining gender and justice issues in cultural productions, including film and television. In contrast to some cultural studies approaches that claim to avoid value assessments of fictional works, we adopt an approach that not only examines but advocates for works that promote hopes for and actions toward social justice.

The first component of our framework rests on the idea that a feminist crime genre has emerged in the past few decades. As noted in the Introduction, the crime genre has historically either excluded women or presented them in subordinate and stereotypical roles. After this long, male-dominated history, the crime genre increasingly features women as producers of and protagonists in the genre. This change has altered the genre by decentering the domination of male protagonists and their methods for understanding and solving crimes. Scholars have identified other significant features of the emerging feminist crime genre: it looks beyond individuals to attend to structural roots of crime and related social problems; there tends to be less violence in such works; the protagonist demonstrates an ethic of responsibility toward victims in promoting just solutions to the case.

We drew inspiration from these discussions of a feminist crime genre to develop a second and interrelated component of our framework of analysis, a model of what we call progressive moral fiction. Some scholars have called for an increasing identification and production of factual and fictional/dramatic works that inspire others to do justice and transform unjust social arrangements. With regard to the crime genre, works of progressive moral fiction may include story lines that reveal the social systemic nature and context of criminal actions and that feature socially marginalized victims and a protagonist who understands the limitations of law and is dedicated to helping victims. We also draw on the work of other literary, feminist, and critical race theorists to formulate our ideal type model of progressive moral fiction. We will argue that our model can be used as a framework for media research and for using media to teach about gender and justice issues.

The Feminist Crime Genre

Despite a number of successful women contributors, the crime genre has been largely a male preserve. In her treatise on women detectives, Maureen Reddy (1988, 5) argues that the crime genre was characterized by disruption (the crime), linear progress toward order, the banishment of disruptive elements, and ultimately the preservation by a male authority of the bourgeois order and patriarchy. Reddy and other experts on women’s crime fiction (e.g., Munt 1994; Klein 1995) viewed the crime genre as a primarily conservative and masculine form that reinforced masculine dominance.

The first fictional British woman police detective appeared in 1864 in a book called The Female Detective. The book was “edited” by Andrew Forrester, although Kathleen Klein (1995, 18) suggests that this was a fictional work, not a police casebook. The author variously referred to the protagonist as Miss or Mrs. Gladden and denied the audience details about her life as a woman so as to focus more on her portrayal as a detective (Klein 1995, 18). A second volume featuring a woman police detective quickly followed: W. Stephens Hayward’s The Experiences of a Lady Detective. The protagonist, a Mrs. Paschal, was a widow who joined the police force because she was lacking in income (Klein 1995, 24). These two volumes generated no immediate imitators in a woman’s subgenre. Women detectives appeared later in the nineteenth century in the United States as a part of the dime novel tradition. However, Klein (1995, 24) notes that there were very few woman-centered stories and that the men writers who featured women as protagonists tended to undercut them by foregrounding romance and marriage as events that would end the woman’s role as an investigator. Thus, women appeared in the crime genre but did not alter the view that detection was a masculine pursuit (Munt 1994). There were no (or few) women investigators in the real world, so there was no believable environment for them in the crime genre (Klein 1992).

Discussions of a women’s crime genre begin with consideration of “mystery” crime novels. Famous early women mystery novelists included Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers. Agatha Christie (1890–1976) is one of the best-selling authors of all time, and her mystery series heroes included Miss Jane Marple, small English village wise woman, and Hercule Poirot, eccentric Belgian male detective. Dorothy Sayers’s (1893–1957) books featured an aristocratic amateur sleuth, Lord Peter Wimsey, who solved numerous mysteries and was especially popular in the 1930s and 1940s. Wimsey had a romantic interest in the novels, Harriet Vane, who is a mystery writer and sometimes also an amateur sleuth. She rejects Wimsey’s many marriage proposals in Sayers’s earlier novels, but they marry in Busman’s Honeymoon (1937). Christie, Sayers, and other women writers in what was initially a British literary tradition (e.g., Josephine Tey, Ngaio Marsh) were labeled as part of a “cozy” subgenre. A cozy is a mystery that contains little violence, sex, or tough language. Typically, the main character is a good, likeable woman or man who is an amateur detective and identifies the criminal through an intuitive or intellectual examination of the crime scene, suspects, and clues. At the end of the story, the criminal is apprehended, and order is restored. Cozies were usually set among the elite, often in a sedate countryside setting or vacation atmosphere, and were associated with women authors and women audiences (Walton and Jones 1999).

The hard-boiled crime novel is a different literary style that most often is associated with the urban United States and with professional detectives (and later with police) who are tough and sometimes flawed heroes. These novels include considerably more violence and sex than the novels of the cozy tradition. The beginning of this style is associated with US writers such as Carroll John Daly in the mid-1920s, but its huge increase in popularity is most often attributed to the work of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler in the 1930s and 1940s. Their stories initially appeared in pulp magazines. Even though they were later published as novels, these books are still referred to as pulp fiction. Hard-boiled detectives were almost always men. Hard-boiled authors and fans disparaged cozies as too soft and feminized (Walton and Jones 1999). Moreover, in an oft-quoted essay, Raymond Chandler offered harsh criticism of Agatha Christie and the cozy tradition for their class and cultural elitism and lack of realism (Walton and Jones 1999). He claimed that the hard-boiled tradition led by Hammett “gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse.… He put these people down on paper as they were, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used” (Chandler 1946, 222). Hard-boiled detective novels were more likely to include women characters but portray them in negative ways that we will discuss later.

Like the hard-boiled subgenre, the police procedural subgenre pioneered by another US author, Hillary Waugh (a man) (1920–2008), sought urban realism, this time through careful portrayals of routine police work. Early procedural novels largely excluded women as key characters or portrayed women in subordinated and stereotyped roles (if at all) (Hirsch 1981). Table 1.1 provides examples of each of the three crime subgenres.

Feminists have long been critical of the crime genre’s depiction of women, who, when not entirely ignored, were often relegated to the roles of victims, lovers, and temptresses. They describe how cozies, which feature women as chief protagonists, were demeaned as unrealistic or as less serious “mysteries” as opposed to more male-centered, hard-boiled, “crime” genre works. Historically, much of the hard-boiled crime genre has been so misogynistic that Klein (1995), in a play on the title of a P. D. James novel (later a British television crime series), lamented that the role of the professional detective was “an unsuitable job for a woman.”

Table 1.1. Examples of Subgenre Types

| Subgenre Types | Novels | Films or Television Series |

| Cozies | Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple series | Murder, She Wrote |

| Agatha Christie’s Poirot series | Midsomer Murders | |

| Dorothy Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey series | Nancy Drew | |

| The Hardy Boys | ||

| Hetty Wainthropp | ||

| Hard-boiled | Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade | Peter Gunn |

| Dorothy Hughes’s Dix Steele | Mannix | |

| Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe | Chinatown | |

| Margaret Millar’s Tom Aragon | Veronica Mars | |

| Police procedural | Ed McBain’s 57th Precinct series | Dragnet |

| John Creasey’s West Scotland Yard series | Hill Street Blues | |

| Joseph Wambaugh’s novels about the LAPD | The Bill | |

| Lynda La Plante’s police novels | The Sweeney | |

| Elizabeth George’s Inspector Lynley series | The Gentle Touch | |

| Juliet Bravo | ||

| Cagney & Lacey | ||

| NYPD Blue |

Despite its male-dominated history, a few women writers (e.g., Dorothy B. Hughes and Vera Caspary) did gain some success in the hard-boiled tradition during the 1930s and 1940s. Their now-classic novels, Hughes’s In a Lonely Place (1947) and Caspary’s Laura (1943), also became successful films. These writers influenced other hard-boiled and suspense novelists, several of whom were also women. For example, Elizabeth Sanxay Holding (1889–1955) was described by Raymond Chandler as one of the top writers of detective and suspense fiction. Margaret Millar (1915–94), who has been recognized for her intelligent portrayals of women’s psyches, dealt with issues of sexual freedom, madness, and hypocritical moral codes that were shaped by class position. One of her protagonists was a Latino lawyer named Tom Aragon. In contrast to much other hard-boiled fiction, these novelists featured women in strong roles, although not as police officers or professional detectives. When their novels featured investigators, these roles were generally occupied by men.

The number of crime novels written by women began to sharply increase in the late 1970s, and the upward slope of that increase became even more pronounced in the 1980s and 1990s (Klein 1992; Walton and Jones 1999). Although not all of these novels featured women investigators, the number of crime novels with women protagonists exploded in the mid-1980s and has tripled every five years since 1985 (Mizejewski 2004, 19). A by-product of the growth in women’s crime fiction has been the appearance of numerous scholarly treatises on women’s crime fiction (see Reddy 1988; Munt 1994; Klein 1995; Walton and Jones 1999).

Dorie Klein (1992) and others (e.g., Klein 1995; Reddy 1988, 2003; Walton and Jones 1999; Mizejewski 2004) who analyze women’s crime fiction agree that such works exhibit features that distinguish them from the traditional male-centered crime genre. These works offer images of strong and independent investigators in a variety of settings such as private detectives, police homicide detectives, FBI agents, and forensic pathologists. These novels also deal with women’s experiences of workplace discrimination and victimization (Walton and Jones 1999). Plots tend to feature crimes that are linked to social problems or to the larger social structure; indeed, Klein (1995) notes that, unlike more traditional male-centered works, social disruption, not crime, often drives these stories. Unlike much of the traditional crime genre, women detectives are not appendages to men; they may be single, have a support group of other women, or be involved in lesbian relationships (e.g., Katherine Forrest’s Kate Delafield novels and Laurie King’s Kate Martinelli series). Several sources (e.g., Klein 1992; Klein 1995) suggest that there is less violence in the feminist crime genre and that if violence occurs, it is less glorified and less sensationalized, and the depictions convey the negative outcomes of violent acts. Klein (1995) and Mizejewski (2004) conclude that where men detectives answer to an internal moral code, women detectives, in line with arguments of scholars such as Carol Gilligan (1982), are driven by an ethic of social responsibility and compassion toward victims. Feminist crime fiction confronts issues of sexual orientation, class bias, corporate corruption, and racism.

Barbara Neely has developed a series of crime novels focused on amateur detective Blanche White, who is an African American woman working as a maid (the novels are set in New England and the southern United States). Because she is a domestic worker and a woman of color, Blanche and her domestic worker colleagues are often treated as invisible by other white and more elite members of society, including police and professional detectives. As a result of this marginalized status and her keen observational and deductive skills, Blanche is able to see, hear, and know things that go unheard or unobserved by others. The novels present captivating mysteries that simultaneously result in a solution to the crime but also a better understanding of racism and the limits of law in a racist society.

Women appeared as police officers in television crime dramas about the same time that women entered police patrol work in greater numbers. They were cast in ensembles and in a few starring roles (e.g., Police Woman in the 1970s and The Gentle Touch in the 1980s). Given women’s real-world occupational changes, institutionalized sexism was an available plot device in these police programs (Mizejewski 2004). This shift in procedurals occurred amidst a trend toward women-centered programming in television more generally (Walton and Jones 1999; Mizejewski 2004). By the 2000s, the television crime genre increasingly featured strong, independent women investigators in a variety of settings such as street cops and police homicide detectives.

The relatively greater presence of women in television programming when compared to that of film is related to both the proportionate size of women television audiences and the lower costs of television productions. These factors converge to make television producers more willing to experiment with women characters and women’s issues (Rapping 1992; Mizejewski 2004).

Even procedurals that feature women protagonists are often trapped by male-centered conventions. These productions typically adopt a liberal, equal opportunity kind of feminism and do not intend to fundamentally alter the genre. Nevertheless, several scholars argue that casting women in central roles goes well beyond producer intent and control (Walton and Jones 1999; Johnston 1999). Women detectives are not merely substitutes for men; their presence literally changes the genre and produces critiques of such important dimensions of the formula as the nature of authority, which no longer remains a male preserve, and the form of justice provided by the criminal justice system. These productions give women a greater sense of agency and resistance and promote a deeper sense of justice than law alone provides. Genres change with the times (Mittell 2004), but some argue that feminism changed the crime genre to such an extent that it comprises an entirely new form (Reddy 1988; Klein 1995; Sydney-Smith 2009). Dorie Klein (1992) utilizes the label—a feminist crime genre—to refer to novels, but we expand the usage of her term to include women-centered television and film productions.

Most feminist critiques of the crime genre focus their attention on women’s infiltration and deconstruction of more hard-boiled works and thereby understate the accomplishments and continued importance of women-centered elements within the cozy tradition. These critiques also tend to overlook the possibility for blending the so-called feminine cozy with masculinist hard-boiled traditions. For example, Lidia Curti (1988) discusses blends of feminine-associated soap opera plots and narrative styles with more masculine police procedural–style narratives in 1980s police dramas such as Hill Street Blues, Juliet Bravo, The Gentle Touch, and Cagney & Lacey. As noted in the Introduction, these procedurals combined the police procedural genre with subplots about the personal lives and conflicts of series characters. Curti (1988) also notes that they combine a linear with a circular narrative style. Th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Analytic Framework

- 2. Prime Suspect and Women in Policing

- 3. Investigating and Challenging

- 4. Doing Justice

- 5. Private Troubles and Public Issues

- 6. Prime Suspect and Progressive Moral Fiction

- Appendix: Prime Suspect Episode Overview

- References

- Index