eBook - ePub

Hungry for Revolution

The Politics of Food and the Making of Modern Chile

- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

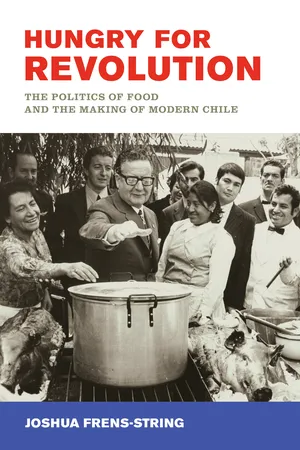

Hungry for Revolution tells the story of how struggles over food fueled the rise and fall of Chile's Popular Unity coalition and one of Latin America's most expansive social welfare states. Reconstructing ties among workers, consumers, scientists, and the state, Joshua Frens-String explores how Chileans across generations sought to center food security as a right of citizenship. In so doing, he deftly untangles the relationship between two of twentieth-century Chile's most significant political and economic processes: the fight of an emergent urban working class to gain reliable access to nutrient-rich foodstuffs and the state's efforts to modernize its underproducing agricultural countryside.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hungry for Revolution by Joshua Frens-String in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

A Hungry Nation

ONE

Worlds of Abundance, Worlds of Scarcity

AFTER SEVERAL MONTHS working the mineral-rich nitrate plains, Juan Chacón arrived back in Santiago as the First World War wound down, discovering a city brimming with both social discontent and political possibility. Speaking to his biographer some four decades later, the longtime Chilean Communist Party (PCCh) activist remembered how in those years global demands for equality and democracy reverberated throughout the city’s working-class districts. “The Russian Revolution brought the most heated debates and discussions,” Chacón recalled. “We devoured the press which reported every day on how the revolution was advancing, how it was stalling, how it was moving backward, and then how it advanced again.”1

What proved especially intriguing to Chacón, however, was the way the organizers of those demonstrations—mostly students and workers—tied their support for the Soviet revolution to local campaigns against high rents and unjust evictions and for better salaries, what the leftist called “our own struggle against the rising cost of living.” In this respect, a gathering organized by the AOAN, a labor-based organization committed to capping food prices, left a particularly lasting impression. Chacón recollected how, as one public meeting to discuss inflation and food scarcity concluded, attendees broke out into a spirited rendition of “The Internationale.”2

The early decades of the twentieth century represented a significant conjuncture for poor and working-class Chileans like Chacón. As livelihoods and work opportunities became ever more tied to global circuits of trade and foreign investment, Chile experienced some of its most sustained years of economic prosperity to date at the turn of the century. And yet as the early lives of Chacón and his political contemporaries demonstrated, the beginning of a new century was also plagued with deepening social inequities. With each passing year, workers and their political allies saw ever more clearly how the economic growth of the era was being built upon the backs of the excluded.

Centered around the early years of the twentieth century, this chapter maps the rise of these two contrasting phenomena in Chile: economic prosperity on the one hand, and economic marginalization on the other. Following the movement of money, people, and political ideas between the country’s urbanizing capital city, Santiago, and the export-oriented mining regions of the Chilean North, the chapter examines how food came to shape Chile’s place within the global economy while simultaneously becoming a defining feature of the exploitation and exclusion that urban workers and their families faced on a daily basis. By exploring when and why inequitable access to basic consumer essentials became commensurate with what reformers of the era dubbed the “social question,” the chapter also illustrates how popular organizing around food insecurity set the stage for the emergence of mass politics in Chile and a vision of what a more just national economy might look like.

LIVING IN A LAND OF PLENTY

An observer arriving in Santiago around the turn of the twentieth century would have undoubtedly been struck by a city replete with markers of modernity. Telephones, electric streetlights, paved streets, and electric trams all appeared in the capital’s city center in those years. At the same time, larger infrastructure projects were quickly reshaping the city’s physical landscape, turning Santiago into a model of urban progress in South America. The historian-turned-politician Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna jump-started a first wave of modernization in the late 1870s and early 1880s. As governor of Santiago province, Vicuña Mackenna channeled state revenue gained from commodity export duties toward the re-creation of the capital’s urban geography. Vicuña Mackenna was credited, for example, with turning Cerro Santa Lucía, site of the city’s 1540 founding, into one of the continent’s most attractive public parks. He also promoted the construction of the tree-lined Alameda as the city’s main east-west artery and poured unprecedented amounts of public capital into large-scale building projects.3

By the late nineteenth century, state and municipal officials had built upon Vicuña Mackenna’s initiatives by completing the construction of a new central market, municipal theater, and congress building. The expansion of the small Mapocho River into a canal that, according to some, resembled Italy’s Tiber or Central Europe’s Elbe, followed, as did the establishment of a narrow, meandering greenbelt, known as the Parque Forestal, along the Mapocho’s southern banks.4 In 1897, the city’s central train station, designed by French architects, was rebuilt, streamlining the movement of goods and people between Santiago, the country’s rural countryside, and its chief port cities. As further evidence of Chile’s urban development, by 1903 some 275 streetcars crisscrossed the capital city, linking together new neighborhoods to the north, south, and west of Santiago’s city center.5 Santiago may not have had the sophisticated architecture or culture of the Argentine capital, Buenos Aires, one eyewitness noted at the turn of the century, but it had certainly distinguished itself from the capital cities of its other Latin American neighbors.6

A high-powered coterie of bankers, large landowners, foreign merchants, and industrialists were among those who took up residence in metropolitan Santiago during this period, their evolving consumption habits becoming a symbol of Chile’s newfound prosperity.7 Between 1875 and 1903, annual wine consumption in the country more than tripled, from 81 million liters to 275 million liters, a result of bountiful supplies of European imports.8 Similarly, increases in beef consumption suggested a country in the throes of transformation. By the end of the 1880s, per capita beef consumption in Santiago reached almost 150 kilograms of beef per year, a figure that was roughly double the average amount of red meat consumed by residents of New York or Paris at the time and nearly three times the national average in England.9

Amid these changes, the demographic character of Chile also evolved. According to historian Arnold J. Bauer, by the late nineteenth century, “every landowner who could afford it” had built a second home in the Chilean capital and was spending more and more time away from his country estate.10 New job opportunities for rural people of modest means, particularly poor women who flocked to the city to work as domestics, cooks, and laundresses for the country’s political and economic elite, accompanied the process of spatial centralization. As a result, the population of the department of Santiago, a geographic unit that included two dozen parishes of different sizes and at various stages of urbanization, more than tripled in the four and a half decades between 1885 and 1930. Whereas the population of the department was scarcely 11 percent of Chile’s total population in 1885, forty-five years later Santiago constituted nearly a fifth of the country.11

As was the case throughout turn-of-the-century Latin America, the driving economic force behind the urbanization and geographic centralization of Chile did not lie in the dynamism of the country’s capital. Rather, urban development was fundamentally shaped by—and frequently dependent upon—Santiago’s intimate and inescapable relationship to the political economy of raw material extraction.12 As midcentury demand for Chile’s agricultural imports subsided, mineral exports became the primary fuel of national economic growth. In this respect, no part of Chile’s national territory was more critical to the growth of cities like Santiago than Tarapacá and Antofagasta, the country’s two most northern provinces, which together represented the unsuspecting wellspring of the global agricultural economy.

TABLE 1 Urban Growth in Late Nineteenth-and Early Twentieth-Century Chile

Known simply as the Norte Grande, the mining regions of Tarapacá and Antofagasta were home to the world’s largest deposits of saltpeter, a sodium-nitrate compound that, when processed down into a soluble, crystalline fertilizing agent, restored agrarian vitality to fruit, vegetable, and grain fields in Europe, the United States, and beyond. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, the Chilean military had waged an aggressive war to annex the resource-rich Atacama Desert from its neighbors to the north and east, Peru and Bolivia. With the Norte Grande under Chile’s full sovereign control beginning in 1884, extraction of nitrates from its arid plains, or pampa, proceeded apace, soon succeeding Peruvian guano as the fertilizer of choice for agriculturalists around much of the world.13 Estimates suggest that annual global exports of Chilean nitrates surpassed one million tons around 1890. During the first decade of the twentieth century, that figure surged over the two-million-ton mark. By 1913, just one year before the First World War began, Chilean nitrate sales abroad hit a record 2.75 million tons per year, thus constituting 80 percent of the country’s total exports and approximately 50 percent of all ordinary public revenue in Chile.14

Nevertheless, throughout the nitrate era—a period that most see as beginning with the War of the Pacific (1879–83) and ending with the global economic crisis of the early 1930s—Chile’s control over its most important economic sector remained circumscribed. For the first three decades of the twentieth century, foreign investors and engineers followed the demands of foreign agricultural consumers in developing the industry. By extension, foreign interests directed Chile’s national economic trajectory as well. At the end of the 1880s, Great Britain was the dominant player in the Chilean nitrate trade as British capitalists secured effective control of production at a plurality of the nitrate oficinas (processing centers) that dotted the Chilean desert highlands.15

Nitrate baron John Thomas North was the most recognizable face of British economic influence on the pampa. A shrewd and demanding businessman, North is credited by scholars with successfully reducing the cost and increasing the scale and intensity of nitrate production in late nineteenth-century Chile. However, the economic power of the “Nitrate King,” as North became known, also provoked resentment. By the late nineteenth century, North claimed a controlling stake in almost every facet of the region’s development, operating shipping lines and railway networks as well as enterprises that provided potable water, electricity, and basic foodstuffs to the region.16

The work of international marketing agents bolstered the intensity of extraction by foreign investors like North. In fact, even more than European and later North American capitalists, those who served as foreign distribution agents for Chilean-made nitrate fertilizers were responsible for turning the South American country into an axis around which an ever-more-globalized food economy turned. Or at least that was how many sought to portray themselves. In preparation for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, the London-based Permanent Nitrate Committee, a marketing company run by a conglomeration of prominent nitrate producers, printed and distributed half a million pamphlets detailing the indispensability of nitrate fertilizers to the international agricultural economy.17 A few years later, in 1899, a group of US-based nitrate agents embarked on a roughly twelve-thousand-mile, sixteen-state tour of the United States and western Canada to promote Chile’s “all-natural” fertilizer to North American farmers, the editors of popular agricultural publications, and fertilizer retailers.18 “A portion of our earth, namely Chile, has by accident or by design been set aside as a storehouse for nitrogen in its most available plant food form,” William S. Myers, the longtime head of Chile’s nitrate marketing operations for the New York–based Chilean Nitrate of Soda Educational Bureau, declared in a speech presented to a group of US businessmen in the early 1900s. As he touted the future prospects of Chile’s most important industry, Myers, a chemist by training, added that nitrates—an “All-America product,” in his words—provided US farmers with “first aid and continued nourishment” against the sort of soil depletion that was decimating Chilean agriculture.19

Marketing agents played a particularly decisive role in demonstrating to US farmers that a deep ecological interdependence bound North American agriculture to Chilean mineral extraction. In one 1910 memo, the New York office of the Educational Bureau wrote proudly that there was no doubt that an “enormous increase” in nitrate use in the United States was due to the “missionary work” of nitrate advertising specialists. There was “hardly an issue of any farm paper today which does not have some reference somewhere in its pages” to the agricultural importance of Chilean nitrate of soda fertilizer, the memo maintained.20

Nearly a decade and a half later, and shortly after US president Calvin Coolidge warned that the United States should prepare itself to become a food-importing nation, nitrate industry officials in New York underscored the then president’s “repeated references” to US overreliance on fertilizers to meet its domestic food needs.21 “Foremost amo...

Table of contents

- Imprint

- Subvention

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Building a Revolutionary Appetite

- Part One. A Hungry Nation

- Part Two. Containing Hunger

- Part Three. Recipes for Change

- Epilogue: Counterrevolution at the Market

- Key Acronyms and Terms in Chilean Food History

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index