eBook - ePub

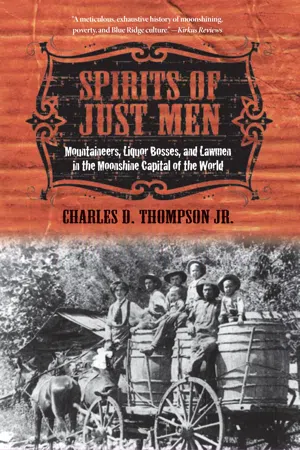

Spirits of Just Men

Mountaineers, Liquor Bosses, and Lawmen in the Moonshine Capital of the World

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Spirits of Just Men

Mountaineers, Liquor Bosses, and Lawmen in the Moonshine Capital of the World

About this book

Spirits of Just Men tells the story of moonshine in 1930s America, as seen through the remarkable location of Franklin County, Virginia, a place that many still refer to as the "moonshine capital of the world." Charles D. Thompson Jr. chronicles the Great Moonshine Conspiracy Trial of 1935, which made national news and exposed the far-reaching and pervasive tendrils of Appalachia's local moonshine economy. Thompson, whose ancestors were involved in the area's moonshine trade and trial as well as local law enforcement, uses the event as a stepping-off point to explore Blue Ridge Mountain culture, economy, and political engagement in the 1930s. Drawing from extensive oral histories and local archival material, he illustrates how the moonshine trade was a rational and savvy choice for struggling farmers and community members during the Great Depression.

Local characters come alive through this richly colorful narrative, including the stories of Miss Ora Harrison, a key witness for the defense and an Episcopalian missionary to the region, and Elder Goode Hash, an itinerant Primitive Baptist preacher and juror in a related murder trial. Considering the complex interactions of religion, economics, local history, Appalachian culture, and immigration, Thompson's sensitive analysis examines the people and processes involved in turning a basic agricultural commodity into such a sought-after and essentially American spirit.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Spirits of Just Men by Charles D. Thompson Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2011Print ISBN

9780252078088, 9780252035128eBook ISBN

97802520952691

Conspiracy Trial in the Moonshine Capital of the World

Government had long been to them a thing far off. They got no benefit from it. Roads were poor and there were always government men interfering. They sent men in to stop their liquor making. They wanted to collect taxes. For what? —SHERWOOD ANDERSON, Kit Brandon

IN 1934, THE ROAD UP Thompson Ridge was red dirt or mud, depending on the weather. No road grader or state gravel had ever touched it. After a rain or snow, people parked their roadsters or trucks, the few who had them, that is, at the foot of the hill and walked home. Sometimes they used their teams of horses or mules to pull the stuck vehicles up the hill to their farms. Sometimes they just left them at the bottom of the hill by the store until the road dried out.

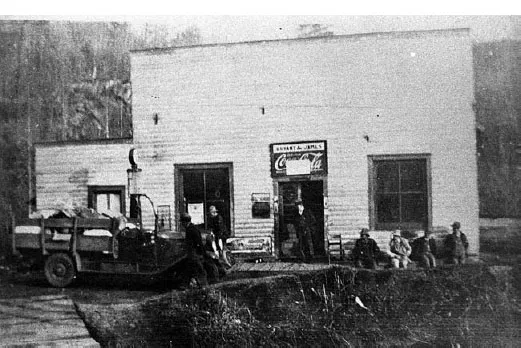

Pete Thompson's store sat at the foot of that hill on level ground where two different roads intersected, one that wound back out to Long Branch Church and the other that wended toward Ferrum the back way. It was a good location for conducting local commerce. There were other stores in the broader community of Endicott then, including the Bryant and James store that housed the post office and was the center of the community a few miles away, but Thompson's was that hollow's store, and people went to it in part because it was too hard to go anywhere else. For some it was also a decent place to get the essential ingredients they needed for making whiskey without having to let too many know their business. Old Man Thompson didn't keep written records, at least ones just anybody could access, and he didn't talk about others' dealings. Keeping quiet was part of surviving, economically and otherwise, particularly for store owners, who couldn't help but hear or overhear news and gossip.

In good weather, the store's front porch was a gathering place. In winter, people moved in around the stove. Little stores like Thompson's were places to buy maybe a strawberry soda or a can of potted meat and some crackers and sit and talk about the weather and maybe intimate just a little of their predicaments to a neighbor struggling in the economic bottom we now call the Great Depression. Few would reveal much, particularly about the businesses that kept Pete Thompson's store in the black. More than a few barns had been burned down after someone said too much to the wrong man. But people who knew each other well did hint around and gave each other clues. Sometimes people have to talk—at least among people they think they can trust. A boiling pot, even of the best copper, has to give off steam or it will explode. Indeed, sometimes there had been explosions and there would be more.

If we squint, we can see the men sitting at the store in their patched overalls, cracked brogan shoes, hats with salt lines dried on their crowns, maybe one of the men whittling an oak stick, making curled shavings that fall at his feet, maybe another spitting tobacco juice every so often, each of them knowing the folds of the hills surrounding them nearly as well as the lines of their own hands, but none of them having a firm hold on their livelihoods. At least they found some solace, and pleasure, in sitting together for a spell. They farmed the same crops: corn, potatoes, beans, apples, and tomatoes, to name the most common. Almost every one of them raised hogs and milked a cow or two and shared the same weather as their neighbors, and this common work and experience would start and end most conversations. But every so often, talk turned more serious, to themes of their common plight: too little income and too little land and what they were trying to do about it. But few let on much about their pain. Even when they did speak a few details about their worries or plans, it was often in the form of a joke or in hushed talk or with encoded words we might not understand at first. This was especially true for men engaged in the illegal business they called blockading.

Though there is no store there today, and not one business anywhere near now, dozens of upturned flagstones along with a few granite markers lined up in family cemeteries up on the ridges, the overgrown farmsteads surrounded by zigzagged chestnut rails slowly rotting into soil, the metal and wood parts of old stills now rusted and rotten along creek beds, and the ruins of the store with a rusted Nehi sign all show that people once lived, worked, conducted business, and died near there. It is remarkable how many hundreds of them did given how quiet the ridges and hollows seem today. If we strain to hear them, their voices echo from the oral histories of their kin, the words still passed along in conversations at the car lot or the feed store or from the ruins of the places themselves.

FIGURE 6. Bryant and James Store and the Endicott post office, circa 1915. Author's personal collection.

Farmers talked about the weather, as farmers will always do. In the summer of 1934, there was too much rain. Some of them had never seen so much water: Just when a man's trying to get his hay cut and put up! My corn's laid over by that wind, and I don't know if it will ever stand up again. And on top of that, I'm supposed to have a load of you know what ready to haul out. Them lawmen is breathing down my neck, and don't they know I've done bought plenty of sugar on credit here and I need to make a dollar same as anybody else? Loads of sugar coming this way from down at Ferrum Mercantile is like gold—all them store owners buying it up and prices going higher. Hard to say how many thousands of pounds of malt and everything they're unloading down there at the train depot. Somebody's making a killing, but it sure ain't me or any farmer I know.

There was talk among kin, and some of Pete's customers were his kin. Every now and then anger would make them say more than they planned: You got to pay for the things and pay to send it out the other direction, too. They complained about getting caught up in the mess. I wish to God I'd never seen that lawman Jeff Richards coming toward my place. Twenty-five dollars just to run a batch! Now I feel like a duck shut up in a pen, nowhere to run or fly, just scooping up grain and fattening up for the slaughter. I dog if it's worth it, but what else can you do, sit there and starve? I guess you could get deputized like old Luther Smith done and start getting paid to go after the bootleggers. I heard he quit them crooks, though.

What about you, Pete? They turned to the crotchety man with his elbows propped on the counter. You're sitting here at the store getting rich, ain't you? It was a common joke as everyone knew no one was. But among his most trusted friends, he would've talked back a little, mentioning the racket all of them were caught in.

Hell you say, boys! What if them federal lawmen start cracking down on the sellers? And you're forgetting one thing. I'm using some of the cans and sugar, too. I'm in it with you. And if one of us goes down, we all probably will. And people are talking. What about sheriffs and hotshots taking money from the little man? Don't the federal government think about that? But don't you know if they get to pushing, it's the little man's that's going to pay?

When they thought it really safe, Carter Lee's, the commonwealth attorney's, name came up. A few jokes circulated about so-called law. Somebody's wealth all right, but it sure ain't common, one of them said. Lord knows they run them caps and worms out the back door of the courthouse to a bootlegger as fast as the deputies bring them in the front. And I've paid them big men near as much as I've brought in. I just wonder how long it can last. Too many's got into it. And the big ones has got too big.

We folks here don't know the half of how much they're making off us. They've got it running up to Washington, even Chicago. They've got it going down south. Our county's the hub of something big. Them runners heading to Roanoke and Winston are just the start of it. We sure ain't ever been on the map before, but we sure are starting to look like a mighty big part of this here business. It can't last like this, boys. Something's bound to change.

The neighbor men would sit awhile, everyone knowing that they were playing with fire. A few would load up some bags of sugar. Some could pay cash after a run and some couldn't but instead would buy on credit until the still was run. After visiting a bit, some procured square-sided five-gallon cans and loaded them onto a truck bed and covered them with a canvas tarp. But they weren't hiding much from those who lived there. Everybody knew everybody's business. This was protection and vulnerability sewn into one backdrop.

Even the children knew, but they were told to keep away from the places back in the hollows where the men gathered during the night, lanterns burning and steam rising up through rhododendron and hemlock branches, unless they were needed to help. Everyone could tell a still was running, sometimes by the thumping sound or the smoke or when the hogs and cattle coming upon spent mash would stumble around fields or when the men gone to drink would walk the roads staggering, too. The children of the mean drunks knew especially well. Sometimes people could tell by a man's extra money he spent at the store when a run was done.

The most serious of the liquor makers either refrained from drinking while working or kept away from it altogether. There was too much at stake to run a still while under the influence. They knew that some of those around them had done time. Being sent to jail meant even less money for the family. So they set up a network for notifying people that when alerted spread faster than a car could drive. Stillers usually knew that the law was coming to make a bust perhaps an hour or more before they arrived. There was a system of warnings: might have been a series of shots or shouts, a farm bell or a child running down a path to a neighbor's homestead, or notices relayed from as far away as Ferrum that told of strange cars or people headed their way. The whole community, regardless of age, worked together to protect this livelihood, even if they didn't do the work itself. They knew why their men and women had to make liquor; it was no less a necessity than having to get up on dark winter mornings to break ice out of springs or to feed and milk the cows. Turning corn into liquor was a farm chore, and just about the only one that yielded cash in that time and place.

A few outsiders who used the old red road caused no alarms when they did so. Two of them were Miss Ora and Miss Maude, the women missionaries who lived up at St. John's on the other end of the community, in what the local people called the Rock Church. The two sometimes made their way in the mission's car up into the back hollows to tend to the sick and to women giving birth, walking or riding horseback if they had to and arriving in the homes with baskets in hand and with mud-caked shoes. The granny midwives were often the first to arrive for birthings, but the missionaries were usually close behind and welcomed when they made it. They had medicine and later even visiting doctors who worked with them. Another frequent visitor in the early years, the most regular of all when he carried the mail in his horse-drawn jumper, was the Primitive Baptist preacher named James Goode Hash. Most called him affectionately Elder Goode, as he befriended and tried to help most everyone in Endicott and neighboring communities for miles around, sometimes catching a ride with relatives or neighbors and going on foot to make his rounds. He was often the preacher called on to talk with the sick and dying, read them the Bible, and help bury those who succumbed. Besides those few, and the occasional musicians who would come through to play a house dance, most everyone who came through on horseback, in wagons, or in motor vehicles lived there.

That is, except for the bootleggers from out of county and even out of state, like the Duling boys from West Virginia, and other buyers that people didn't know at all, who started showing up in the dead of night to pick up a load, or convoys of drivers from outside the community, from places like Floyd and Roanoke, came roaring in unannounced and left out at speeds too fast for most drivers on a dirt road. Then there were the lawmen who barreled into the community, sometimes two or three carloads at a time, guns readied, in an attempt to surprise some unsuspecting crew at their stills, as well as the other lawmen there to collect fees for protection from busts.

With the community's warning systems at the ready and informants as far away as Ferrum calling in once phones came, few raids or even visits occurred without prior knowledge. But as traffic on even the worst roads increased and unknown vehicles went there for business or to try to break it up, people lost their ability to know every car owner and to name who went up or down the road. The Endicott roads, as bad as they were, became busy with commerce and its regulation, even if most of the dollars traveling them were destined for pockets elsewhere, including the pockets of the lawmen themselves. The traffic was a clear sign that change had come, and the cars were harbingers of a world of consequences about to break in on Franklin County with full force.

In January 1934, Federal Agent Col. Thomas Bailey, a decorated World War I veteran, drove alone into Franklin County, Virginia, where Endicott is located, to work undercover. While serving in the 111th Infantry in France, Bailey, then a lieutenant, crawled on his belly a hundred yards through a no-man's-land of trenches and barbed wire. He then sneaked another two hundred yards behind German lines, gaining what his Distinguished Service Cross citation called, “Information of the greatest value, making possible a subsequent and successful attack.”1 Bailey also won medals as a sharpshooter. Some two decades later, at the height of the Great Depression, the territory Bailey penetrated was domestic. This time the colonel's orders came from the Alcohol Tax Unit of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. His assignment was to infiltrate and prosecute perhaps the biggest hot spot of moonshine production in the Virginia Blue Ridge. He had no idea when he set out just how hot it would be.

Prohibition had ended in March 1933, ten months prior to Bailey's arrival. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Twenty-first Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only two weeks after his inauguration, repealing the Eighteenth Amendment, or the Volstead Act, that had made the manufacture, sale, and distribution of alcohol illegal. The Eighteenth, which had passed in 1919, was the only amendment to ever be repealed. The reversal brought to an end the harrowing work of the Bureau of Prohibition, made famous by Agent Eliot Ness and the Untouchables. But the repeal did nothing to lessen the government's interest in ending illegal alcohol production. Instead, the government's tax collection responsibilities intensified.

By 1934, licensed breweries and distilleries, mostly well-financed larger businesses, were beginning to make a comeback in some parts of the country and starting to pay their taxes, just as the Tax Unit wanted them to do. Yet, with illegal distribution channels already well entrenched, underground alcohol continued to flow, particularly from places where jobs were scarce. With unemployment running higher than 25 percent nationally at that time, and with some areas like the Blue Ridge much higher, jobs off the farm were scarce as hens' teeth. On top of that, for broke consumers who needed a drink, alcohol made and sold without the hefty taxes added by the state and federal governments was several dollars cheaper per quart. And likely just as important, homemade liquor had a loyal following that was hard to break, particularly among those who had little access to government Alcoholic Beverage Control stores: people living in dry communities and residents of poor communities from the West Virginia coalfields to the Philadelphia inner city. Once people had gotten used to white liquor, the store-bought stuff just didn't have the zing.

Thus the Treasury Department had a nearly impossible assignment just one year after Prohibition's repeal. Though the Tax Unit agents' job was no longer the idealistic effort to put an end to alcohol consumption as Bailey's forerunners had attempted, they still had to catch people avoiding taxes on alcohol and, through stamping out illegal operations, attempt to systematically direct people to legal production and consumption. They were revenuers, tax men, and their mandate was to help clear up corruption and to bring in funds to help run a strapped government. Since the Whiskey Rebellion of George Washington's day, taxes on liquor had been a matter of life and death. This assignment was not for a bureaucrat; a military spy was perfect.

By the time of Bailey's arrival, Franklin County's reputation had already gone national. Even by the 1920s, tales of fast liquor running and moonshine blockades in the Virginia mountains had reached the press, and myths about the place abounded. Some of the gullible believed every single inhabitant, regardless of age or gender, was involved. Rumors spread about armed hillbillies ready to blow your brains out if you got lost and veered too close to a still. Starting at the turn of the century, a whole literature had sprung up about Appalachian mountain life, and as the nation read the exaggerated stories, mesmerized by people living as pioneers of old, misinformation about mountain lawlessness and depravity metastasized. Things got even more ridiculous as comics in print and on radio caricatured the Snuffy Smiths of the hills, men with an aversion to work and with a gun in one hand and a jug in the other. Even people from the county seat of Rocky Mount were afraid to venture into the mountains in their own county, adding further to the problem of neglect of roads and schools in the region. No one had stopped to think of providing economic aid to mountain farmers, alternative jobs, or even that perhaps legalizing the small-scale stills could be a means of curtailing illegal trafficking.

While exaggerations abounded about the people and how they lived, one amazing statistic was true: Millions of gallons of whiskey were being produced and sold out of Franklin County every year. This truth intermingled with overblown reputations and lies, locally and all the way to Washington's Treasury Department. Thus Franklin County showed up on the federal radar and, with the agent's arrival, would become the first big example Bailey's department used to teach others throughout the Blue Ridge a lesson.

As for the boys down at Pete Thompson's store and the many small-timers in Franklin County like them, Bailey was not much interested in catching and prosecuting them—not this time. It was clear that lawmen had already busted hundreds of stills in the area, and this wasn't the outcome he wanted from his investigation. The approach had done little to stem the moonshine tide in the first place. So Bailey turned his attention to prosecuting the masterminds who had made Franklin County's production possible on such a large scale. It didn't take him long to realize that trainloads of sugar, cans, malt, and even corn were coming into the county regularly and that millions of gallons of hooch were going out. Only slowly did he begin gathering evidence about the ringleaders, but when he did he knew he had uncovered a grand liquor scheme that involved even the county's most powerful elected officials. He called on the small-time sellers as informants, and he would eventually use hundreds of them as witnesses before the grand jury, but his targets would be higher up in the pyramid—all the way to the top of the law enforcement community, in fact. Specifically, Bailey had set his sights on Carter Lee, commonwealth attorney, along with the sheriff and his deputies.

It all seems naive now, but for decades antiliquor campaigners believed alcohol would go away if only the government could make it hard enough to make and buy. It was their generation's “just say no” crusade, and for fourteen years the whole nation had been absorbed by its Prohibition's moral power. Relentless preaching by teetotalers, including the National Women's Temperance Union, Prohibition Party, and the Anti-Saloon League, succeeded in convincing enough lawmakers, if only temporarily, that the government could legislate away social problems by simply outlawing the liquid spirits. Preachers and their followers had begun their antiliquor crusades as early as the 1840s, and by the 1900s states were beginning to do their part to stop sales. The crusaders fought saloons and public beer halls, believing that if they could close legal watering troughs they could help rest...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- 1 - Conspiracy Trial in the Moonshine Capital of the World

- 2 - Wettest Section in the U.S.A.

- 3 - Appalachian Spring

- 4 - Elder Goode

- 5 - Last Old Dollar is Gone

- 6 - Entrepreneurial Spirits

- 7 - Her Moonshine Neighbor as Herself

- 8 - Murder Trial in Franklin County

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index

- About the Authors