![]()

Ingredient 1

First, start a buzz

How nothing happens without conversation

Conversation as revolution

Britain’s boom commodity of the 1780s was human beings. Tens of thousands of African men, women and children were kidnapped and transported across the Atlantic each year in crowded, filthy slave ships. Those who survived were put to work on Caribbean plantations that produced the second boom commodity of the era, slave-grown sugar.

The elites of the British society – aristocrats, parliamentarians, merchants – made their fortunes from this trade as shareholders in shipping companies or as owners of plantations. Meanwhile, it was an article of faith in British society that the slave trade and slave-grown sugar were cornerstones of national prosperity. In 1773 the value of British imports from the island of Jamaica alone was five times that of the thirteen American colonies put together.

“If, in 1787, you had stood on a London street corner and insisted that slavery was morally wrong and should be stopped, nine out of ten listeners would have laughed you off as a crackpot,” wrote historian Adam Hochschild in Bury the Chains, his gripping account of the British anti-slavery campaign.1

Yet Britain was soon to be engulfed in one of the great social change campaigns in history. Within a year, abolition committees had sprung up in every major city and town. Parliament received more petitions against slavery than on every other issue combined. Anti-slavery tracts packed book-shop shelves. Anti-slavery debates filled newspaper columns and the agendas of debating societies. More than 300,000 Britons were refusing to eat slave-grown sugar. Young barrister Samuel Romilly wrote to a friend about a dinner party he attended in 1789 “The abolition of the slave trade was the subject of conversation, as it is indeed of almost all conversations”.2

The anti-slavery campaign, however, faced a powerful, well-financed, exceptionally well-connected industry fighting for its survival. The House of Lords was dominated by pro-slavers and sugar lobbyists who formed a seemingly immovable obstacle to change. The abolitionists came achingly close to achieving their goals in the next few years, but then suffered a tremendous setback. The Napoleonic Wars commenced and conservatives used the war hysteria to taint abolitionists as pro-French. Soon, leading anti-slavery activists were in jail and the rest went underground or withdrew from public life.

It appeared the slavers had won. But then history turned again. Nelson’s victory over the French at Trafalgar transformed public hysteria into elation and an extraordinary thing happened. The anti-slavery crusade reignited with such ferocity that it was as if the decade of suppression had never occurred. Finally, in 1807 a bill banning the slave trade passed both houses of Parliament. Within a few years, the same Royal Navy that had been protecting the slave ships was hunting them down in the waters of the Atlantic.

What caused this extraordinary social revolution? Quakers, a tiny, often persecuted, religious minority on the margins of British society had campaigned passionately against slavery for decades. But as outsiders their voices counted for little. In the great campaign that arose after 1788 the Quakers would be the hard-working footsoldiers, but abolition did not gain traction until a fortuitous chain of human interactions occurred.

The change seemed to begin in 1783 when news of an atrocity began to circulate in anti-slavery circles. The captain of the slave ship, The Zong, had cast into the sea 133 slaves who were too ill to be sold. He fraudulently attempted to recoup the loss through an insurance claim. The insurance company disputed the claim and the matter ended up in court. The story received little attention in the press, but Quakers rapidly spread the news through a letter-writing campaign.

The story eventually reached a prominent Anglican clergyman, Dr Peter Peckard, and it so disturbed him that he preached a sermon condemning the slave trade as a “most barbarous and cruel traffick”.3 Not long afterwards, he was appointed Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University and in 1785 he set as the topic of Cambridge’s prestigious Latin essay contest the question Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare? Is it lawful to makes slaves of others against their will? A 25-year-old divinity student named Thomas Clarkson entered the contest. He knew little about slavery and entered with the sole ambition of winning. Yet as he researched the topic, he became overwhelmed with horror at the barbaric stories he discovered – which included, for instance, the routine burning alive of rebellious slaves on plantations.

He won the Latin essay competition, and, still seething with outrage, marched into the London office of the Quakers who had long campaigned in the wilderness. At last they had an Anglican clergyman – that respectable cornerstone of English society – on their team. It was Clarkson who sought out and recruited William Wilberforce, friend of Prime Minister William Pitt, the powerful and popular orator who would lead the anti-slavery campaign in Parliament. And it was Clarkson who tirelessly crisscrossed Britain, addressing tens of thousands of people in abolitionist groups and public meetings.

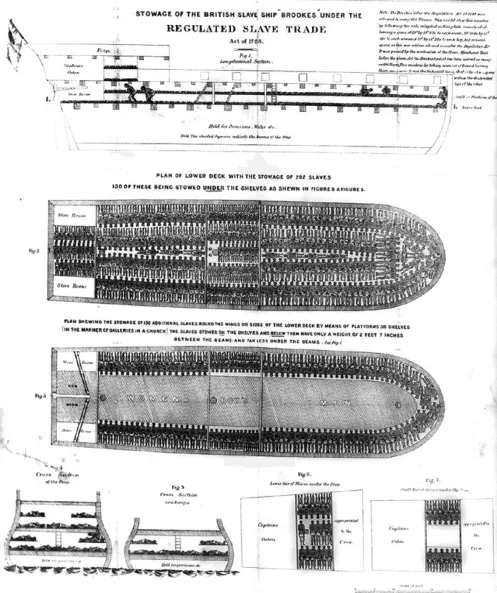

Clarkson took to those meetings not just his moral indignation but real-life stories he had meticulously collected from sailors and slave traders. He took objects people could see and touch: slavers’ implements of torture and mementoes of African life. And he took a dramatic visual prop: the plan of 482 slaves tightly packed in the slave ship Brookes. The plan had fallen into the hands of activists in the port city of Plymouth and was quickly transported to Clarkson and the Quakers who realised its value, reworked it into a poster and distributed thousands of copies. The image soon appeared in newspapers, magazines, books and pamphlets. It “seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it,” and became one of the most influential campaign posters of all time.4

The abolitionists invented the whole armoury of tools modern activists take for granted: the campaign logo, direct mail fundraising, the campaign newsletter, the trade boycott, investigative journalism. However, at the core of their campaign were human interactions. In public meetings, debating societies, coffee houses and at dinner parties people met other like-minded individuals who shared credible stories that sparked outrage and hope.

Hochschild’s account demonstrates how a social and political transformation is really built out of interconnected chains of person-to-person interactions. Stories, outrage and hope pass, like a contagion, from person to person. Highly connected, credible individuals play a vital role in this process. It was not, as the Quakers discovered to their discomfort, enough to be right. Social change is a human phenomenon with its own rules and momentum. The most important of these rules was, clearly, that change must be something people want to talk to each other about.

The power of a confronting image. The abolitionists’ poster of 482 slaves tightly packed in the slave ship Brookes became one of the most influential campaign posters of all time. It “seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it.”

But not all talk is the same. In the anti-slavery debate a pivotal change took place around 1788. Before 1788 slavery was widely known and disapproved of in polite circles. Yet few people believed anything could be done about it. Before 1788 the talk was all about inaction and blame. It was disempowered talk. But then something changed. People began to hear stories about others just like themselves signing petitions – enormous petitions that were a buzz item in their own right. And there were the stories about Englishmen refusing to buy slave-grown sugar. Refusing to buy sugar! Amazing. No one had ever heard of such a thing.

Around 1788, the talk turned from stories about passivity and failure to stories about action. It was like a dam had burst. Suddenly enormous numbers of people in every social class found it possible to imagine themselves actually doing something about slavery. And, when opportunities arrived, they did. They signed petitions, attended meetings, wrote letters and marched until the pressure on Parliament was immense.

The anti-slavery campaign shows how conversations start revolutions. As historian Theodore Zeldin wrote in his book Conversation,

Humans have already changed the world several times by the way they had conversations. There have been conversational revolutions which have been as important as wars or riots or famines. When problems have appeared insoluble, when life has seemed to be meaningless, when governments have been powerless, people have sometimes found a way out by changing the subject of their conversation, or the way they talked, or the persons they talked to.5

Zeldin’s comment arose from his study of intimate conversations in history. The ideas of Voltaire and Rousseau, for instance, circulated for decades in polite intellectual circles, but it was only when ordinary people began to talk about inalienable human rights and the corruption of monarchy that the old Absolutist regimes of Europe tottered and collapsed. A handful of courageous women campaigned for female suffrage for years, but it was only when the subject became a ubiquitous subject for dinner conversation that laws began to be passed. Eastern European intellectuals circulated samizdat literature in secret for decades, but it was only when ordinary people openly criticised the communist gerontocracies that the Iron Curtain states collapsed. Talk, it seems, can make history.

Conversation as problem-solving

Conversation is how communities face up to their challenges. Groups of people are always being challenged by new circumstances. Politicians make new policies. Natural disasters occur. The climate changes. There are new ideas, technologies and threats. Change looms and societies have to figure out what it means and how to respond. A period of fluid, buzzing conversation follows and then opinions set like custard, and people act on the basis of what they have heard others (and themselves) say.

The story of one community facing a natural disaster illustrates the process. In March 2001 a powerful low-pressure system swept over the north coast of New South Wales, bringing torrential rains that flooded rivers, burst levees and caused tremendous stock and crop losses.

In the town of Grafton, all 12,000 residents knew a flood surge was rushing down the Clarence River towards the city. All that stood between that community and disaster was an 8.2-metre flood levee. On Saturday evening, the Bureau of Meteorology issued a warning that the Clarence would rise to 8.1 metres. At that point, the State Emergency Service gave the order to evacuate the town.

The order was issued by radio. It was reinforced by police cars with loudhailers cruising the streets. Alert to the danger and glued to their radios, virtually the whole community heard the evacuation order. Yet to the bewilderment of the authorities the order was systematically disobeyed. Fewer than 13 per cent of flood-prone residents left their homes during the nine hours the order was in effect. As it happened, the flood topped at 7.75 metres, which was just as well because the real height of the levee turned out to be only 7.95 metres. The city came within a handspan of calamity.

What caused this episode of mass disobedience? A few weeks later the authorities asked a social researcher to find out.6 He discovered that 97 per cent of residents heard and understood the evacuation order. What’s more, they understood the danger they were in. Virtually everyone knew the levee could be overtopped and were keenly following radio announcements.

So why didn’t they obey the direction? The researcher uncovered two significant facts. First, after residents heard the evacuation message, they talked it over with people they knew. They especially sought the views of longer-term residents, many of whom, it transpired, replied that the water “never gets up to here”.

Second, they looked around for evidence to confirm whether an evacuation was really taking place. They saw that despite queues at service stations, and supermarkets selling out of batteries, bread an...