On New Year's Eve 1900, Liang Qichao—thirty years old and already a prominent Chinese scholar and political activist of his time—was aboard a ship sailing across the Pacific to North America. Too excited to sleep, Liang stayed up that night and composed a long, passionate poem to mark the historic moment that he was experiencing: “At the turn of the century / astride the East and West.”1

Reflecting on the rise and fall of various civilizations around the world in the past, Liang hailed the dawn of a new epoch, the Pacific Century. The new era, as Liang saw it, was full of potential and grave danger for his motherland, China, which, as an ailing empire, was struggling for survival and renewal. Eagerly, Liang anticipated his upcoming visit of the United States, “a wondrous republic” as he put it, so that he could “study her learning, inspect her polity, and behold her dazzling brilliance.”2

In his outburst of enthusiasm for the United States of America, Liang Qichao exemplified a keen interest shared by many Chinese at the time. Deeply troubled by a severe national survival crisis that China had experienced ever since the middle of the nineteenth century, these Chinese recognized the urgent need for changes. The Western Powers, armed with modern technology, had repeatedly defeated the once-proud Chinese empire and were poised to carve up the ancient land as their colonies. Anxiously the Chinese looked abroad for secrets of national success and, from early on in their quest, a young republic sitting on the other side of the Pacific Ocean drew their attention. The United States, so extraordinarily different from China, was thriving splendidly. Not surprisingly, therefore, Liang Qichao, a perceptive scholar and an idealistic statesman recently exiled from China for his reformist efforts, had high hopes for his upcoming tour of America.

Fifty years later, the Chinese admiration and enthusiasm for America so typical of Liang and his generation would have all but evaporated, replaced by scorn and hostility. By then, the Chinese Nationalist government led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi), which the U.S. strongly supported, had just lost a war to Communist rebels. The People's Republic of China thus created would soon confront the United States in a war on the Korean peninsula. These larger historical events alone would have been sufficient to turn warm feelings into bitter antagonism. Still, evidence indicates that the seeds of hostility had been sown long before the sharp downturn in Sino-American relations in the late 1940s. During the half-century between Liang Qichao's first visit to the United States and Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong's famous farewell to U.S. Ambassador Leighton Stuart, the Chinese nation had heatedly debated the proper understanding and assessment of the United States—what kind of a country it was, and what lessons China might or might not learn from it. This was far from a leisurely discussion, because the argument had everything to do with what the Chinese people wanted to make of their own country. The Chinese debate on America during this period thus gives us more than a hint of how the Chinese would contemplate the United States in the coming decades.

I

Liang Qichao did not actually reach North America on his 1900 voyage. As it happened, upon arrival in Hawaii, he received news that some of his fellow reformers back in China would stage an uprising against the ruling Qing Dynasty. Two years before this time, in 1898, Liang and some progressive Chinese had pushed a reform movement to modernize China. That earlier endeavor had the backing of the young emperor then, Guangxu, but it was hated by many of the old guard in the government, who were led by the emperor's ultra-conservative aunt, Cixi. The dominant Empress Dowager put up with the idealistic reformers for about three months before she decided to crack down. She put the young emperor under house arrest and executed six of Liang's colleagues. The Hundred-Day Reform ended abruptly. Liang himself managed to flee abroad and that was when he set out for America.

From Hawaii Liang hurried home, only to find out that the new plot against the Empress Dowager was yet another false start. No sooner had he returned to China than the news came that the Qing court had uncovered and thwarted the rebellious conspiracy. Again Liang had to go into exile. It was three years later, in 1903, that Liang finally paid his first visit to the United States. Clearly, the spirited Chinese came to America not only as an inquisitive scholar but also as a politician with a burning desire for fresh ideas and new strategies.

To be sure, Sino-American contacts go back beyond Liang's 1903 trip. The first direct voyage from the United States to China took place in 1784, when a ship from Boston, the Empress of China, sailed to Canton on China's southern coast. For much of the following century, however, the young American republic appeared obscure to the Chinese. It was toward the end of the nineteenth century that the United States started to register more prominently in the national consciousness of China. At this time, the United States gave the impression that the country was more benign and peaceful than most other Western powers—Britain or France, for example, which fought wars with China and forced China to sign humiliating treaties. True, the U.S. did obtain the special rights and privileges that the Qing Dynasty had to sign off to the other powers, and the U.S. thus also contributed to China's national-survival crisis. For the most part, however, the United States seemed to be interested in commercial opportunities and did not harbor territorial ambitions in China, a fact for which the beleaguered Chinese were rather thankful. The U.S. did, in 1900, join seven other powers in an allied expedition to China to suppress an antiforeign uprising raging in China then, the Boxer Rebellion. But it was also at this time that Washington put forward the famous Open Door Doctrine, calling upon the foreign powers to respect China's territorial, if not sovereign, integrity. Under this arrangement, China could continue to exist as one country while the Western nations would maintain and expand their privileges in the eastern land. This was far from ideal for the Chinese; but, given their lot at the time, many Chinese were relieved to see that, partly due to the U.S. intervention, their country would avert partition or total colonization, for the time being at least.

China's relatively positive view of the United States also arose from the fact that many Americans were actively involved in charitable causes in China, having established and worked at numerous religious, medical, and educational enterprises. Deeds such as these mitigated the ill effects of American offenses such as the unfair treatment of Chinese immigrants in the United States, which in 1904–05 gave rise to a widespread Chinese boycott of American goods in protest of the U.S. government's discriminative policies.3 Overall, compared to the other haughty Western powers, the United States appeared to be gentle, even benevolent, with a sense of justice as well as compassion for the less fortunate. On both sides of the Pacific, therefore, there was a feeling that a “special relationship” existed between China and the United States, a relationship in which the U.S. was destined to guide and assist China in her march toward modernization.4

To some Chinese, the appeal of the United States came not only from its benign policies toward China but also from America's particular national experience. The Chinese, who at the time were engaged in a difficult struggle for national survival, could not fail to notice that the U.S. had fought successfully for her own independence. Equally fascinating to the Chinese was how swiftly, in just one hundred years or so, a small group of colonies rose to become a great power in the world. Quite naturally, the Chinese wanted to know the secret for America's remarkable success.5

It was against this backdrop that Liang Qichao went on his tour of the United States in 1903. A prodigy from a small town outside Canton, Liang had received solid traditional Confucian training and passed the provincial level of China's onerous Civil Examination at the tender age of sixteen. He rose quickly in academic and political circles, emerging as a prominent leader of the Hundred-Day Reform that took place in 1898. As a man who took pride in constantly waging a war against his past self, Liang the scholar, politician, and popular journalist proved to be an astute observer of the American scene, who was particularly effective in relating his new experience to the situation back in China. After spending six months in North America, Liang published his observations and reflections in a book, Notes on a Tour of the New Continent, which became popular reading for a whole generation of Chinese eager to learn about a fascinating and yet mysterious land.

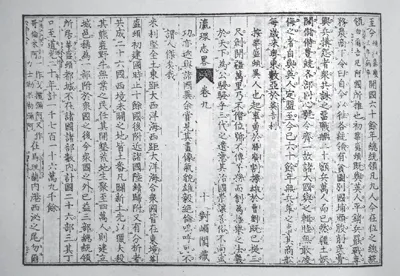

Figure 1.1

Text from A Brief Survey of the Maritime Circuits. Authored in the middle of the nineteenth century by Xu Jiyu, a Confucian scholar-official, the book was one of the earliest Chinese works that provided a reasonably detailed description of the world. Here, Xu tells the story of George Washington: “Washington is an extraordinary man. He was courageous as a rebel and more accomplished in taking control of territories than Cao and Liu [from the era of the Three Kingdoms in Chinese history]. Having conquered with his three-foot long sword and founded a state comprising vast land, he did not usurp the ruling position nor did he pass his power to his descendents. Instead, he created a system based on elections. This spirit approaches the high ideal of ancient Chinese sages—‘The world belongs to all people.’ Furthermore, in government, Washington respected good customs and did not rely on military strength only. This also differed significantly from the ways of other countries.”

Liang traveled extensively in the United States. He toured the New England and Mid-Atlantic states; he went from Chicago on the Great Lakes to New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi; he journeyed across the great prairie, climbed over the Rocky Mountains, and arrived in the Golden State of California. Liang's status as a former statesman gave him wider access to American society than other Chinese in the U.S. at the time, who were mostly confined to a small and strangely mixed world of restaurants, laundries, and ivory towers of higher education. While in America, Liang not only mingled with his fellow-countrymen in Chinatowns but also met luminaries such as John Hay and Theodore Roosevelt.

America left strong impressions on Liang Qichao. At one point in his book, Notes on a Tour of the New Continent, Liang described what an extraordinary experience it was to travel and progress from the backwater countryside of China to the urban centers of America. Coming from interior China and arriving in Shanghai, the Chinese traveler marveled at the splendor of Shanghai and lamented the shabbiness of inland China. Leaving Shanghai behind and reaching Hong Kong, the traveler was struck by the magnificence of Hong Kong and now recognized the mediocrity of Shanghai. In similar fashion, with ever-growing awe, the traveler made his way through Japan and California, and finally arrived in New York—“the ultimate spectacle on the planet.”6

What are the secrets of America's enormous accomplishment? In his search for an answer, Liang made a point of seeking out some prominent Americans for their opinions. In New York, for instance, he went to see J. P. Morgan, whom he described as “the Napoleon of the business world.” The great banker's response to Liang's inquiry on the key to success was simple enough—“solid preparation”—a truism that Liang readily accepted, probably having the untimely death of the Hundred-Day Reform in mind.7

But surely there was more to America's triumph than good planning or effective execution? Upon much reflection, Liang settled on what he termed as “American Spirit.” He discussed the issue with a friend and they agreed that this was what truly mattered. To understand why the American nation had done so well, they suggested, peopled could simply look at the operation or the upkeep of “an American school, an American platoon, an American drugstore, an American factory, an American family, or an American garden.”8 In all these establishments, present was a dynamic spirit of self-reliance and self-motivation. The vigor with which Americans went about their daily business indicated a kind of idealism, which Liang characterized as a mixture of aestheticism, heroism, and religious transcendentalism.9

With an understanding of America such as this, Liang faulted contemporary Chinese for their “lack of high ideals,” which he considered a major flaw. Forget about lofty ideas such as national salvation, Liang said, “we Chinese do not even know how to walk.” When a Westerner moves in the street, “he keeps his body straight and his head upright … and his steps are brisk, as if he is always on some important mission.” In contrast, when a Chinese gets on the road, “his body bends, coils, twists, as if it cannot bear any weight at all”—“it is so maddening to see how the man saunters ever so slowly.”10 The lack of an enterprising spirit, Liang believed, was a major cause of stagnation and decay in China.

Admiring as he was of America, Liang did have his reservations. American politics, for instance, were far too plebeian and boisterous for Liang's taste. To this Confucian gentleman, the American political scene “resembles a rowdy market,” where everybody tries to sell his wares—himself—for a good price.11 Government officials in the United States, Liang thought, put too much effort into pleasing the electorate—to the point where they would sacrifice the long-term well-being of the people. So whereas bureaucrats in an autocracy serve their masters slavishly, politicians in a democracy kiss up to the public—“while differences do exist between these two situations, neither is ideal.”12

Liang rationalized his reservations concerning American politics with what he had recently learned about scandals such as that surrounding Tammany Hall, which led him to conclude that politics in major American cities was the “dirtiest.”13 On the national level, Liang thought that the U.S. president's authority was overly circumscribed. In his view, this prevented the chief executive from accomplishing much. Partly due to this, “most U.S. presidents turned out to be of the average sort,” with only five exceptions—Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Grant, and McKinley. The rest were just forgettable. “Only a few decades have passed since their times, but nowadays who in the world remembers Polk or Pierce?”14

It was not that Liang did not know about traditional American distrust of big government. He was aware that Americans valued autonomy and self-government; indeed, he spoke highly of the federal system of the United States. The success of the American republic, he stated, “does not arise from the union itself but from the states that form the whole, and, within a state, not from the state itself but from the municipalities and other localities that make up the state.”15 “Those who fail to understand this point have no right to discuss American politics.”16

Here Liang seemed to be contradicting himself—he applauded the local and regional autonomy in the U.S. system, but he also felt that the central government did not possess enough power. This ambivalence reflects the distinction between Liang the scholar and Liang the politician, as well as the distinction between his understanding of America and his knowledge of China. Liang the scholar could well understand the rationale behind the American system, but Liang the politician could not see much hope that the American idea would work in China under contemporary conditions. At this time, Liang was still a constitutional monarchist rather than a republican; he remained loyal to Emperor Guangxu in Beijing, who was kept under house arrest by the dominant and reactionary Empress Dowager Cixi. Liang still hoped that before long the young emperor would reemerge to lead the reform in China.17

More broadly, Liang's misgivings about U.S. politics resulted from his distaste for what he deemed excessive freedom in American life as a whole. For instance, the ruthless economic competition under the capitalist system saddened him, especially the great disparity betwee...