![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Starting Points

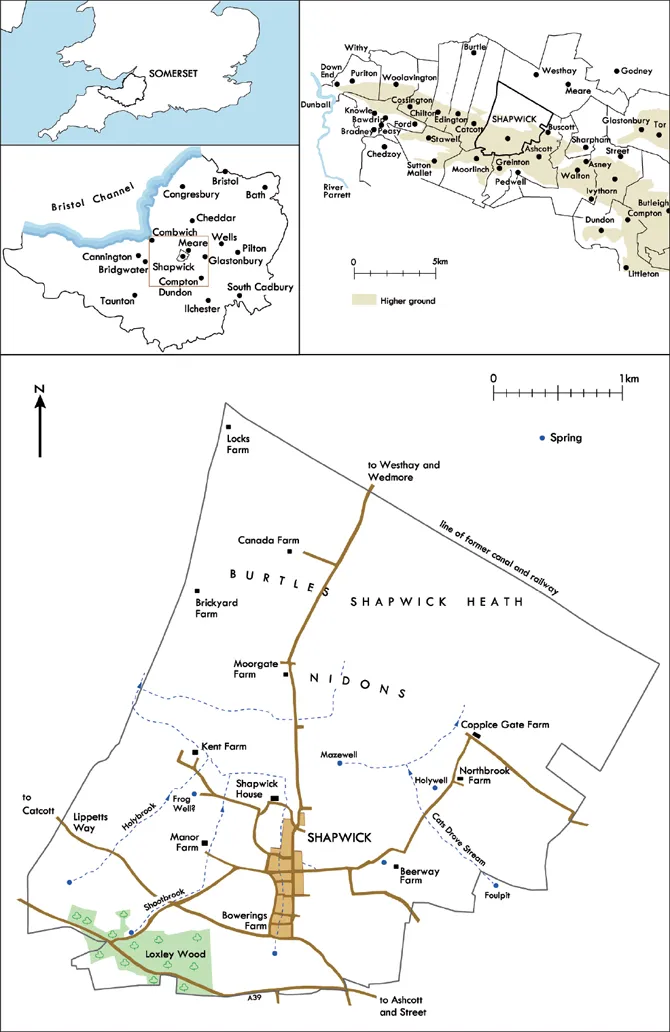

As likely as not you have never been to Shapwick. On the map you will find it marked on the north side of the Polden Hills in the county of Somerset, more or less halfway between the market towns of Glastonbury and Bridgwater (Figure 1.1). Though the village has a church and two grand manor houses, this is not a large place, nor is it obviously picturesque. The low cottages of greyish-white limestone with their red pantile roofs may give the village a traditional ‘feel’, but this belies significant social and economic change over recent decades (Figure 1.2). In common with many rural communities the length and breadth of Britain, Shapwick no longer has a post office, shops, or a primary school. This is essentially a quiet dormitory and retirement village much like any other.

The inquisitive visitor will find evidence for longstanding links with farming at every turn. Not only are there orchards and agricultural buildings, some of them now converted to housing, but the wellordered fields that surround the village are dotted with six working farms (Figure 1.3). With the exception of a mixed woodland at Loxley, much of the upland is given over to pasture for cows and the growing of cereals. Walking downhill, where the Polden ridge flattens onto the Somerset Levels, the floodable land or ‘moors’ was once exploited extensively for peat. Very little is dug there today: the worked-out cuttings lie silent and filled with water. Shapwick Heath, as this northern part of the parish in the Brue valley is known, is now a Nature Reserve of international importance, supporting such rarities as the Large Marsh Grasshopper and Silver Diving Beetles, as well as a diverse ground flora of Sphagnum, sedges, grasses, and wetland herbs between ‘wet woodland’ of willow, birch and alder.1 A little more exploring here might lead the adventurous stranger to one of the several abandoned farms subsiding into the soft peat, or to the ‘sand islands’, named locally as ‘burtles’. Like the Nidons that lie closer to the Polden slope, these are important features of the local topography, but they are hardly the ‘hills’ some older maps extravagantly claim them to be; even the most sensitive of drivers with the least sympathetic of suspensions barely registers their existence.

There is nothing in this picture to suggest that Shapwick is exceptional, at least not in terms of its landscape or its architecture; there is no ruined monastery or castle, for example. Yet, like so many other places in rural England, there are both written records rich in detail and archaeological artefacts buried beneath its gardens and fields that can tell us about the experience of everyday life here and, during the 1990s, this place was chosen as the setting for a wide-ranging historical and archaeological study that aimed to unravel its history and archaeology. This book is the story of that project: a micro-level examination of a well-used English landscape from earliest prehistory to the present day.

Questions and answers

According to recent research, more than half of British people think the countryside is boring and one in ten are hard pressed to recognise a sheep when they see it.2 Yet, for the other half, there is an enduring infatuation with the countryside, so much so that some claim it lies at the very core of our national identity. We cherish its quirkiness, the bold patterning of fields and hedgerows, the creamy stone and bloodred brick of houses, barns and walls. We marry in its country churches, visit its stately homes and navigate its banked lanes. In this ‘forever Ambridge’, villages ‘nestle’, timber-framed buildings are ‘handsome’ and gardens are never less than ‘charming’. The idealised fantasy of our ‘green and pleasant land’ remains potent, a blur of Brooke, Betjeman, Constable, Elgar and Wordsworth that seems, for some at least, largely untroubled by the harsher realities of multi-cultural expectation, fertiliser-sodden soils, rural recession and the depressing decline in numbers of our native birds and flowers.

Figure 1.1. Location map for Shapwick showing selected features of the modern landscape.

Figure 1.2. Shapwick village from the south-west with Mendip beyond.

Figure 1.3. Shapwick village from the air, looking north down the Polden slope towards the Brue valley. Manor Farm is visible to the west of the village with Kent Farm beyond.

It comes as something of a surprise, therefore, to find out just how little we really understand about the development of our rural settlements and their landscapes: the England of village greens and parish churches pictured on jigsaws and the covers of coffeetable books. When did villages like these come into being? Why exactly did this happen? What was there before? How did villages develop once they were established, and what evidence remains now to show us what life was like in the past? Through the intensive study of historical documents, archaeology, botany and topography, these are the fundamental questions we set out to address in this book.

Beginnings

One of the most intriguing puzzles in the English landscape is quite how the rural settlements we see today came into existence in the first place. Until the mid-1960s even the most enlightened of teachers in schools and universities taught their students that the origins of the village lay in the middle of the fifth century AD. According to near-contemporary annals and later texts such as the writings of the Venerable Bede, it was then that a flood of immigrants sailed from southern Scandinavia, Germany and the Netherlands. On arrival, meeting little resistance from the native British population,3 they ‘established’ the English village. This version of events, in which early medieval settlement and its field systems were seen as a ‘package’ imported by ‘German tribes’, had first been proposed by distinguished Victorian historians and, in the second quarter of the twentieth century, their claims were further bolstered by new research from place-name scholars who proposed that settlements could be ordered chronologically through an analysis of their names or toponymy.4 This phasing was backed up by other historical evidence, notably Domesday Book, so often in the past a starting point for economic history, whose contents were thought to provide a moment-in-time snapshot of settlement development around the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066.5

All kinds of assumptions necessarily flowed from this simple proposal. For settlement by invaders to be possible at all, the landscape had, de facto, to be a blank canvas, and so a depopulated and heavily wooded countryside was envisaged in which major programmes of clearance would be needed to create the open spaces necessary for villages and fields.6 The imagined existence of primeval forests, undrained marshes and flooded river valleys was only confirmed by the overwhelmingly natural landscapes described in land conveyances known to us as Anglo-Saxon charters. Then, for so many settlements to be needed there must have been large numbers of incomers. This last point no-one could doubt because of historical narratives that described the arrival of ‘German colonists’ and the subsequent displacement of the native ‘British’ population in a ‘bow wave’ of conquest. This sort of ‘invasion hypothesis’ had long been accepted by prehistorians as a way of explaining change in housing traditions, pottery styles and ways of burying the dead, so why should the historic past be any different? And so, block after block, an academic façade came to be constructed that drew its evidence from several different sources, each reinforcing the validity of the others. The most influential of all landscape history books, William Hoskins’s The Making of the English Landscape, first published in 1955, envisaged a total dislocation of settlement and field system patterns with little or no continuity between Roman and early medieval times.7 ‘The English landscape as we know it today’, wrote Hoskins, ‘is almost entirely the product of the last fifteen hundred years, beginning with the earliest Anglo-Saxon villages in the middle decades of the fifth century’. Even twenty years later, when respected historical geographer Harry Thorpe came to write up his history of the parish of Wormleighton in Warwickshire, he still envisaged Anglo-Saxon settlers living in compact villages with their characteristic ‘-ton’ and ‘-ham’ place-name endings, and ‘-worth’ and ‘-field’ place-names following on later ‘as small groups of venturesome settlers spread north into the dense oak wood making individual hedged clearings’.8 Harry Thorpe was in no way unusual among his peers in imagining a country being resettled anew and thus a kind of purity to Anglo-Saxon economy, society and culture which seemed to bear no mark of what had gone before. Settlements, place-names, regulation and legal customs, open-field cultivation – all these were seen to be Germanic introductions.

Thanks to research since the mid-1960s this version of events has now been entirely overturned. First, place-names were found not to be fixed permanently and, contrary to previous assertions, their names could also be quite unconnected with the foundation of settlement.9 Then, documentary sources, by now being viewed with a more critical eye, showed that William the Conqueror’s great census did not in fact provide a comprehensive ‘yellow pages’ of English villages, as had been assumed, but was in fact largely concerned with those places that owed rent or tax.10 It did not provide an unambiguous list after all. Archaeologists, too, played an important role in dismantling earlier theories by mapping a far higher density of Roman settlement from aerial photography and fieldwalking than had hitherto been suspected.11 This not only showed a more sophisticated network of settlements and communications than had previously been accepted by those who saw Roman influence on the fringes of the Empire as weak and easily swept aside, but also raised uncomfortable questions about how such a large ‘British’ population had really been driven out or exterminated with such extraordinary thoroughness and the extent to which settlements could have been planted afresh if so many suitable sites were already occupied. There was also the realisation that some Anglo-Saxons had arrived long before, as Roman soldiers. At the same time, environmental scientists re-evaluating the pollen record had concluded that the trees had been substantially cleared from the British landscape by late prehistoric times.12 This was a telling point because it effectively decoupled any large-scale changes in vegetation from the post-Roman historical events as described by Bede and others. Earlier claims of ‘the silent and strenuous conversion of the primeval forests of central and southern England’ began to look unduly dramatic.13 Indeed, viewed in this new light, both charter evidence and early legal documents seemed to depict a landscape brimming with people. By the seventh century there were food rents of honey, ale, cattle and much else to be honoured and, as historian Peter Sawyer commented, there was ‘very little room for unworked resources’ in this new vision of the early medieval countryside.14

At the same time, archaeological interest in the Anglo-Saxon landscape itself was also strengthening. Until the mid-1950s the focus in research and excavation had been on cemeteries, grave goods and high-status sites rather than what we might think of as ‘ordinary’ rural settlement. Now, new sites were being identified from pottery scatters and aerial photographs that suggested greater continuity between prehistoric, Roman and Anglo-Saxon landscapes.15 The most exciting results, however, came from large-scale digging at sites such as Catholme (Staffs), Chalton (Hants), Cowdery’s Down (Hants), Mucking (Essex) and West Stow (Suffolk) that discovered the foundations of early medieval structures.16 Once the postholes were plotted out to reveal timber buildings, it was realised that the layouts of these settlements were not at all similar to the kinds of villages seen on modern Ordnance Survey maps: they seemed to be more loosely structured and less planned, and many of them were short-lived too. There was no sign at all of the classic nucleated village plan that earlier generations of historians had so confidently predicted had been founded in the fifth century AD.17 Once more, when archaeologists came to excavate beneath villages that had been deserted in the later Middle Ages, Anglo-Saxon deposits were more elusive than they expected. Later medieval villages, it seemed, were not, after all, the successors to Anglo-Saxon villages – so when exactly had the villages we see today come into being and why?

By the time the Shapwick Project was getting underway in the late 1980s the ‘invasion’ hypothesis was no longer under serious consideration. In its wake were new concepts about how villages might have come into existence. The first was planning: the deliberate creation of larger settlements with ordered layouts to replace an earlier, more dispersed pattern of farmsteads and hamlets.18 A second mechanism of settlement formation envisaged other villages originating at a cluster of road junctions, small greens, manorial centres and churches, and subsequently growing together as their population increased, leading to what was referred to as a ‘composite’ or ‘polyfocal’ village with a very different kind of plan composed of a number of link...