- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The archaeology of the later Middle Ages is a comparatively new field of study in Britain. At a time when archaeoloy generally is experiencing a surge of popularity, our understanding of medieval settlement, artefacts, environment, buildings and landscapes has been revolutionised. Medieval archaeology is now taught widely throughout Europe and has secured a place in higer education's teaching across many disciplines. In this book Gerrard examines the long and rich intellectual heritage of later medieval archaeology in England, Scotland and Wales and summarises its current position. Written in three parts, the author first discusses the origins of antiquarian, Victorian and later studies and explores the pervasive influence of the Romantic Movement and the Gothic Revival. The ideas and achievements of the 1930s are singled out as a springboard for later methodological and conceptual developments. Part II examines the emergence of medieval archaeology as a more coherent academic subject in the post-war years, appraising major projects and explaining the impact of processual archaeology and the rescue movement in the period up to the mid-1980s. Finally the book shows the extent to which the philosophies of preservation and post-processual theoretical advances have begun to make themselves felt. Recent developments in key areas such as finds, settlements and buildings are all considered as well as practice, funding and institutional roles. Medieval Archaeology is a crucial work for students of medieval archaeology to read and will be of interest to archaeologists, historians and all who study or visit the monuments of the Middle Ages.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Medieval Archaeology by Chris Gerrard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

The discovery of ignorance

At my fyrst cominge to inhabit in this Island Anno 1607 I went to Quarr, and inquyred of divors owld men where ye greate church stood. Theyre wase but one, Father Pennie, a verye owld man, coold give me anye satisfaction; he told me he had bene often in ye church whene itt wase standinge, and told me what a goodly church itt wase; and furthor sayd that itt stoode to ye sowthward of all ye ruins, corn then growinge where it stoode. I hired soome men to digge to see whether I myght finde ye foundation butt cowld not.

(from the memoir of Sir John Oglander describing one of

the first excavations of a later medieval monument, at the

Cistercian abbey at Quarr on the Isle of Wight in 1607,

quoted in Long 1888)

the first excavations of a later medieval monument, at the

Cistercian abbey at Quarr on the Isle of Wight in 1607,

quoted in Long 1888)

Go forth again to gaze upon the old Cathedral front, where you have smiled so often at the fantastic ignorance of the old sculptors; examine once more those ugly goblins, and formless monsters…; but do not mock them, for they are signs of the life and liberty of every workman who struck the stone; a freedom of thought, and rank in scale of being, such as no laws, no charters, no charities can secure; but which it must be the first aim of all Europe at this day to regain for her children.

(Ruskin 1851–3)

In former daies the Churches and great houses hereabout did so abound with monuments and things remarqueable that it would have deterred an Antiquarie from undertaking it. But as Pythagoras did guesse at the vastnesse of Hercules’ stature by the length of his foote, so among these Ruines are Remaynes enough left for a man to give a guesse what noble buildings, &c. were made by the Piety, Charity, and Magnanimity of our Forefathers.… These stately ruines breed in generous mindes a kind of pittie; and sette the thoughts a-worke to make out their magnificence as they were when in perfection.

(from J. E. Jackson, 1862, Wiltshire. The Topographical Collections

of John Aubrey F.R.S., AD 1659–70, page 255)

of John Aubrey F.R.S., AD 1659–70, page 255)

How strange it would be to us if we could be landed in fourteenth-century England.

(from William Morris, 1966, The Collected Works of

William Morris, XXIII, page 62)

William Morris, XXIII, page 62)

There is nothing so stimulating to research as the discovery of ignorance.

(from J. B. Ward Perkins, 1940, page 20)

Chapter 1

Inventing the Middle Ages

Antiquarian views (to c.1800)

Early studies of the monuments and artefacts of the Middle Ages have largely been written out of general histories of archaeology, which have tended to focus upon prehistory. Yet the period between the sixteenth century and the turn of the nineteenth saw the development of ideas and perceptions about the medieval past which still impinge on our understanding today. This chapter sets out some of the motives behind antiquarian activities and the contributions of major institutions, societies and intellectual movements are briefly explained. Attitudes to medieval monuments are seen to be influenced strongly by religious and social affairs and employed in their negotiation. The roles of John Leland, William Camden, William Dugdale, John Aubrey,William Stukeley and John Carter are highlighted.The chapter takes as its closing date the growing influence of the Gothic Revival at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The early antiquarians

Even before the Middle Ages had come to an end, there was already an interest in medieval monuments and material culture. The human remains of bishops, kings and saints were exhumed regularly; the sensational ‘discovery’ in 1191 of the body of King Arthur next to that of his wife Guinevere at Glastonbury being only one of the best recorded examples of a staged spectacle of medieval digging (Rahtz 1993: 42–50). Relics could be stolen or change hands at high prices (Geary 1978) and the opening of a coffin established whether a saint’s body was ‘uncorrupted’ and so promoted their cult. If successfully managed, benefactors became less forgetful and pilgrims too appreciated the replenished cache of relics on view (Gransden 1994). Perhaps, in a very loose sense, these exhumations were excavations but they are rather special and specific examples and suggest no substantial interest in gathering new information about the past.

More promising in the context of this book are those studies of the Middle Ages written before the end of the Tudor age. These were of two broad types. General historical narratives included both inventive contributions by Geoffrey of Monmouth and Matthew Paris, and more questioning writing like Polydore Vergil’s Anglica Historia (1534) which covered English history to

1509. Material culture rarely figured strongly in these accounts, though John Rastell, for example, speculated about the authenticity of Arthur’s seal at the shrine of St Edward in Westminster Abbey (McKisack 1971: 95–125). A second type of study were local chronicles containing antiquarian observations, typified by the remarks of Warwickshire chaplain John Rous on fashions of dress and armour in the mid-fifteenth century (Kendrick 1950: 27). A contemporary of Rous, the topographer William Worcestre jotted down details of the churches and monasteries he visited in his diaries (J. H. Harvey 1969). Noting paced and yardage measurements for buildings, he even made a sectional drawing of a door jamb at the church of St Stephen in Bristol, the city where his most detailed survey was undertaken (Kendrick 1950: plate V; Leighton 1933). This taste for architecture and measurement, together with the record he kept of his journeys, were all unusual for their time but writing an historical survey does not seem to have been William’s intention. His interests were clearly wider and included diary descriptions of his contemporary surroundings as well as notes on local legend, folklore and antiquities. His was a medieval world to celebrate.

Not until the middle of the sixteenth century did historical consciousness become more fully sensitised. Between 1536 and 1540 monasteries gave up their possessions to Henry VIII’s commissioners. In the aftermath, fixtures and fittings were especially vulnerable. Statues, altars, sculpture, window glass, vestments, tombs and books were pilfered, damaged and mislaid. In Aubrey’s phrase, ‘the manuscripts flew about like butterflies’ (1847). Damp and deserted buildings collapsed quickly once deprived of their roofing tiles and were demolished and carted away for construction or hardcore. Those buildings which escaped did so either because they were inaccessible or because they could be adapted to another purpose. Many were partially recycled into country residences or rented out for storage and industrial uses. In England and Wales, nearly 850 religious houses ceased to exist (Aston 1993: 141–50).

Nor were these the only changes. Between 1547 and 1553 parish and diocesan records show that the attack on traditional religion left parish churches with only a handful of their images and vestments. Walls were whitewashed and altars removed. Everyday items of liturgy were stripped and sold (Duffy 1992: 478–503). Few were vocal in their protests, and some would profit from the dismemberment, but, within twenty years, familiarity with the day-to-day late medieval worlds of countryside and townscape, secular and religious, had been fractured and disrupted for all. Heaps of monastic masonry lay strewn about as testament to Henry VIII’s efficiency, and it is claimed that out of the loss and shock emerged a new sense of engagement with the past (Levy 1967).

Monasteries, and particularly the fate of the books in their libraries, were of particular concern. The Welsh lawyer John Prise acquired the foundation charters of those houses he visited on Cromwell’s behalf (Ker 1955). John Bale, himself educated as a Carmelite, published catalogues of the medieval books he knew of (e.g. Bale 1557–9) as well as collecting them for himself and drafting a history of his order (Aston 1973). Similarly, his friend John Leland toured the country examining collections and salvaging monastic tomes for the King’s Library (Carley 1985). Leland’s confessed first purpose was conservation, to preserve the best of the authors whose books were now being dispersed (Leland 1546), but the timing and wider purpose of his travels are especially fortunate for today’s student of medieval archaeology. His writing is rich in contemporary detail of the monastic sites he visited (Chandler 1993) and, subsequently, would provide the basis of more complete catalogues of religious houses. But, as he toured the country, Leland visited all manner of sites of different periods and classes. His notebook entries, though they are not always entirely accurate and sometimes rely on uncorroborated local sources, brim with first-hand topographical observation of castles, industries and town walls. Leland’s reference to a deserted medieval settlement at Deerhurst in Gloucestershire, dating to the 1540s, is probably the earliest to a monument of that kind (Aston 1989).

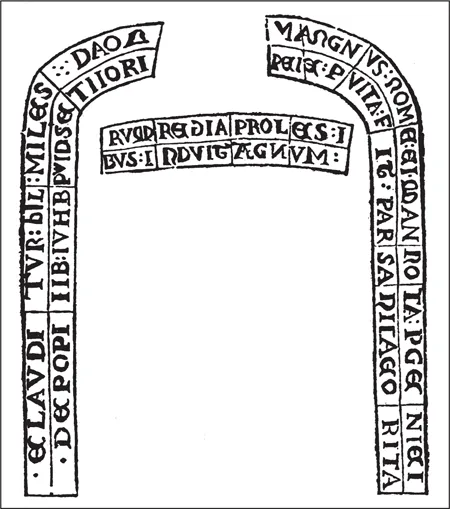

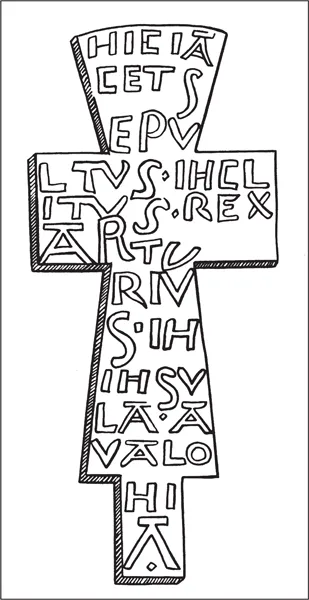

William Camden was not the first to use the term ‘Middle Ages’, but the single illustration in the first edition of Britannia, his pocketbook bestseller of 1586, shows a medieval monument, the Saxo-Norman chancel arch in the church of St John’s-under-the-castle at Lewes in Sussex (Kendrick 1950: 151; Figure 1.1). This was the first published illustration in British archaeology. Later revisions featured one of the first published drawings of a medieval object, the ‘falsified’ lead mortuary cross from the twelfth-century diggings by monks at Glastonbury Abbey (Rodwell 1989: 19; Figure 1.2), as well as county maps and ground plans of medieval buildings.

Whether Camden and his contemporaries would have recognised all this as a growing interest in the artefacts and monuments of the later medieval period is highly doubtful. Mostly, antiquarians had no wish to endorse the Catholic culture and religion of the later medieval period and, indeed, rejected it in favour of more intimate links with a pre-Norman Saxon heritage. When Lawrence Nowell, Dean of Lichfield, began to collect all of Leland’s contributions on the study of Old English place names into a single volume and set about transcribing countless medieval manuscripts, he did so out of sympathy with the views of Archbishop Matthew Parker and his antiquarian colleagues with the church of Saxon England (Flower 1935). When the first county history was published for Kent by lawyer and historian William Lambarde in 1576, the author was careful to strike a balance between horror and applause at the havoc of ‘places tumbled headlong to ruine & decay’ (Lambarde 1576). While it is true that Nowell, Lambarde and John Stow, whose own Survey of London was published in 1598, all indulged a strong sense of local and national pride from which later medieval mouments were not excluded, post-Conquest history was not to be endorsed lightly. Religion often provided the framework for writing and attitudes to the medieval past should be seen as part of this contested arena.

Figure 1.1 William Camden’s recording of the medieval inscription over the chancel arch at the church of St John’s-under-the-castle in Lewes (Sussex), for his Britannia (1586). The first antiquarian book illustration.The arch was incorporated into a new church on a nearby site in 1839.

Even though later medieval archaeology was largely incidental to the purpose of these later sixteenth-century antiquaries, their activities proved influential. In the absence of a Royal Library, Bale, William Cecil, Robert Cotton and Parker all favoured the accumulation of documents in vast private libraries of their own making (McKisack 1971). Contemporary scholars frequently acknowledged their indebtedness to these sources, as Camden and Speed acknowledged Cotton’s library, and these same manuscripts later came to form the core of national collections. The later sixteenth century also set the formula for future antiquarian studies. The contents list for Lambarde’s Kentish Perambulation, for example, opened with a general topographical description before providing lists of hundreds, religious houses and gentry. His text drew upon Bede, chronicles, Domesday Book and royal charters as well as general histories. There was even a coloured location map and he relates the history of many buildings though he did not describe them. Camden’s interests, on the other hand, were certainly more orientated towards material culture and he speculated that ‘monuments, old glasse-windows and ancient Arras’ might provide a novel and independent line of historical inquiry (Camden 1607). Modern archaeological study does find an echo here but we must be careful not to claim too much. Camden may have published later medieval archaeology and architecture but it is only with the benefit of more recent scholarship that the items he presented can be seen as Norman or later in date.

Figure 1.2 The lead cross from Glastonbury illustrated in the sixth edition of William Camden’s Britannia in 1695.When translated from the Latin, the inscription reads ‘Here lies buried the famous King Arthur in the island of Avalon’.The object itself is now lost, but the lettering cannot be fifth or sixth century. This may be a twelfth-century forgery by Benedictine monks eager to establish an Arthurian cult at the abbey and was possibly ‘found’ during the staged exhumation of Arthur and Guinevere in 1191.

This antiquarian movement cannot be divorced from a growing interest in cartography. After the institutional and physical disruptions of the mid- sixteenth century, there was now growing awareness of national and local geography in Britain. Saxton’s county maps were in hand by 1574 and his atlas of county maps was in print by 1600 (Greenslade 1997). Surveying and map-making were becoming priorities for landowners, who were perceiving the landscape in new ways and saw maps as an aid to the improvement of their estates (Johnson 1996). Some of these estate maps already indicated abandoned medieval monuments, but they captured the surveyor’s attention only as landmarks. Moats, windmills, deer parks and strip patterns in open fields were often depicted; the deserted medieval settlements at Fallowfield (Northumberland) and East Layton (Durham) were recorded in c.1583 and 1608 respectively (Beresford 1966; 1967a). By the end of the century map-making was already a semi-professional business and would underpin future generations of antiquarian research.

Excavations and histories of the seventeenth century

For most classically-educated antiquaries, the ‘middle ages’ were just that, wedged in the middle between classical antiquity and the Renaissance. In this growing Enlightenment view the Romans had been Britain’s last link with the civilised world (Trigger 1989). Those who undertook the ‘Grand Tour’ through France, Germany, Italy and the Low Countries only returned more confirmed of this view and identified with the idea of social, cultural and technological progress. And while medieval life was considered barbaric and restrictive there was little inclination to study its monuments. John Evelyn, amongst others, damned without reservation all the greatest monuments of the Middle Ages criticising:

[the] universal and unreasonable Thickness of the Walls, Clumsy Buttresses, Towers, sharp pointed Arches, Doors, and other Apertures, without Proportion.

(Evelyn 1706)

Attitudes to medieval monuments, particularly ecclesiastical architecture, continued to be influenced by the flux in Protestant and Catholic allegiances. An open preference for Gothic architecture, however, did not necessarily signal pro-Roman Catholic affiliation, this assumes too much. For one thing, the Crown’s religious policies were unevenly applied, for another, behaviour and attitudes, inward and outward, were not clearly trammelled. The connection between monuments and religious belief was not so directly made. Having Protestant beliefs did not mean that medieval parish churches and cathedrals should be left in disrepair, far from it, much was done under Elizabeth, James I and later under Archbishop William Laud, to restore the fabric of ecclesiastical monuments as part and parcel of changes to regulations on preaching and services (Oldridge 1998: 37–64). To add to the confusion, understanding of architectural chronology could still be muddled. The Gothic architectural flavours of the new library at St John’s College and the chapel at Peterhouse in Cambridge, both early seventeenth century in date, were intended to link an ‘authentic’, ‘national’ architecture with the pre-Catholic Anglican church (Howarth 1997: 15).

Seen in this context, antiquarians like John Weever, referring to monasteries, felt able to express feelings of loss, even shame, at the ‘shipwracke of such religious structures’ (1631). A mi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: The discovery of ignorance

- Part 2: Into the light

- Part 3: Winds of change

- Bibliography