- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Participatory Action Research

About this book

Participatory Action Research (PAR) introduces a method that is ideal for researchers who are committed to co-developing research programs with people rather than for people. The book provides a history of this technique, its various strands, and the underlying tenets that guide most projects. It then draws on two PAR projects that highlight three integral dimensions: the meaning of participation; the way action manifests itself; and the strategies for gathering, analyzing, and disseminating information.

Author Alice McIntyre describes the various ways in which PAR is carried out depending on, for example, the issue under investigation, the site of the project, the project participants, people?s access to resources, and other related issues.

Intended Audience: This resource is an ideal supplement for graduate courses PAR, qualitative research, and various types of action-based research.

Author Alice McIntyre describes the various ways in which PAR is carried out depending on, for example, the issue under investigation, the site of the project, the project participants, people?s access to resources, and other related issues.

Intended Audience: This resource is an ideal supplement for graduate courses PAR, qualitative research, and various types of action-based research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH

Practitioners of PAR engage in a variety of research projects, in a variety of contexts, using a wide range of research practices that are related to an equally wide range of political ideologies. Yet there are underlying tenets that are specific to the field of PAR and that inform the majority of PAR projects: (a) a collective commitment to investigate an issue or problem, (b) a desire to engage in self- and collective reflection to gain clarity about the issue under investigation, (c) a joint decision to engage in individual and/or collective action that leads to a useful solution that benefits the people involved, and (d) the building of alliances between researchers and participants in the planning, implementation, and dissemination of the research process.

These aims are achieved through a cyclical process of exploration, knowledge construction, and action at different moments throughout the research process. As participants engage in PAR, they simultaneously address integral aspects of the research process—for example, the question of who benefits from a PAR project; what constitutes data; how will decision making be implemented; and how, and to whom, will the information generated within the PAR project be disseminated? As the PAR process evolves, these and other questions are re-problematized in the light of critical reflection and dialogue between and among participating actors. It is by actively engaging in critical dialogue and collective reflection that the participants of PAR recognize that they have a stake in the overall project. Thus, PAR becomes a living dialectical process, changing the researcher, the participants, and the situations in which they act (McTaggart, 1997a).

The originators of the principles, methodologies, epistemologies, and characterizations that inform PAR projects are worldwide and span many decades. In the late 1970s and 1980s, for example, Tandon (1981) and Kanhare (1980) initiated PAR projects in India that addressed adult education and women’s development, respectively. In Columbia, Fals-Borda (1985, 1987) and his colleagues engaged in PAR projects aimed at increasing adult literacy. In neighboring Peru, de Wit and Gianotten (1980) participated in a training program for rural farmers. In Chile, Vio Grossi (1982) worked with local communities to address agrarian reform. Swantz (1982) and Mbilinyi (1982) engaged in PAR processes to improve education for peasant women and other residents of Tanzania. In that same country, Mduma (1982) participated in a PAR project with local Tanzanians to develop agricultural technology.

Elsewhere in the world, Einar Thorsrud engaged in a PAR process that restructured work relations within the shipbuilding industry in Europe (Walton & Gaffney, 1989). In Canada, Jackson and McKay (1982) engaged with local people to improve water sanitation practices in Big Trout Lake. Hall (1977) addressed adult education in a variety of contexts in the United States, and in New Mexico, Maguire (1987) participated in a PAR project addressing male-to-female violence. At the Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee, Gaventa and Horton (1981) developed participatory strategies of reflection, action, and social change with various groups of people addressing a host of social and community issues.

Since then, many of the above researchers, as well as their counterparts in different regions of the globe, have increased the visibility of participatory action research. Similarly, they have re-demonstrated the wide range of issues that can be explored and acted upon in PAR, as well as the variety of contexts where PAR can be conducted. Greenwood and González accompanied industrial cooperatives in the Spanish Basque country as they learned research skills to organize and sustain the cooperatives’ goals (Greenwood, Whyte, & Harkavy, 1993). Maglajlic (2004) engaged in PAR with university-based teams to develop strategies for the prevention of HIV/AIDS in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Hong Kong, Siu and Kwok (2004) carried out a PAR project to generate strategies for improving integrated services for children and youth. In South Africa, Marincowitz (2003) engaged in a PAR project aimed at improving primary care for terminally ill patients. In Guatemala, Lykes (1997, 2001) addressed mental health in the context of state-sponsored violence. In the United States, McIntyre (1997) explored the meaning of whiteness with White teachers, and Brydon-Miller (1993) engaged in a PAR project with disabled persons advocating rights for the disabled. Fine and her colleagues (2003) collaborated in a PAR project with women inmates documenting the effects of prison-based college programs on current and postrelease prisoners.

A closer reading of the above projects, as well as a review of many others not listed here, reveals the context-specificity of participatory action research. Owing to that specificity, there is no fixed formula for designing, practicing, and implementing PAR projects. Nor is there one overriding theoretical framework that underpins PAR processes. Rather, there is malleability in how PAR processes are framed and carried out. In part, that is owing to the fact that practitioners of PAR, some of whom are community insiders and others who come from outside the community, draw from a variety of theoretical and ideological perspectives that inform their practice. Some researchers borrow from Marx’s position that local people need to engage in critical reflection about the structural power of dominant classes in order to take action against oppression. Similarly, Gramsci’s participation in class struggles and his belief that economic and self- and collective actualization can alleviate the uneven distribution of power in society have contributed to the belief among practitioners of PAR that people themselves are, and can be, catalysts for change (Hall, 1981).

Critical theory has also contributed to PAR since it suggests that researchers attend to how power in social, political, cultural, and economic contexts informs the ways in which people act in everyday situations (Collins, 1998; Kemmis, 2001). In addition, Bell (2001) argues that race must not be overlooked in research projects since the projects themselves are embedded in the theories and research practices that inform them—theories and practices that are themselves mediated by race.

Another major influence in the field of PAR is the work of the Brazilian adult educator Paulo Freire (1970, 1973, 1985). Freire’s theory of conscientization, his belief in critical reflection as essential for individual and social change, and his commitment to the democratic dialectical unification of theory and practice have contributed significantly to the field of participatory action research. Similarly, Freire’s development of counterhegemonic approaches to knowledge construction within oppressed communities has informed many of the strategies practitioners use in PAR projects.

As important, feminism has been a key contributor to the scholarship of participatory action research. Feminist theories (see, e.g., hooks, 2000; Collins, 1998; Morawski, 1994; Reinharz, 1992; Stewart, 1994; Wilkinson, 1996) have enhanced the field of PAR with perspectives that have evolved out of a refusal to accept theory, research, and ethical perspectives that ignore, devalue, and erase women’s lives, experiences, and contributions to social science research. Beginning in the 1980s, Kanhare (1980), Lykes (1989), Maguire (1987), Mbilinyi (1982), Swantz, (1982), and Wadsworth (1984) demonstrated and articulated how feminist PAR could be implemented across a variety of contexts. They, and other researchers, continue that tradition today by providing clear frameworks about how feminist-infused PAR projects are “[m]aking the invisible visible, bringing the margin to the center, rendering the trivial important, [and] putting the spotlight on women as competent actors” (Reinharz, 1992, p. 248) in the life of the everyday (see, e.g., Brydon-Miller, Maguire, & McIntyre, 2004; Chataway, 1997; Chrisp, 2004; Fine et al., 2003; Greenwood, 2004; Lewis, 2001; Lykes, 2001; Maguire, 2004; McIntyre, 2000, 2004; Wadsworth, 2001).

There is also a cross-fertilization of research traditions that characterize PAR, each having distinct geohistorical roots. Rapid rural appraisal (Mikkelsen 2001), critical action research (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005), community-based participatory research (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003), and participatory community research (Jason, Keys, Suarez-Balcazar, Taylor, & Davis, 2004) are all variants of PAR that traditionally focus on systemic investigations that lead to a reconfiguration of power structures, however those structures are organized in a particular community.

Some practitioners of PAR follow the tradition of action research—a research approach developed by Kurt Lewin in the 1940s that focuses on group dynamics and the belief that as people examine their realities, they will organize themselves to improve their conditions (McTaggart, 1991). The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London and the Work Research Institute in Oslo expanded Lewin’s work exploring the notion of team building as an essential factor in improving organizational behavior and structure (Boog, 2003). In addition, variants of action research like cooperative inquiry (Heron, 1988; Reason & Rowan, 1981) and action science (Argyris & Schön, 1989) have contributed to a better understanding of the relationship between theory building and processes of change within organizations and local communities.

Variants of PAR also exist within educational settings. Action research (Atweh, Kemmis, & Weeks, 1998; Elliott, 1991; Greenwood & Levin, 1998; Hollingsworth, 1997; Noffke & Somekh, 2005; and Zeichner, 2001), teacher research (Burnaford, Fischer, & Hobson, 2001; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993; Mills, 2006; and Kincheloe, 2003), reflective practice-research (Evans, 2002; McDonald, 1992; and Schön, 1983), and community service-learning (Kay, 2003; Wade & Anderson, 1996; and Zeichner & Melnick, 1996) have contributed significantly to the development of more democratic teaching practices that are linked to students’ and teachers’ everyday lives.

To varying degrees, practitioners of the various research approaches listed above have underlying epistemological, methodological, and ideological differences. Similarly, they have different visions of social research, of the scientific method, and of the political and ethical commitments associated with different research approaches (Greenwood, Whyte, & Harkavy, 1993). For example, many action researchers are trained in management and organizational theory, where the emphasis is on individual and interpersonal levels of action and analysis (Brown & Tandon, 1983). On the other hand, many practitioners of community-based PAR are trained in community development, sociology, education, and political science, where the focus is on communities and social structures (Khanlou & Peter, 2005). The latter approach includes an emphasis on equity, oppression, and access to resources for research participants—factors that are not always present in other forms of action-based research.

Although it is important to highlight the particularities that exist between and among participatory, action-based research approaches, it is unwise to overemphasize their similarities and differences. As Brown (1982) suggests, “Similarities provide a foundation for communication and trust; differences offer possibilities for mutual learning and development” (p. 206). When explored, addressed, and critiqued, both the similarities and differences, as well as the gray areas in between, benefit the field of PAR, assisting practitioners in developing authentic and effective strategies for collaborating with people in improving their lives, effecting social change, and reconstituting the meaning and value of knowledge.

In this book, I use the term PAR to describe an approach to exploring the processes by which participants engage in collaborative, action-based projects that reflect their knowledge and mobilize their desires (Vio Grossi, 1980). I base my approach on the combined beliefs of Paulo Freire and feminist practitioners of PAR—an approach characterized by the active participation of researchers and participants in the coconstruction of knowledge; the promotion of self- and critical awareness that leads to individual, collective, and/or social change; and an emphasis on a colearning process where researchers and participants plan, implement, and establish a process for disseminating information gathered in the research project.

PAR: A BRAIDED PROCESS OF EXPLORATION, REFLECTION, AND ACTION

In addition to the traditions and ideologies that frame and contextualize a PAR project, each project is tailored to the desires of the research participants. Out of those desires, participants decide to act on particular topics that are generated in the PAR process. Participant-generated actions can range from changing public policy, to making recommendations to government agencies, to making informal changes in the community that benefit the people living there, to organizing a local event, to simply increasing awareness about an issue native to a particular locale. Ultimately, the actions that participants decide to take regarding their current circumstances are the result of the questions they pose, examine, and address within the overall research process.

The two projects discussed in this book were framed by initial questions that moved us along in various directions. Those directions provided opportunities for us to develop new ways of thinking about the issues raised in the group sessions. In addition, each new direction resulted in new ideas for how to address specific issues that warranted the participants’ attention.

The initial questions that framed the projects led to other questions that emerged as the research processes evolved. Those questions then became points of entry into further reflection and dialogue that again led to new and different ways of perceiving the issues that were generated in both groups. Sometimes, the insight gained from reflection and dialogue prompted the participants to develop a plan of action. Other times, the participants reflected on a certain issue, discussed various perspectives about it, and ultimately decided that the item under discussion was not worth their time or attention.

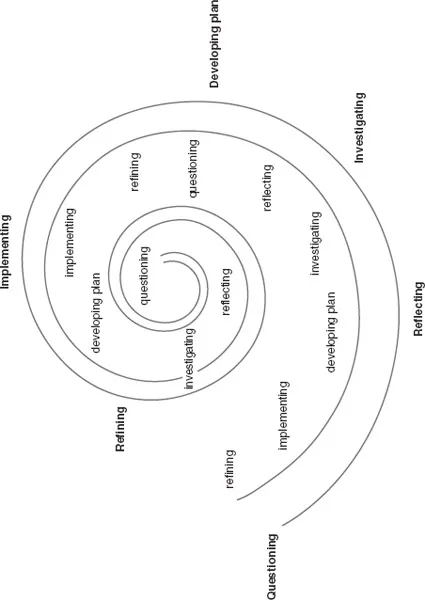

This process of questioning, reflecting, dialoguing, and decision making resists linearity. Instead, PAR is a recursive process that involves a spiral of adaptable steps that include the following:

- Questioning a particular issue

- Reflecting upon and investigating the issue

- Developing an action plan

- Implementing and refining said plan

Figure 1.1 represents how various aspects of the PAR process are fluidly braided within one another in a spiral of reflection, investigation, and action. In the projects described herein, these steps were also linked to a set of activities (e.g., painting, sculpting, storytelling, collage-making, and photography) in which each group of participants engaged. Those activities, in turn, became entry points into yet more questions, more opportunities for reflecting and investigating issues, and more ideas about how to implement action plans that benefited those involved.

In the following chapters, I illustrate how the young people in Bridgeport and the women in Belfast engaged in the recursive process of participatory action research. Their experiences reveal the richness, complexity, and divergent perspectives that existed among them all. Similarly, their experiences demonstrate how participating in processes of critical scrutiny can result in thoughtful actions that reflect participants’ interests and goals.

Figure 1.1The Recursive Process of PAR

ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS AND LOCAL PARTICIPANTS WITHIN PAR

A recurring question in PAR is whether a researcher needs to be requested as a resource by a community or group, or whether a researcher can approach a particular group inviting them to explore a particular issue (McIntyre, 2000). In many cases, the latter experience is the norm, particularly when the researcher is a college/university student or faculty member.

In both the Bridgeport and Belfast projects, I entered the sites as both a practitioner of PAR and an academic—a situation that raises a set of challenges that differ from those generated in PAR projects facilitated by persons unrelated to the academy. As I write elsewhere, there are distinctive challenges that emerge out of and through actual PAR experiences when they are linked to institutions of higher education (McIntyre, 1997; 2000). How academics who are also practitioners of PAR engage those challenges is dependent on the type of institution where they work, the positions they hold, and the multiple identities they carry. It is my experience that academics who engage in PAR need to make decisions about how they negotiate their respective roles in the academy and in the communities where they engage in PAR with caution and common sense. It also helps to hold the belief that, in their own ways, in their own time, and in the contexts in which they live and work, academic practitioners of PAR can shift the perception of the academy as an exclusive space for thinking and theorizing, to a site for collaborative experiences with local, national, and global communities.

Learning to Listen and Listening to Learn

An integral factor in how I negotiate my role as an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Participatory Action Research

- 2. Participation: What It Means and How It Works

- 3. Action and Change in Participatory Action Research

- 4. What Constitutes “Research” in Participatory Action Research?

- 5. Concluding Reflections

- References

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Participatory Action Research by Alice McIntyre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.