eBook - ePub

Social Marketing to Protect the Environment

What Works

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Marketing to Protect the Environment

What Works

About this book

Behavior change is central to the pursuit of sustainability. This book details how to use community-based social marketing to motivate environmental protection behaviors as diverse as water and energy efficiency, alternative transportation, and watershed protection. With case studies of innovative programs from around the world, including the United States, Canada Australia, Spain, and Jordan, the authors present a clear process for motivating social change for both residential and commercial audiences. The case studies plainly illustrate realistic conservation applications for both work and home and show how community-based social marketing can be harnessed to foster more sustainable communities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Marketing to Protect the Environment by Doug McKenzie-Mohr,Nancy R. Lee,P. Wesley Schultz,Philip Kotler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Marketing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION II

Influencing Behaviors

in the Residential Sector

CHAPTER 2

Reducing Waste

For the purposes of this chapter's discussion, we will consider waste generated by the residential sector as items that people living in private or multiunit dwellings dispose of in their garbage, take to the “dump,” or just litter, whether deliberate or accidental. In some cases, these items could have been recycled, reused, given “a longer life”—even never produced in the first place.

The Problem

The problem with waste is that the production, distribution, sales, and consumption of products use the earth's natural resources—many of which are nonrenewable. And the disposal of these products, even in landfills, can have negative impacts on the environment, including those from methane gases and leachate, a groundwater pollutant.

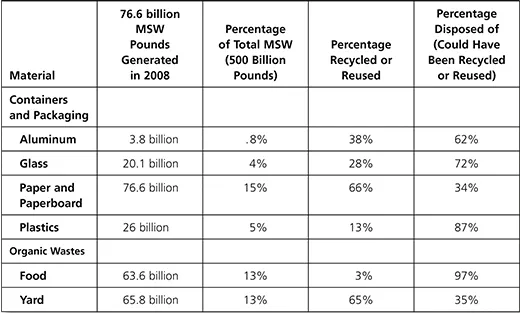

To illustrate the market potential for waste reduction, reports from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provide estimates of the size of the U.S. municipal waste problem, as well as the opportunity. Municipal waste includes residential, commercial, and institutional waste and was estimated to weigh about 500 billion pounds in 2008. (This does not include industrial, hazardous, or construction waste.) As illustrated in Table 2.1, estimates are that as much as 97% of food waste, 87% of plastic containers and packaging, 72% of glass containers, and 62% of aluminum containers that are disposed of could have been recycled or reused. And the potential for this problem is on the rise with—between 1960 and 2008—EPA estimating that the amount of waste each person in the United States created almost doubled from 2.7 to 4.5 pounds per day (U.S. EPA, 2010).

| Table 2.1 | Generation and Recovery of Products in Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) |

Source: Adapted from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2008). Municipal solid waste generation, recycling, and disposal in the United States: Facts and figures for 2008. Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/municipal/index.htm

Potential Behavior Solutions

The top three Rs of the waste management hierarchy are to reduce, reuse, and recycle, providing a rule of thumb guide to relative environmental benefits of waste reduction options. Brief descriptions of each follows, with Table 2.2 then providing a list of related potential behaviors.

Reduce

The best way to reduce our waste stream is to not produce it in the first place. By doing this, we not only decrease the number, size, and environmental impact of landfills but we also decrease use of natural resources, energy, and time that have been used to make and distribute the products. Citizens can be encouraged to reduce consumption most by altering their purchasing behaviors—buying in bulk, buying items with less packaging, paying bills online, giving experiences instead of gifts, and postponing new purchases.

Reuse

Reusing products that have “some life left in them” postpones, even reduces, the use of new resources and the disposal of old ones. As social marketers, we want to develop, promote, incentivize, and/or prompt convenient options to donate or sell unwanted household items such as clothing, furniture, toys, books, magazines, bicycles, cell phones, glasses, garden tools, electronics, and reusable materials from home remodels. We also want to encourage timely maintenance of motor vehicles and appliances to increase their longevity.

Recycle

Recycling is the R that appears to have caught on the best in many countries, making new products out of used ones. Traditional household items that can be recycled include mail, newspaper, glass, aluminum, plastics, and cardboard/corrugated paper. More recently, we are seeing recycling of electronic materials, yard waste, food waste, worn out furniture, clothing, and shoes. Materials for many traditional products are being replaced with ones that have been recycled, including decking from plastic milk jugs and playgrounds from old tennis shoes.

| Table 2.2 | Residential Behaviors to Help Reduce Waste |

| Areas of Focus | Examples of End-State Behaviors That Might Be Chosen for Adoption |

| Reduce |

|

| Reuse |

|

| Recycle |

|

Three success stories for this chapter highlight efforts to influence the residential sector to engage in the three Rs: (1) reducing, (2) reusing, and (3) recycling.

CASE #1 No Junk Mail (Bayside, Australia)

Background

Globally it is estimated that 100 million trees are harvested to produce junk mail each year. In Australia alone, 8.2 billion pieces of “occupant/resident” junk mail are sent out annually, along with an additional 650 million promotional letters. Most of this mail is never even read. Even if recycled, junk mail requires further resources to process and remove inks, dyes, and gloss coatings (Latrobe City Council, 2010).

In 2007, two local residents living in Bayside City, a residential suburb to the southeast of Melbourne on the shore of Port Phillip Bay, formed the Bayside Climate Change Action Group (BCCAG) to advocate for firm government action and to persuade other citizens to adopt environment-friendly behaviors (L. Allinson & C. Forcey, personal communication, 2007). Reducing junk mail was one of their first missions, and five volunteer members designed and implemented an impressive, community-based effort to make it happen.

This case story highlights the group's strategic marketing approach, beginning with collection of baseline data to determine the quantity of junk mail being delivered to each household on an annual basis and concluding with an evaluation after 12 months that indicated a third of households (more than 10,000) adopted the desired behavior—placing a No Junk Mail sticker on their mailbox.

Target Audience(s) and Desired Behaviors

The Bayside community is an area of 37 square km and in the last census (2007) had 35,000 households and a population of 92,801. About 43% of residents are 35 to 64 years old. The campaign focused its research and strategies on household heads they described as being well-intended but not active environmentalists. Those in the active environmentalists’ segment were tapped for advocacy and volunteer efforts.

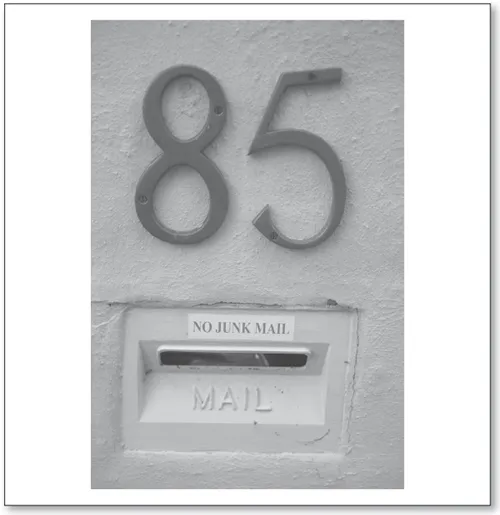

The targeted behavior was a single, simple, and doable one—to adhere a No Junk Mail sticker to the household's mailbox. It was anticipated that this highly visible act would have the intended normative effect.

Barriers and Benefits

The project team brainstormed potential barriers to uptake and then interviewed 20 friends and colleagues to deepen their understanding of their audience. They confirmed the following:

- Some people liked receiving junk mail, using it to identify discounts on offers or for food/recipe or product research.

- There was a concern that the No Junk Mail request would also stop delivery of the two free weekly community newspapers.

- Junk mail delivery was a source of income for local teenagers and retirees.

- Some local small businesses regarded the junk mail medium as a key channel to drive customers and might ignore or push back efforts.

- Not all direct mailers respected the request of a No Junk Mail sticker.

- The sticker itself would need to look professional with a nonoffensive design and made of durable and waterproof materials.

For this “well-intended” target audience, benefits included a chance to save trees, as well as declutter the mailbox.

Description of the Program

The product was the No Junk Mail sticker itself, a small (3” x 1”) sticker that could be attached to the mailbox, usually located at the gatepost. (See Figure 2.1.) More than 200 distribution boxes were developed and filled with the 10,000 stickers and placed by the volunteer team in outlets around Bayside including coffee shops, bakeries, pharmacies, health clinics, sports clubs, schools, play-groups, youth group halls, local libraries, and council offices (place). Boxes were made from discarded energy bar boxes and covered with the No Junk Mail campaign details. Messages highlighted potential tree savings, emphasized the sticker was free, and included instructions to place it on the household letter box (promotion). The cover of the box also listed online sites for catalogs and support, a contact number for refills and questions, and a link to the BCCAG. Children were also tapped for distribution of stickers, providing them at schools to take home and for Boy Scout troops to distribute (place).

| Figure 2.1 | A Sticker Signals to the Postal Staff That the Household Declines Junk Mail |

Source: Lucy Allinson--co-director of the Bayside Climate Change Action Group (BCCAG).

To accommodate the barrier expressed by several individuals who wanted to read some of the junk mail (e.g., flyers with discount coupons), the BCCAG website carried links to mailings that might have been of interest. In addition, several locations including libraries and coffee shops agreed to make copies of these publications available for customers to read and use.

Though the stickers were free (price), messages on distribution boxes suggested that donations would be appreciated and would be used to help fund the printing of additional stickers. In the end, a total of 350 Australian dollars in donations were collected, fully funding the first as well as the second run of 10,000 stickers each. It was also the intention and belief of the group that citizens would feel a sense of pride for their environmentally responsible action.

Campaign promotions deliberately leveraged the strong community involvement and goodwill toward the BCCAG, which had recently received significant media coverage for a pollution prevention sign on a local beach. The “human sign” was a fun way to get the community to make the call for climate action, featuring people gathered together to form the shape of letters, spelling out the message “Halt Climate Change Now.” A picture was then taken from above. Further communications were carried out through a school speakers program and promoted in conjunction with similar BCCAG initiatives. At events related to a solar challenge effort, for example, members were provided stickers and were encouraged to disseminate them to friends and neighbors. At local Al Gore Inconvenient Truth events, stickers were handed out as a symbol of a clear and immediate action that an individual could take. Additionally, a press release to local media generated visibility for the effort, and the BCCAG's website (http://www.baysideclimatechange.com/) provided additional information on the impact of junk mail and where and how to get a sticker.

A pilot with 25 houses on two randomly chosen streets in Bayside provided encouraging results:

- Twenty-four houses were approached and offered a sticker.

- Fifteen accepted stickers.

- Seven refused the stickers.

- Two were undecided.

The campaign ran for an initial period of 12 months from October 2007 through September 2008. Campaign effectiveness was evaluated by volunteers auditing eight randomly selected streets within the Baysi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Section I. Introduction

- Section II. Influencing Behaviors in the Residential Sector

- Section III. Influencing Behaviors in the Commercial Sector

- Section IV. Going Forward

- Appendix

- Index

- About the Authors