![]()

1

A HISTORY OF EVALUATION IN 28½ PAGES

Where we stand

Our brief history of evaluation research begins at the end with an instant observation on the here and now. A metaphor comes to mind. Evaluation is still a young discipline. It has grown massively in recent years. There can be no doubt about it – evaluation is a vast, lumbering, overgrown adolescent. It has the typical problems associated with this age group too. It does not know quite where it is going and it is prone to bouts of despair. But it is the future after all, so it is well worth beginning our evaluation journey by trying to get to the bottom of this obesity and angst.

The enterprise of evaluation is a perfect example of what Kaplan (1964) once called the Taw of the hammer’. Its premise is that if you give a child a hammer then he or she will soon discover the universal truth that everything needs pounding. In a similar manner, it has become axiomatic as we move towards the millennium that everything, but everything, needs evaluating. The nature of surveillance in post-industrial society has changed. The army of evaluators continues to grow. Instead of hands-on-the-shoulder control from the centre, the modern bureaucracy is managed by opening its every activity to ‘review’, ‘appraisal’, ‘audit’, ‘quality assurance’, ‘performance rating’ and indeed ‘evaluation’. These activities can take on a plethora of different forms including ‘self-appraisal’ and ‘peer appraisal’, ‘developmental reviews’, the creation of ‘management information systems’, scrutiny by outside ‘expert consultants’, ‘total quality management’ and indeed formal, social scientific ‘evaluation research’. The monitoring and evaluation process touches us all.

This sense of exponential growth and widening diversity is deepened if one examines change in the academic literature on evaluation. Once upon a time, the evaluation researcher needed only the ‘Bible’ (‘Old Testament’, Campbell and Stanley, 1963; ‘New Testament’, Cook and Campbell, 1979) to look up an appropriate research design and, hey presto, be out into the field. Nowadays, tyro investigators have to burrow their way through ‘Sage’ advice on ‘summative evaluation’, ‘formative evaluation’, ‘cost-free evaluation’, ‘goal-free evaluation’, ‘functional evaluation’, ‘tailored evaluation’, ‘comprehensive evaluation’, ‘theory-driven evaluation’, ‘stakeholder-based evaluation’, ‘naturalistic evaluation’, ‘utilization-focused evaluation’, ‘preordinate evaluation’, ‘responsive evaluation’, and finally ‘meta-evaluation’ before they even get their hands on a social program. Worse still, adopting one of these approaches often means taking sides in the ‘paradigm wars’. Whilst much of the rest of social science has attempted to transcend the positivism versus phenomenology debates (Bryman, 1988), evaluation research is still developing its own fundamentalist sects, which are prone to make declarations of the type: first-, second- and third-wave evaluation is dead . . . long live fourth-generation evaluation (Guba and Lincoln, 1989)!

The sense of bewilderment grows when one considers what it is that evaluators actually seek to evaluate. In the beginning (the 1960s), ‘evaluation research’ referred to the appraisal of the great social programs of the ‘great society’ (the US). In this period, the cost of social welfare soared through the roof (Bell, 1983) and financial, managerial, professional and academic interest groups conspired to follow. Thus what began as ‘social research’ into specific corrections and educational policies soon became an ‘evaluation movement’ which swept through the entire spectrum of social sectors (Shadish et al., 1991). Even when federal funding fell, activity levels were more than compensated for as it became appreciated that one could go down the scale and down the ranks and ‘evaluate’ any function of any functionary. Such a history has repeated itself elsewhere, cumulating with the UK, European, and Australian Evaluation Societies being founded in quick succession in 1994–1995. The ultimate step of ‘having to face up to the process of globalisation’ (Stern, 1995) has been taken with the publication of the first ‘international’ Evaluation journal and a conference in Vancouver billed grandly as the ‘first evaluation summit’.

We can thus say, without too much hyperbole, that ‘evaluation’ has become a mantra of modernity. Ambition is further fuelled by gurus like Scriven who, in describing the scope of what can be evaluated, declares, ‘Everything. One can begin at the beginning of a dictionary and go through to the end, and every noun, common or proper, calls to mind a context in which evaluation would be appropriate’ (1980, p. 4). Here then lies a danger for anyone intent on refining the practice of evaluation (as we are): the term now carries so much baggage that one is in danger of dealing not so much with a methodology as with an incantation.

A corollary of believing oneself to be a jack of all trades is that one often ends up as a master of none. This brings us to the second of our initial observations, to the effect that evaluation research has not exactly lived up to its promise: its stock is not high. The initial expectation was clearly of a great society made greater by dint of research-driven policy making. Since all policies were capable of evaluation, those which failed could be weeded out, and those which worked could be further refined as part of an ongoing, progressive research program. This is a brave scenario which (to put it kindly) has failed to come to pass.

Such a remark is, of course, an evaluation. We have reached ‘e’ in Scriven’s alphabet of nouns and seem to have found ourselves engaged in an instant evaluation of evaluation. We hope to persuade readers of the merits of a rather more scholarly approach to our topic in the course of the book. For now, we rest content with a little burst of punditry by casting our net around some of the recent overviews of the findings on community policing, ‘progressive’ primary teaching and health education (smoking prevention) programs:

The question is, is it [community policing] more than rhetoric? Above I have documented that community policing is proceeding at a halting pace. There are ample examples of failed experiments, and huge American cities where the whole concept has gone awry. On the other hand, there is evidence in many evaluations that a public hungry for attention has a great deal to tell the police and are grateful for the opportunity to do so. (Skogan, 1992)

There are a number of studies that have investigated the relationship between teaching style and pupil progress . . . Most of the severe methodological problems that arose with research on teaching styles, for example surrounding the operationalisation of concepts and the establishment of causal effects . . . have not yet been satisfactorily resolved. This means that we should treat with great caution claims made about the effects of particular teaching strategies on pupils’ progress. (Hammersley and Scarth, 1993)

In recent years, we have seen a number of well-conducted, large-scale trials involving entire communities and enormous effort. These trials have tested the capacity of public health interventions to change various forms of behavior, most often to ward off risks of cardiovascular disease. Although a few have had a degree of success, several have ended in disappointment. Generally the size of effects has been meagre in relation to the effort expended. (Susser, 1995)

A sense of disappointment is etched on all of these quotations. Self-evidently, there is still a problem in distinguishing between program failure and program success in even these stock-in-trade areas of policy making. This state of affairs naturally leads to a sense of impotence when it comes to influencing real decision making, a sense which has come to pervade the writings of even the great and the good in the world of professional evaluation:

We are often disappointed. After all the Sturm und Drang of running an evaluation, and analysing and reporting its results, we do not see much notice taken of it. Things usually seem to go along much as they would have gone if the evaluation had never been done. What is going wrong here? And what can we do about it? (Weiss, 1990, p. 171)

Clearly any body of knowledge which is capable of producing such a cry for help is capable of being ignored and this perhaps is the ultimate ignominy for the evaluator. Perhaps the best example of such disregard that we can bring to mind is the pronouncement of the present UK Home Secretary when he declared, a couple of years back, that ‘Prisons Work’. Now, political slogans uttered in the context of party conferences are normally regarded as no more than part of the rolling rhetoric of ‘crusades against criminals’, ‘crackdowns on crime’ and the like. This pronouncement was particularly hurtful, however, because it deliberately used the ‘w’ word and thus trod directly upon the territory of the evaluation researchers whose raison d’être is to discover whether and to what extent programs work. Mr Howard’s instincts in these matters did not rely on the bedrock of empirical evidence produced by the ranks of criminologists, penologists and evaluators at his disposal. Instead, he figured that armed robbers, muggers, rapists, and so on, safely locked away, cannot therefore be at liberty to pursue their deeds. What we have here then is policy making on the basis of a tautology (and one, moreover, involving rather interesting implications for prison overcrowding). The research is nowhere to be seen. Whilst this is beginning to sound like a cheap jibe at the expense of the politician, it is in fact part of the ‘dismal vision’ (Patton, 1990) that periodically grips the evaluation community. So whilst the view that ‘prisons work’ through incapacitation glides over several decades of hard data on reconviction rates, it is much more difficult to make the case that a policy of incarceration is opposed by secure, consistent and telling evaluations on ‘alternatives to custody’.

So there we have it – the paradoxical predicament of present-day evaluation. On the one hand we have seen an elastic, burgeoning presence stretching its way around the A to Z of human institutions. On the other, we have seen lack-lustre research, a lack of cumulation of results and a lack of a voice in policy making. Picture again our obese, recumbent adolescent. The world lies at his feet (for some reason we cannot help seeing the male of the species). Resources are waiting. Expectations are high. But he is still not quite sure how to get off that couch.

How has this come to pass? A full answer to our own question would have us delve into the organization, professionalization, politics, psychology and sociology of the evaluation movement. In the remaining pages here, we commit ourselves only to a history of evaluation research from the point of view of methodological change. We identify four main perspectives on evaluation, namely the experimental, the pragmatic, the naturalistic and the pluralist. An outline and critique of each is provided in turn, allowing us to end the review with some important pointers to the future. We begin at the beginning in the age of certainty.

Go forth and experiment

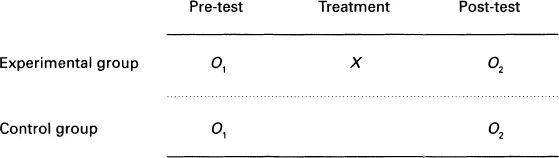

Underlying everything in the early days was the logic of experimentation. Its basic framework is desperately simple and disarmingly familiar to us all. Take two more or less matched groups (if they are really matched through random allocation, you call it real experimentation; quasi-experimentation follows from the impracticality of this in many cases). Treat one group and not the other. Measure both groups before and after the treatment of the one. Compare the changes in the treated and untreated groups, and lo and behold, you have a clear measure of the impact of the program. The practitioner, policy adviser, and social scientist are at one in appreciating the beauty of the design. At one level it has the deepest roots in philosophical discourse on the nature of explanation, as in John Stuart Mill’s A System of Logic (1961); at another it is the hallmark of common sense, ingrained into advertising campaigns telling us that Washo is superior to Sudz. The basic design (untreated control group with pre-test and post-test, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 2) is set down as Figure 1.1 using Campbell’s classic OXO notation (Campbell and Stanley, 1963).

The sheet anchor of the method is thus a theory of causation. Since the experimental and control groups are identical to begin with, the only difference between them is the application of the program and it is, therefore, only the program which can be responsible for the outcomes. On this simple and elegant basis was constructed the whole edifice of experimental and quasi-experimental evaluation. This way of thinking about causality is known in the epistemological literature as a ‘successionist’ or ‘molar’ understanding of causality. The basic idea is that one cannot observe ‘causation’ in the way one observes teaching schemes and changes in reading standards, or burglar alarms and changes in crime rates. Causation between treatment and outcome has to be inferred from the repeated succession of one such event by another. The point of the method, therefore, is to attempt to exclude every conceivable rival causal agent from the experiment so that we are left with one, secure causal link.

At this juncture experimentalists acknowledge a fundamental distinction between their work in the laboratory and in the field. A simple ontological distinction is drawn which regards the social world as inherently ‘complex’, ‘open’, ‘dynamic’ and so forth. This renders the clear-cut ‘program causes outcome’ conclusion much more problematic in the messy world of field experiments. Additional safeguards thus have to be called up to protect the ‘internal validity’ of causal inferences in such situations. For instance, there is the problem of ‘history’, where during the application of the program an unexpected event happens which is not part of the intended treatment but which could be responsible for the outcome. An example might be the comparisons of localities with and without neighbourhood watch schemes, during which police activity suddenly increases in one in response to some local policy directive. The neat experimental comparison is thus broken and needs to be supplemented with additional monitoring and statistical controls in order that we can be sure the scheme rather than the increased patrols is the vital causal agent. Such an example can be thought of as a shorthand for the development of the entire quasi-experimental method. The whole point is to wrestle with the design and analysis of field experimentation to achieve sufficient control to make the basic causal inference secure.

Following these principles of method comes a theory of policy implementation. In Campbell’s case we can properly call this a ‘vision’ of the experimenting society – a standpoint which is best summed up in the famous opening passage from his ‘Reforms as experiments’ (1969):

The United States and other modern nations should be ready for an experimental approach to social reform, an approach in which we try out new programs designed to cure specific social problems, in which we learn whether or not these programs are effective, and in which we retain, imitate, modify or discard them on the basis of their apparent effectiveness on the multiple imperfect criteria available.

What we have here, then, is a clear-cut Popperian (1945) view of the open society, always at the ready to engage in piecemeal social engineering, and to do so on the basis of cold, rational calculations which evaluate bold initiatives.

This then was the unashamedly scientific and rational inspiration brought to bear in the first-wave studies such as the Sesame Street (Bogatz and Ball, 1971) and New Jersey Negative Income Tax experiments (Rossi and Lyall, 1978). These are worthy of a brief description, if only to give an indication of the nature of the initiatives under test. The background to the first was the then radical notion referred to in the States as ‘Head Start’, which we tend to think of more prosaically in the UK as ‘pre-schooling’. The guiding notion, which educationalists are very fond of telling us, is that there is far more cognitive change going on in our little brains between the ages of two and five than at any other interval throughout the life span, and that if we want to reduce social disparity through education, we have to ‘get in there quickly before the rot sets in’. One of the fruits of this notion was the production of a series of educational television programs designed for this age group, which many readers will have doubtless seen and will remember as being very serious about their playful approach to learning. The second example stands as the heavyweight champion, costing $8,000,000 (at 1968 prices) and which itself spawned a variety of replication studies. The core policy under scrutiny was another radical idea, involving scrapping the benefit and social security system and then enlarging the role of the taxation system so that when family income fell below a certain level the ‘tax’ went the other way. The design involved comparing a control group under the standard tax/benefit regime with eight experimental groups which experienced a different balance of ‘guaranteed incomes’. Under test was t...