![]()

Chapter 1

The Collective

The word ‘collective’, jiti in Chinese, can be read literally as ‘grouped individuals’. For many decades, following the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, the collective was developed as a means for people to learn, understand and share their lives. By being extended with a suffix, as ‘collectivism’, it has been valued as a particular energy generated through individuals who have a common goal, a precept of selflessness in favour of collective interests, a communist morality, or a sacred belief in Mao’s world.

In the early development of the new China, mass assemblies became a prominent and familiar phenomenon, and this helped to expand the term far beyond its literal meaning. Sociological and political interpretations of the notion of ‘collectiveness’ in China sometimes refer to this phenomenon as a ‘family’ movement, whereby individuals also belong to their work unit as a focal nucleus of life, or, more precisely in the Chinese term, their danwei, which includes, for instance, factories in the case of workers, schools and universities for students and teachers, hospitals for doctors and nurses, and so on. According to the writer and academic David Bray, danwei is a generic term denoting not only the Chinese socialist workplace, but also the specific range of practices that this embodies. As he defines it:

It is the source of employment and material support for the majority of urban residents; it organizes, regulates, polices, trains, educates, and protects them; it provides them with identity and face; and, within distinct spatial units, it forms integrated communities through which urban residents derive their sense of place and social belonging.1

The danwei functions not only as the state apparatus of political control, but also as a redistributing agency in which rewards and opportunities are linked to individuals’ political attitudes and loyalty.2 In the environment of the danwei, everything is intended to be transparent within the collective, with nothing being personal, in order to ensure faith in communal living. The collective may be designed as a ‘criterion’ of daily life, and constructed as an idealistic identity for ‘the people’ – allowing for no authentic independence, but promoting an overall kind of conformity, within which one can nonetheless, through super-conformity, be recognized and valued with legitimate status.

The Brain

The danwei style of collective was effectively constructed under Mao’s regime. This is to say that, despite the country’s vast population, all the individual collectives that made up the total collective body of China seemingly had one singular brain, that of the Chairman. Every condition and every movement of all the individual bodies was inspired and specifically instructed by the brain. When, on 9 September 1976, Mao died, at the age of 82, the entire country fell into deep mourning. An estimated one million people filed past his flag-draped coffin laid at the Great Hall of the People to pay their final respects. But more than grief, there was a sense of loss and a fear for the uncertainty of the future as China moved forward without its leader. Life would have to carry on, but very differently. Without the critical examination of Mao through artistic reflections, it is impossible to truly understand the collective.

In 1988, Wang Guangyi made his monumental series of paintings, Mao Zedong, representing the Chairman’s ‘standard portraits’ on five large canvases, two of them with red grids and three with black grids.[7] The series was first shown in the 1989 China/Avant-Garde exhibition at the National Art Museum in Beijing, and became one of the most controversial works of the time, marking ‘a turning point in China’s modern art movement’.3 The original intention of this series was to conclude the artist’s ‘liquidation of humanist enthusiasm’. However, after it had been exhibited, Wang suspected that ‘the onlookers, with hundredfold humanist enthusiasm, endowed Mao Zedong with even more humanist connotations’.4 The ‘divine’ images were overlaid with thick grids: practical guides for duplicating and enlarging, and so glorifying, the Chairman. Normally removed once pictures are completed, here the grids remain and overlay a sombre grey Mao, serving as a frame for measurement or analysis. In Wang’s paintings, as critic and curator Karen Smith discusses, the warning barrier ‘required people to pause for a moment before approaching this deity’, and ‘forced an objective reconsideration, literally to put Mao into perspective, a sentiment reinforced by a palette of cold reds and steely blue-greys’.5 The rationale here was simple: by bringing the grid out from beneath the surface of the picture to the forefront, the image was transformed from an object of worship into a subject of judgment.

7 Wang Guangyi, Mao Zedong: Red Grid No. 1, 1988

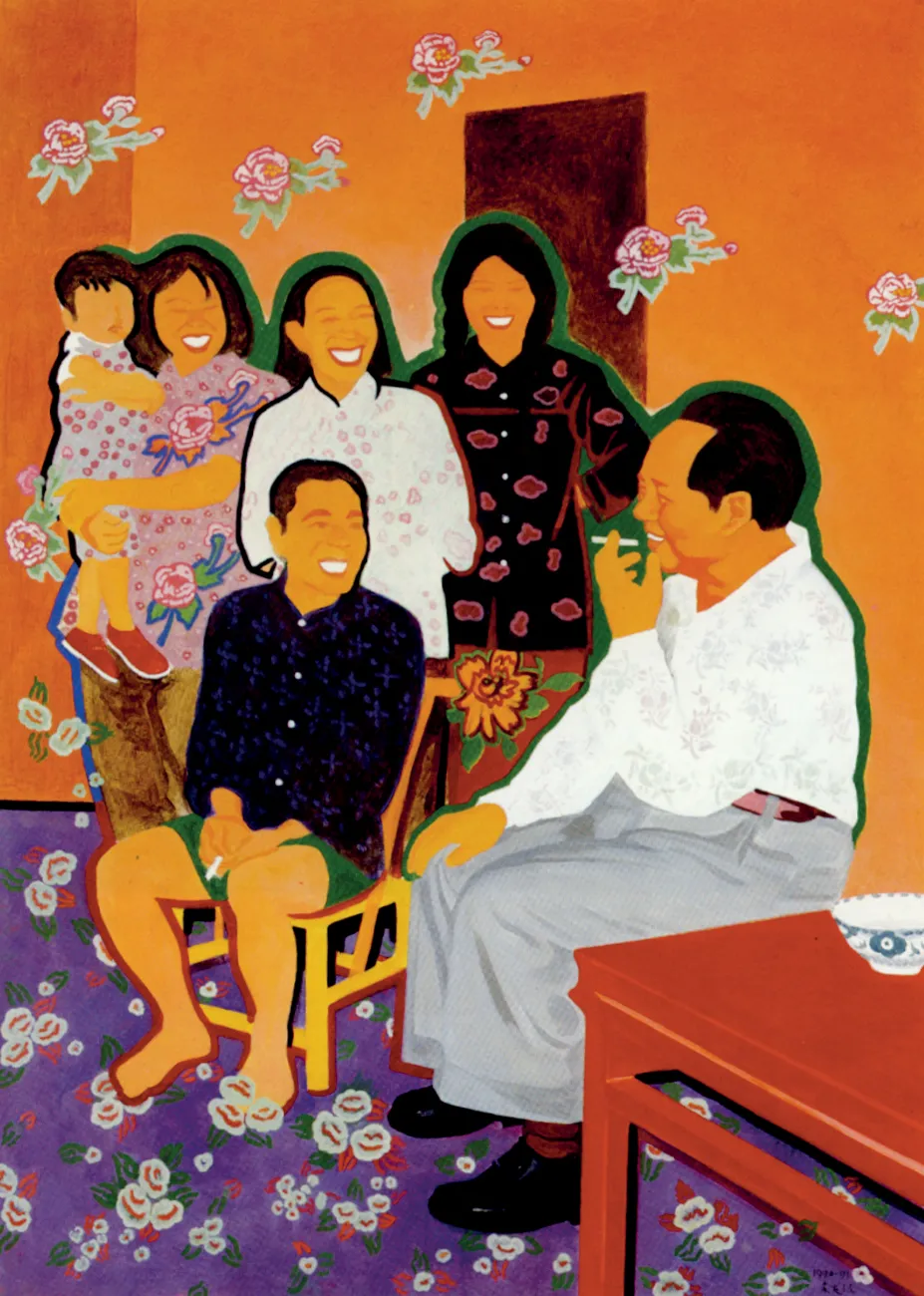

As an artist of a slightly older generation, Yu Youhan experienced the years of the Cultural Revolution while studying in Beijing at the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts. During that time, Yu painted huge images of Mao on a wall of more than 120 square metres (over 1,290 sq. ft) opposite the Tiananmen Tower. To him, the Chairman meant everything – ‘a great leader of the nation, a symbol of China or the East, a book of culture or a particular period of history. Sometimes Mao is avant-garde, but sometimes rather conservative.’6 From the end of the 1980s, however, the artist began to re-portray Mao in a completely different way. Most of his early paintings are based on journalists’ photographs of Mao published in the pictorials officially sanctioned by the state. All the images that were accessible to the public were positive, as well as historically and politically significant, celebrating Mao leading the country and his people on the way to the success of the People’s Republic. In Yu’s series Mao and His People, the leader is positioned in the centre of each work, his pose appropriated from the well-known photograph of Mao at the talks in Yan’an (see p. 7).[8] Instead of the original patched trousers, however, his suit is patterned with flowers, and these are also dotted around the painting, which is turned into a fabric-like composition. Similarly, floating flowers are applied to the 1991 work Talking with Hunan Peasants, based on a 1950s photograph depicting Mao sitting graciously with a family of cheerfully admiring peasants – the men notably sitting, while the women stand – in his home town, Shaoshan, in Hunan Province.[9] The floral patterns were the artist’s own invention, inspired by the paper flowers used as so-called ‘spiritual rewards’ in communist China. Imposed on Mao and the other figures, they appear everywhere in the painting, recalling the native style of folk art. As the artist has reflected, ‘The floating flowers decorate the space quite nicely, and yet make it an unreal and hollow environment. Communism, which we are encouraged to dedicate our lives to, seems to be a beautiful paradise, an unreachable destination. However, people do not have the ability to expose the lie, or break away from the dream.’7 The subjects’ smile, the collective smile, joyfully in unison under the guidance of Mao, represents the over-idealized relationship between the Chairman and his people, while their ignorance of the situation is somehow divulged by their bare white teeth.

8 Yu Youhan, Mao and His People, 1995

9 Yu Youhan, Talking with Hunan Peasants, 1991

Li Shan’s work seems to be even more obviously ‘treasonous’. The painting series Rouge is based on two of the most famous photographs of Mao, one taken during the period of his guerrilla activity in the 1930s and the other comprising a benevolent-looking ‘standard portrait’. The word ‘rouge’ (yanzhi) describes a hue of pink verging on fuchsia, at one time a colour particularly associated with Chinese traditional art, such as Beijing Opera and New Year painting. It is chosen here as the title for its symbolism of something superficial but, at the same time, useful for whitewashing revolutionary ideology and the real prospects of people’s lives.8 In the series, a mysterious lotus-like flower containing the colour rouge is always carried between the lips of the communist leader, who sometimes wears a red-star cap as well as lipstick.[10] On the one hand, this ‘rouge-ization’ of Mao demonstrates the popularization of the Chairman’s portrait and its transformation into a mass icon; on the other hand, the folksy, even vulgar taste for the colour rouge eliminates and insults the sacred meaning of the image of Mao. Art historian Francesca Dal Lago explores further:

An implicit reference is directed toward male homoerotic desire, traditionally associated in China with the theatrical world because of the convention of men playing female roles [in Beijing Opera]. This association – implied both by the use of the colour and by the androgynous, feminized features assumed by the portrait in Li’s series – introduces another recurrent trope of the literary recollections of the Cultural Revolution – that of sexual freedom and liberation experienced during this period. ‘Gendering’ Mao becomes Li’s personal way to vulgarize the figure of the leader and bring this sublime object of desire to a more accessible level. The result of this practice is the projection of the artist’s sexuality onto the icon, the screen of a feminized Mao.9

Although these manipulated versions of Mao were explained by the artist as ‘transferring’ (rather than feminizing) Mao to the state of a purely unisex human being, a visual symbol, or icon of cultural identity, the images – because of Mao’s political and apotheosized status in a patriarcha...