Introduction

Man has always been fascinated by the creatures that surrounded him. Rock paintings and engravings from prehistoric times show that, apart from man himself, it was the large mammalian species that were most often depicted. Among these, the horse played a prominent role in those latitudes where this species was abundant.

After domestication interest in the species naturally deepened as the role changed from simple animals of prey to that of an important economic entity. The horse, unlike almost all other species, was domesticated for its locomotor capacities rather than as a supplier of food or clothing materials. It was this tremendous capacity to move that for millennia gave the horse its pivotal role in transport in many of the major civilizations on this planet and that also made it a most feared weapon in warfare from ancient times until very recently.

As a result of this important role in transportation combined with its proximity to man, the horse became the primary focus when veterinary science developed in the ancient societies and later as it became a flourishing branch of science during the heyday of the Greek and Roman civilizations. It is therefore not surprising that it was during Antiquity that the first scientific comments were made on gait.

The decline of the Antique culture and the subsequent fall of the Roman Empire brought science to a virtual standstill in most of Europe during the dark Middle Ages and it is not until the Renaissance that we see a renewed scientific interest that also extends to veterinary medicine. First directed at the legacy of Antiquity, science took a step forward in the 18th century when the modern approach of making observations and drawing conclusions, later followed by the conjunction of hypotheses with subsequent experimental testing, was adopted. Then we also see the founding of the first veterinary colleges. These focused almost exclusively on the horse, which, throughout this entire period, had maintained its primary role in transport and warfare. It was France that took the lead and it was also French scientists that published the first scientific study completely dedicated to the locomotion of the horse.

France retained the lead in veterinary medicine, and in equine gait analysis, for almost a century until the end of the 19th century. Then, with one notable exception in the United States, German scientists took over and explored with their characteristic thoroughness the possibilities of novel techniques like cine film.

The outbreak of World War II brought this thriving research to a halt. There was no recovery after the end of the war because the mechanical revolution, which had already started during World War I, made horse power redundant and brought to a definitive end the traditional role the horse had played for millennia in transport and warfare. In fact, it looked as if the species would become entirely marginalized.

However, interest in the species was revived at the end of the sixties and in the early seventies of the 20th century when equestrian sports enjoyed an immense popularity that continues to increase today. This popularity has again made the horse into an important economic factor, worthy of serious investment. At the same time, interest in locomotion analysis has revived. This time first in Sweden, but soon followed by other countries and regions where the horse has gained importance as a sports and leisure animal like in North America and North-western Europe. This renewed interest in equine locomotion coincided with the electronic revolution, which made computer-aided analysis a reality, thus creating the possibility for much more advanced and profound studies of equine locomotion than ever before.

The science of equine locomotion is thriving. This book aims to present the state of the art in this branch of science. In the first chapter an attempt is made to give an overview of how this science developed over time against the background of evolving veterinary science, but more so against the background of the evolving relationship of mankind with what has been called our closest ally; the horse.

Prehistoric times

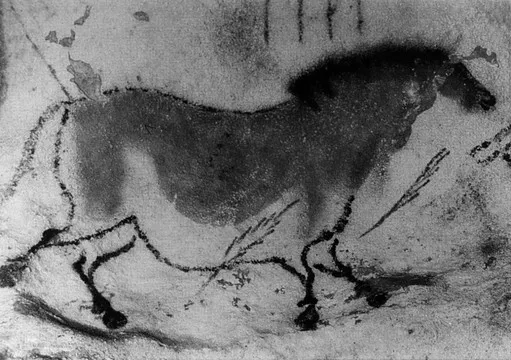

The oldest known art to be produced by man is the rock art found in various caves in the Franco-Cantabrian region, covering what is nowadays South-western France and North-western Spain. Here, about 30 000 years ago the Cro-Magnon race of people began depicting their environment by means of large and impressive paintings on the walls of rock caves. At first still somewhat crude, artistic heights were reached about 15 000 years ago in the Magdalenian period, so called after the rock shelter of La Madeleine, near present-day Montauban. In those days of the last Ice Age, South-western Europe must have known abundant wildlife. In the paintings two classes of animals prevail: ruminants such as cattle, bison, deer and ibex, and horses. The way horses were represented does not reveal a profound knowledge of equine locomotion. In most cases the animals were painted standing with all four legs on the ground, or in an unnatural jump-like action with the forelimbs extended forward and the hind limbs backward, in much the same way as horses were still erroneously depicted in many 18th century and early 19th century paintings (Fig. 1.1). Species like rhinoceros, mammoth, bear and the felidae are present, but to a much lesser extent. Perhaps the plains, which covered that part of Europe in this period, looked much like the great plains of East Africa, such as the Serengeti, nowadays. Here too, ruminants like buffalo and wildebeest are abundant together with equids (zebras), while other species such as rhinoceros and the large cats occur in significantly smaller numbers.

Fig 1.1 Przewalski-type horse as depicted in the cave at Lascaux (about 15 000 BC). Reproduced from Dunlop, R.H., Williams, D.J. (Eds.), 1996. Veterinary Medicine. An illustrated history. Mosby, St. Louis, with permission from Elsevier.

Man was still a hunter-gatherer in those days and, for this reason, the wild animals comprised an essential part of his diet. Remains of large mammals eaten by man, including horses, have been found at many sites. It is interesting to note that the vast majority of rock paintings concerned animals, most of them large mammals, whereas man himself was depicted rarely and other parts of the environment such as the vegetation or topographical peculiarities were never shown. Also non-mammalian species such as birds, reptiles, fish or insects were virtually unrepresented. The rock art found in various parts of Zimbabwe and other parts of Southern Africa was somewhat different. These paintings were made by the Bushmen from 13 000–2000 years ago. Here again, the large mammalian species prevailed, with the zebra representing the equids, but man was depicted more often and there were some paintings of fish and reptiles (Adams & Handiseni, 1991). The Bushmen culture has survived until the present day, though in a much diminished and nowadays heavily endangered form, and it is known that these people, who were hunter-gatherers, lived in a very close relationship with their environment, forming an integral part of the entire ecosystem. It is easy to imagine that under such circumstances the large mammals, which were the most impressive fellow-creatures giving rise to mixed feelings of awe, admiration and a certain form of solidarity, inspired the creation of works of art.

The world changed dramatically when, at the beginning of the Neolithic period about 10 000–12 000 years ago, man changed from being a hunter-gatherer to primitive forms of agriculture and pastoralism. The capacity of most natural savanna habitats to support fixed human nutritional requirements is estimated at only one or two persons per square mile (Dunlop & Williams, 1996). The advent of agriculture and pastoralism meant that the nutritional constraints on population growth were lifted and an unprecedented population growth followed. It also meant that man definitively and irreversibly placed himself apart from his fellow-creatures and outside the existing ecosystems where the numbers of species were determined by the unmanipulated carrying capacity of the environment.

These changes in human society were to a large extent possible thanks to a new phenomenon: the domestication of animal species. It is widely believed that the dog was the first animal to be domesticated about 12 000 years ago. Like most early domestications, this event took place in Western Asia's Fertile Crescent (the area of fertile land from the Mediterranean coast around the Syrian Desert to Iraq), which was the cradle of human civilization. There also the next domestication took place: small ruminants were domesticated approximately 10 000 years ago, sheep and goats in about the same period. Cattle were domesticated 2000 years later in Anatolia (Western Turkey). Cats were domesticated (or adopted man as some people state) as early as 9000 years ago. The first camelids to be domesticated were llamas in South America, perhaps as early as 7500 years a...