- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities

About this book

A step-by-step guide to more synthetic, holistic, and integrated urban design strategies, Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities is a practical manual to accomplish complex community design decisions and create more green, clean, and equitable communities.

The design charrette has become an increasingly popular way to engage the public and stakeholders in public planning, and Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities shows how citizens and officials can use this tool to change the way they make decisions, especially when addressing issues of the sustainable community.

Designed to build consensus and cooperation, a successful charrette produces a design that expresses the values and vision of the community. Patrick Condon outlines the key features of the charrette, an inclusive decision-making process that brings together citizens, designers, public officials, and developers in several days of collaborative workshops.

Drawing on years of experience designing sustainable urban environments and bringing together communities for charrettes, Condon's manual provides step-by-step instructions for making this process work to everyone's benefit. He translates emerging sustainable development concepts and problem-solving theory into concrete principles in order to explain what a charrette is, how to organize one, and how to make it work to produce sustainable urban design results.

The design charrette has become an increasingly popular way to engage the public and stakeholders in public planning, and Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities shows how citizens and officials can use this tool to change the way they make decisions, especially when addressing issues of the sustainable community.

Designed to build consensus and cooperation, a successful charrette produces a design that expresses the values and vision of the community. Patrick Condon outlines the key features of the charrette, an inclusive decision-making process that brings together citizens, designers, public officials, and developers in several days of collaborative workshops.

Drawing on years of experience designing sustainable urban environments and bringing together communities for charrettes, Condon's manual provides step-by-step instructions for making this process work to everyone's benefit. He translates emerging sustainable development concepts and problem-solving theory into concrete principles in order to explain what a charrette is, how to organize one, and how to make it work to produce sustainable urban design results.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities by Patrick M. Condon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Charrette Theory for People in a Hurry

Sustainability: An Imprecise but Useful Concept

The word sustainability brings essential social, ecological, and economic objectives together into one imperative. In the real world, the social, ecological, and economic realms interact with one another in complex and unpredictable ways. The charrette method can accept this multitude of often conflicting objectives without becoming paralyzed by complexity.

Sustainability, as a term, defies precise definition: it is open-ended. Similarly important and powerful terms, such as justice, patriotism, freedom, truth, beauty, God, and faith, also resist clear definition in direct proportion to their power to inspire. The names of concepts that defy simple definition are often the words that most powerfully motivate individuals and cultures.

This is not to say, however, that attempts to define such concepts have not been frequent and wide-ranging. Sustainability is no exception. The most widely accepted definition of sustainability comes from the 1987 report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (also known as the Brundtland Report), which defined “sustainable development” as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. ”1

This elegant formulation conceals a number of complexities. The most fundamental of these reside in an implied limit on planetary resources and in the possibility that the flow of nature’s services could become unbalanced. In short, an ecological view of the physical planet underlies the sustainability paradigm. This view contradicts the still prevailing schools of economic development theory that see the earth and its resources as without absolute limits.

From Watchlike Precision to Messy Complexity

Most credit the work of mid-twentieth-century naturalists and scientists such as Aldo Leopold (1887–1948), Sir Arthur Tansley (1871–1955), and Eugene Odum (1913–2002) for helping to initiate the shift to an ecological worldview. Those who hold to that view focus on the interrelatedness of animate and inanimate systems and on the subtlety of the nutrient exchanges that sustain them. Ecological thinking represented a departure from the still influential mechanistic model of cosmic order. Isaac Newton (1643–1727) and his followers imagined the universe as akin to a great watch, a mechanism of immense precision that responds predictably to causative forces. This assumption still dominates the majority of academic research efforts and underlies the assumptions of most of our planning and design disciplines.

From an ecological perspective, the world is not that simple. The gears in Newton’s cosmic watch never changed shape and size in response to energy and nutrient flows. The watch itself never morphed into a larger, faster, more diverse, more complex machine over time in response to those flows, nor did entire functions disappear to be replaced by apparently unrelated functions. But such transformations are observable everywhere in nature at a level of subtlety and complexity that transcends simple mechanics.

Humans Make It Even More Complex

Brundtland’s definition of sustainability contains a second complication: humans. The ecological worldview, as groundbreaking as it was, seldom seems comfortable including humans inside its framework. Equipped with either a strictly biological or a romantic view of nature, many ecologists have perceived human settlement as an impediment to ecological integrity. Forward-looking thinkers have acknowledged that this view is unnecessary and unproductive. John Lyle, for example, challenges the belief that human activities always require “mitigation” when they affect the natural landscape: “Rather than mitigating impacts, we might create ecologically harmonious development that by its very nature requires no mitigation, recognizing that humans are integrally part of the environment.”2 Green architect and sustainable development proponent William McDonough believes that “sustainable development is the conception and realization of environmentally sensitive and responsive expression as part of the evolving ecological matrix.”3

In this way, then, human activities can lead to an increase in sustainability. This is a new and powerful idea, but it complicates matters. Although many components of the global machine can change their form or function as a response to changing energy and nutrient flows, humans seem unique in their ability to understand these flows and change them for the better—that is, with the intent of benefiting both the human community and the long-term health of the ecosystems that sustain it.

As if the addition of a conscious party, humans, were not complication enough, the definition of sustainability adds one even more daunting complexity: time. Brundtland’s definition of sustainability includes an intergenerational responsibility. The long-term multigenerational effects of any decision must be considered before immediate needs are met. Coming up with solutions for immediate urban design problems that consider both humans and the long-term health of their environment can be a daunting enough task, but adding an intergenerational responsibility threatens to make such problem solving almost impossible. How can we deal, in our complex and multilayered democracies, with such challenges? Democratic public process models are needed wherein citizens can both understand these complex relationships and create ways to capitalize on them in their communities.

We Are Handcuffed by Our Methods

Our largely linear and mechanistic methods for solving local and even global problems seem ill suited to the task. For example, opposing camps of scientists are now debating the extent to which human activity is contributing to climate change. Both sides come armed with complex, sophisticated climate models. These models attempt to capture the “mechanics” of climate, assuming that climate is describable in mechanical terms. Newton lives on in these computer models, whatever their complexity. But the results remain inconclusive. Meanwhile, political leaders and those they represent still demand scientifically verifiable “proof” before they are willing to contemplate any new restrictions on the economy—proof that climate models can never supply, at least not before Greenland melts and the oceans expire.

John Lyle makes this point more simply: “The question is often asked: How much of this pollutant or that activity can the environment absorb before it becomes unacceptably damaging or life-threatening? This is like asking how many times one can beat a person over the head before he will die…. This is difficult to answer with any accuracy and usually not the most useful question anyway.”4

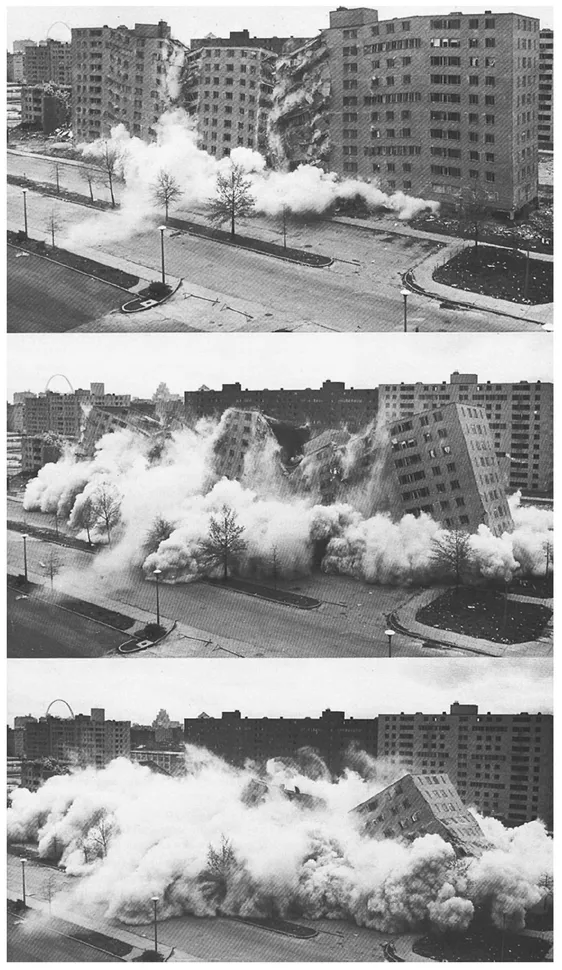

Methods That Fail Globally Fail More Spectacularly Locally

This same mechanistic thinking is observable at the municipal scale. The Pruitt Igoe housing complex in St. Louis, Missouri, built in the 1950s and abandoned in the early 1970s, is but one tragic example of this methodological failure.5 The Pruitt Igoe housing complex was designed to conform to French architectural theorist Le Corbusier’s elegant but narrow formulation for a modern urban utopia. Provide enough air and light for all citizens, he said, and all will be well. His formulation excluded other cultural, social, and behavioral influences. He missed, or chose to ignore, the intimacy of connection between people, buildings, and streets that Jane Jacobs so famously described in The Death and Life of Great American Cities.6 As a consequence, the project soon became uninhabitable and derelict.

French architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (pseud: Le Corbusier, 1887–1965) examines the model for his imagined “Radiant City.” Conceived in the 1920s, it would not be until the end of World War II that actual projects like this were built. In the United States, this kind of project was often used to house poor families displaced when their traditional neighborhoods were cleared for urban renewal or highway building projects.

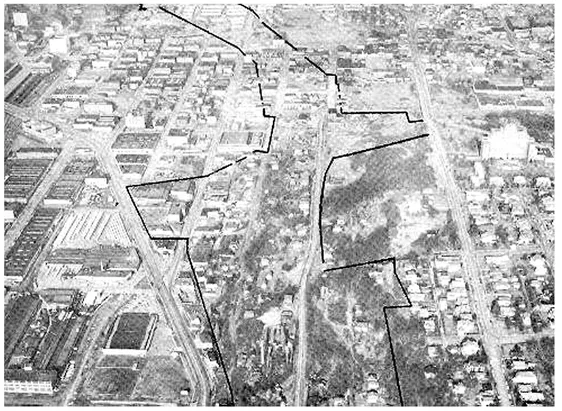

Even more tragically, at the same time Pruitt Igoe was going up, many of St. Louis’s most efficient and walkable neighborhoods were being torn down—all to make way for highways to farmlands that were soon to be suburbs. Each of these projects was a “rational” solution to a narrowly defined problem—one a solution to deal with a “housing” problem, and the other to deal with a “transportation” problem. The planners for each of these projects, probably quite brilliant within their own defined disciplines, did not (or could not) consider the connection between their two projects. Their linear methods and narrow problem definitions made it impossible to see that connection.

Aerial photograph showing the nearly completed clearing of inner-city lands for the construction of Interstate 70 in St. Louis, Missouri. Wide swaths of older inner-city neighborhoods were cleared during the highway building boom of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Among the consequences: divided neighborhoods in inner-city areas and easy access to the center city by car from the surrounding countryside.

These failures in St. Louis were failures of method. The narrow and mechanistic methods chosen, so effective for getting men on the moon and exploding atomic bombs, proved surprisingly ineffective for solving the smaller but more nuanced problems facing urban North America. To solve such layered and complex sustainability problems, a more inclusive method is required. A design charrette is nothing if not inclusive. A design charrette can handle both the physically quantifiable elements of the problem and those that cannot be quantified.

Working with this much complexity comes at a cost: in the face of so many variables, we can never be certain that we have found the perfect solution. Perfect solutions, in the sense that scientific methods require, are possible only for very narrowly defined problems containing a limited number of variables. Any method for creating and implementing sustainable urban designs must accept all relevant variables from all three realms—social, ecological, and economic. We believe that the sustainable urban design charrette method meets this criterion. We further believe that sustainability problems, by their very nature, demand an inclusive and synthetic problem-solving process—precisely because they are divergent problems of the kind discussed below.

The Pruitt Igoe housing project was demolished by the St. Louis Housing Authority in 1972, after only twenty years of occupation. Despite conforming to Le Corbusier’s principles, providing light, air, and green for every resident, it proved uninhabitable. Jane Jacobs and others took Le Corbusier to task for ignoring the organic relationship between people and the cities they inhabit, embodied in the urban syntax of street, stoop, entry, and parlor. None of these features are part of the Radiant City vision.

Sustainability Is a Divergent Problem, Not a Convergent Problem

Although they have phrased it differently, various philosophers, from Aristotle to Merleau-Ponty, have discussed the existence of two different kinds of problems: the convergent and the divergent. E. F. Schumacher, the British economist famous for his 1973 book Small Is Beautiful,7 describes these concepts in an accessible and succinct way in his 1977 book A Guide for the Perplexed. As he put it, convergent problems tend toward a single and perfect solution: the problem is described, evidence is collected, and the problem is solved. He uses the invention of the bicycle as his example, suggesting that it provides an elegant solution for the problem of “how to make a two-wheeled man-powered means of transportation.”

Schumacher suggests, however, that many other problems are more complicated. For example, “the human problem of how to educate our children” has two apparently supportable but opposing solutions. One solution would have us provide an atmosphere of discipline sufficient for experts to transfer information to children. If we are actively seeking the perfect solution implicit in any convergent problem, we might conclude that the perfect school would be one characterized by perfect discipline—that is, a prison. On the other hand, equally persuasive are those who find, on the basis of good evidence, that children respond best to freedom and find their own way to knowledge. In this case, the perfect school would be one that is characterized by perfect freedom—that is, “a kind of lunatic asylum.” How, asks Schumacher, are we to resolve this contradiction?

There is no solution. And yet some educators are better than others. How does this come about? One way to find out is to ask them. If we explained to them our philosophical difficulties, they might show signs of irritation with this intellectual approach. “Look here,” they might say, “all this is far too clever for me. The point is: You must love the little horrors.” Love, empathy, participation mystique , understating, compassion—these are faculties of a higher order than those required for the implementation of any policy of discipline or of freedom. To mobilize these higher faculties or forces, to have them available not simply ...

Table of contents

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Charrette Theory for People in a Hurry

- 2. Two Kinds of Charrettes

- 3. The Design Brief

- 4. The Nine Rules for a Good Charrette

- 5. The Workshops

- 6. The Charrette

- 7. After the Charrette

- 1 - Case Study The East Clayton Sustainable Community Design Charrette

- 2 - Case Study The Damascus Area sign Workshop

- Appendix: - Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities Links Page

- Endnotes

- Index

- Island Press Board of Directors