- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

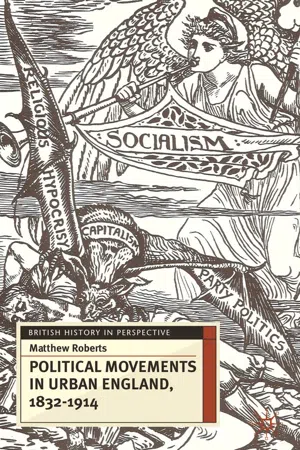

Political Movements in Urban England, 1832-1914

About this book

A critical introduction to the mass political movements that came of age in urban England between the Great Reform Act of 1832 and the start of World War One. Roberts provides a guide to the new approaches to topics such as Chartism, parliamentary reform, Gladstonian Liberalism, popular Conservatism and the independent Labour movement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Political Movements in Urban England, 1832-1914 by Matthew Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: Citizenship, the Franchise and Electoral Culture

In a letter to The Times, published on 30 July 1884, the trades unionist George Potter asked: ‘If fitness is a matter of citizenship, are we not all Britons?’ Potter went on to demonstrate that, in his opinion, many allegedly ‘fit’ Britons were, in fact, being denied citizenship (by which he meant the vote). Debates about citizenship, and who was deemed ‘fit’ to have that status conferred upon them, were central to the politics of Victorian Britain. The concept of citizenship might appear somewhat anachronistic in relation to nineteenth-century Britain – or even altogether alien. This is because citizenship has all too often been defined narrowly as a legal category that denotes membership of a national community, the acme of which is seen to be the possession of a passport. Yet, as new studies have made clear, citizenship needs to be defined more expansively as a status that mediates the relationship between individuals and the political community.1 Citizenship can be understood in a British context as the mechanism whereby formal limits are placed on subjecthood (that is, the sovereign power of the state over its subjects) by allowing people to play a part in government. Hence the importance attached to the vote, especially by those who did not enjoy the privilege.2 As the radical Joseph Chamberlain tellingly observed in the debates on the Third Reform Act of 1884–85, voting was ‘the first political right of citizenship’.3

The three major reform acts (1832, 1867 and 1884), and the public debates to which they gave rise, were concerned with the question of what sorts of people should be included in – and who should be excluded from – the political life of the nation.4 Put simply: who should be allowed to vote, and on what basis? These seemingly straightforward questions ranked amongst the most controversial of issues in modern British politics. This chapter explores how the ‘political citizen’ was defined by the state. It also examines ‘official’ and ‘popular’ understandings of what it meant to have the vote between the First and Third reform acts. In so doing, this chapter introduces some of the main principles and assumptions that underpinned the evolving relationship between politics and the people in the nineteenth century. These principles transcended political divisions, though individual political movements tended to interpret these in different ways, as will become clearer in later chapters.

Electoral Citizenship

By the early nineteenth century, a model of political citizenship had emerged that was based on a fusion of English legal precedent and continental theories of classical republicanism. That model would survive largely intact until 1914, although the structural integrity of that model was weakened in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This model of citizenship, as with the so-called ‘English constitution’ from which it issued, had evolved somewhat haphazardly over time. Its unwieldy nature was due to the absence of a formal written constitution, such as existed in France and the United States of America. However, the Constitution was no less real for that. Discussions about the Constitution – and, more importantly, what was thought to be constitutional – saturated the language and practice of popular politics.5

Underpinning this model of citizenship was the notion of ‘independence’, a notion reinforced by ideas drawn from classical republicanism. These ideas had been rediscovered by the Renaissance civic humanists of fifteenth and sixteenth century Florence who wished to see a return to the classical civic ideal of selfless participation in public life for the wider public good.

This civic humanist creed was transported into Britain as a response to the breakdown of constituted authority in the Civil War period. Ideas of republican liberty did not displace the indigenous ideology of Britain’s unwritten constitution; rather, it was grafted onto that ideology. The Civil War period had underlined how much English liberty was located in a shifting ground of ‘immemorial custom’ that had to be continuously interpreted and reinterpreted. In turn, this necessitated a kind of active, republican citizenship as these customs had to be preserved, refined and transmitted, especially in the face of contestation.6

According to standard historical interpretations, this neo-classical republican model of citizenship was displaced in the late eighteenth century and, by the nineteenth century, had been replaced by a liberal model. In contrast to neo-classical models of citizenship, which stressed duty, this liberal model emphasized abstract individual rights. However, a growing body of research suggests that republicanism was not entirely displaced by liberalism, and that it continued to shape notions of corruption, constitutionalism, civic duty and citizenship well into the nineteenth century.7 As with their Florentine predecessors, English politicians, especially radicals and reformers, were concerned with creating the conditions for a durable republic of virtuous citizens. The problem was that reformers could not agree on what constituted a ‘virtuous citizen’.

Republican ideas of citizenship also merged with English legal customs relating to property. Independence was the prerequisite for citizenship, and this was the exclusive preserve of male propertied householders. If the possession of property, as opposed to one’s gender, was the cardinal criterion for political participation, the English legal system forged a very close association between the two. Under English common law, single and widowed women could own property on the same basis as men. As soon as women married, however, their legal existence was subsumed by their husbands, and this included their property. This legal disability was only partially overturned by the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882.8 Thus, it was widely accepted that only men in the condition of independence could and should participate in public life. Those who were in a state of ‘dependency’ would lack the necessary virtues – reason, temperament, education and a material stake in society – to resist the corruption and bribery that perennially threatened to reduce the political system to a state of servile effeminacy. Dependency could assume a number of forms: a client upon a patron, a tenant upon a landlord, a servant upon a master, a woman upon a man. Obligation and dependency were associated with femininity and effeminacy, and to be labelled as such was politically disempowering.9 Independence was also contingent on the ability to support and defend one’s dependents. This explains why the ideal citizen was usually conceived of as the head of a household. In a somewhat circular argument, the independence of men was underscored by having dependents in the form of wives, sisters, sons and daughters.10 As the Liberal J. A. Roebuck argued in the parliamentary debates on the Second Reform Act of 1867, ‘if a man has a settled house, in which he has lived with his family for a number of years, you have a man who has given hostages to the state, and you have in these circumstances a guarantee for that man’s virtue’.11

The independent man was expected to exhibit certain characteristics in his behaviour: notably sincerity, assertiveness and straightforwardness. Embodying these characteristics ‘fitted’ one for political citizenship. Here is Gladstone, soon to be leader of the Liberal party, on the occasion of his much quoted House of Commons speech of May 1864 on the moral entitlement of respectable working men to the franchise: ‘What are the qualities which fit a man for the exercise of a privilege such as the franchise? Self-command, self-control, respect for order, patience under suffering, confidence in the law, regard for superiors’. Earlier in the speech, Gladstone had declared that men who possessed such qualities ‘are fit to discharge the duties of citizenship’.12 Demonstrating a virtuous masculine self was the desideratum for enfranchisement.

For much of the eighteenth century, political commentators had mainly been concerned with ensuring the independence of public servants as a means to resist webs of corruption surrounding the King and his ministers. Governments at this time relied heavily on dispensing patronage to create and maintain parliamentary majorities. This gave rise to the ‘country-party’ ideology and the associated phenomenon of ‘electoral independence’. ‘Country-party’ ideology was originally developed by opposition Whigs and later adopted by the Anglican tory squirearchy. It was the response by these ‘outs’ to their exclusion from power by the party of the ‘court’ (the ‘ins’ – the exclusive and corrupt recipients of royal patronage). This ‘country’ ideology maintained that only independent men who were free of this patronage network were able to restore balance and virtue to the polity. Hence the redemptive faith that Georgian reformers placed in the ‘independent MP’, so-called because of his public repudiation of patronage. Under the democratizing impact of the American and French revolutions and the rise of popular radicalism, the focus shifted from this exclusive preoccupation with the character of public men to the qualities of the electorate as well. Independence came to be thought of in more inclusive ways. The ability to support one’s household and the possession of basic manly qualities such as sincerity and self-assertion became the criteria for political participation. This growing inclusiveness was facilitated by the various reform acts of the nineteenth century. As Matthew McCormack has argued: ‘the story of the British parliamentary reform movement can be told in terms of how reformers gradually came to associate ever-humbler groups of men with “independence”, until manhood suffrage made the identification complete’.13 Whereas only a minority of men met these standards in 1832, subsequent generations of reformers contested, aspired to or appropriated its terms until – by the Third Reform Act of 1884–85 – citizenship was symbolically synonymous with adult masculinity.14

Electors were expected to act the part of the ‘independent man’. It was here that notions of ‘electoral independence’ came into play. This was the means by which electors defended local privileges and challenged abuses of power, such as those wielded by dictatorial MPs. This could take the form of voting against the instructions of patrons or ‘interests’, or by nominating a candidate who was independent of, and therefore opposed to, those interests. Historians have usually associated electoral independence with the pre-1832 ‘unreformed’ political system. A growing body of evidence points to the survival of these eighteenth-century traditions of ‘country’ patriotism and electoral independence until the end of the nineteenth century.15 Part of the reason for this was their flexibility and inclusiveness. Originally an anti-party creed, this ‘country-party ideology’ was subsequently drawn on and adapted by the whole political spectrum.

Only genuinely independent citizens, then, could be entrusted with the franchise. According to the tacit theory of political representation, most Georgians and Victorians conceived of the franchise not as a right but as a trust. Those in possession of the franchise had a responsibility to the wider interests of the community. To those who were devout, their vote was a sacred trust conferred on them by God – to whom they were also answerable.16 According to this theory, independent men could be trusted to elect ‘fit and proper persons’ who would honourably discharge the duties of public office in the interests of all. This model of citizenship was thus bound up with one of the fundamental principles of the political system: ‘virtual representation’. This held that even those people without the vote were represented ‘virtually’ by the enfranchised portion of the community.17 Naturally, it was the perennial complaint of radicals and reformers that ‘virtual representation’ simply did not work as some electors patently did vote for their own selfish interests, hence the charges of ‘Old Corruption’ (the name given to the idle, tax-eating aristocrats and their placemen, who monopolized control of the political, religious and military establishment) and the need for a wider, more democratic franchise.

Debates about who constituted the political citizen were not only concerned with who could vote, but also with the act of voting. The electoral contest itself was an open affair, with polling usually lasting two days after 1832, and one day after 1835 in the boroughs. Elections were part of the entertainment culture of the day in which the whole local community took part – electors and non-electors, especially in the first half of the nineteenth century. As Frank O’Gorman has shown in his re-creation of electoral culture between 1780 and 1860, the whole campaign from beginning to end (usually spanning a fortnight) was structured by rituals.18 The commencement of the campaign was marked by the formal entry of the candidates into the constituency to be greeted by an assembled crowd. Many candidates would then conduct a door-to-door canvass – aided by an entourage of the local elite – to court, flatter and possibly bribe potential voters and their families. The campaign was likely to be punctuated by a series of ‘treating rituals’, such as dinners and breakfasts. The focal point of the contest was the hustings – raised wooden platforms on which compartments or rooms were often erected – usually close to places of civic importance. It was here that candidates made daily speeches ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Citizenship, the Franchise and Electoral Culture

- Chapter 2: Radicalism in the Age of the Chartists

- Chapter 3: The Culture and ‘Failure’ of Radicalism

- Chapter 4: The Making of Mid-Victorian Popular Liberalism

- Chapter 5: Post-Chartist Radicalism and the (Un)making of Popular Liberalism

- Chapter 6: Rethinking the ‘Transformation’ of Popular Conservatism

- Chapter 7: Defining and Debating Popular Conservatism

- Chapter 8: The Decline of Liberalism and the Rise of Labour I: A Narrative

- Chapter 9: The Decline of Liberalism and the Rise of Labour II: The Debate

- Chapter 10: The Modernization of Popular Politics

- Notes

- References

- Index