![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

VIVIEN LOWNDES, DAVID MARSH AND GERRY STOKER

This book introduces the theories and methods that political scientists use, which we think tells us a great deal about the nature of political science. To us, political science is best defined in terms of what political scientists do. Of course, there are thousands of political scientists around the world and we have tried to capture and clarify the variety of ways they seek to understand, explore and analyse the complex processes of politics in the modern era. We are interested in how they differ in their approach, but also in what they share. Our book identifies nine approaches used by political scientists and then explores some of the specific research methods, which are used in different combinations by scholars from these different approaches.

All disciplines tend to be chaotic, to some extent, in their development (Abbott, 2001) and political science is certainly no exception. However, we would argue that the variety of approaches and debates explored in this book are a reflection of its richness and growing maturity. When trying to understand something as complex, contingent and chaotic as politics, it is not surprising that academics have developed a great variety of approaches. For those studying the discipline for the first time, it may be disconcerting that there is no agreed approach or method of study. Indeed, as we shall see, there is not even agreement about the nature of politics itself. But, we argue that political scientists should celebrate diversity, rather than see it as a problem. The Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon makes a powerful case for a plurality of approaches, which he sees as underpinning the scientist’s commitment to constant questioning and searching for understanding:

I am a great believer in pluralism in science. Any direction you proceed in has a very high a priori probability of being wrong; so it is good if other people are exploring in other directions – perhaps one of them will be on the right track. (Simon, 1992: 21)

Studying politics involves making an active selection among a variety of approaches and methods; this book provides students and researchers with the capacity to make informed choices. However, whatever your choice, we hope to encourage you to keep an open mind and consider whether some other route might yet yield better results.

The study of politics can trace its origins at least as far back as Plato (Almond, 1996); as such, it has a rich heritage and a substantial base on which to grow and develop. More specifically, it has been an academic discipline for just over a century; the American Political Science Association was formed in 1903 and other national associations followed. As Goodin and Klingemann (1996) argue, in the last few decades the discipline has become a genuinely international enterprise. Excellent and challenging political science is produced in many countries and this book reflects the internationalisation of the discipline in two senses. First, we have authors who are based in the UK, elsewhere in Europe, the USA and Australia. Second, many of the illustrations and examples provided by authors offer up experiences from a range of countries, or provide a global perspective. Our authors draw on experiences from around the world and relate domestic political science concerns to those of international relations. This makes sense in an ever more globalised world.

The increasing influence of global forces in our everyday lives makes globalisation a central feature of the modern era. Debates about collective decisions which we observe at the international, national and local levels take place through a dynamic of governance (Chhotray and Stoker, 2009). In the world of governance, outcomes are not determined by cohesive, unified nation states or formal institutional arrangements. Rather, they involve individual and collective actors both inside and beyond the state, who operate via complex and varied networks. In addition, the gap between domestic politics and international relations has narrowed, with domestic politics increasingly influenced by transnational forces. Migration, human rights, issues of global warming, pandemics of ill-health and the challenges of energy provision cannot, for example, be contained or addressed within national boundaries alone.

A new world politics (different from ‘international relations’) is emerging, in which non-state actors play a vital role, alongside nation states (Cerny, 2010). The study of world politics is not a separate enterprise, focused on the study of the diplomatic, military and strategic activities of nation states. Non-state and international institutions, at the very least, provide a check to the battle between nation states. At the same time, the role of cities and sub-national regions has expanded, as they make links across national borders in pursuit of economic investment in a global marketplace, while seeking also to collaborate in tackling complex governance challenges (such as migration and global warming), which do not themselves respect national boundaries. Indeed, some analysts go as far as to suggest that cities may become the ‘new sovereign’ in international orders in which both nation states and multilateral bodies are challenged (Barber, 2013; Katz and Bradley, 2013).

Moreover, the breadth of the issues to be addressed at the international level has extended into a range of previously domestic concerns, with a focus on financial, employment, health, human rights and poverty reduction issues. At the same time, the nature of politics at the international level has become more politically driven, through bargaining, hegemonic influence and soft power – rather than driven solely by military prowess and economic strength, although the latter remain important. However, the questions to be asked about politics at local, national and global levels are fundamentally the same. How is power exercised to determine outcomes? What are the roles of competing interests and identities? How is coordination and cooperation achieved to achieve shared purposes? How are issues of justice and fairness of outcome to be identified and understood? Consequently, the examples and illustrations of the academic study of politics in this book reflect the growing interlinkage of domestic politics and international relations.

This book focuses upon the ways of thinking or theorising offered by political scientists and the methods they are using to discover more about the subject at the beginning of the twenty-first century. It is inevitable that the book will neither be fully comprehensive in its coverage of political science, nor able to provide sufficient depth in approaching all of the issues that are considered. Rather, our intention is to provide an introduction to the main approaches to political science and a balanced assessment of some of the debates and disagreements that have characterised a discipline with several thousand years of history behind it, and many thousands of practitioners in the modern world.

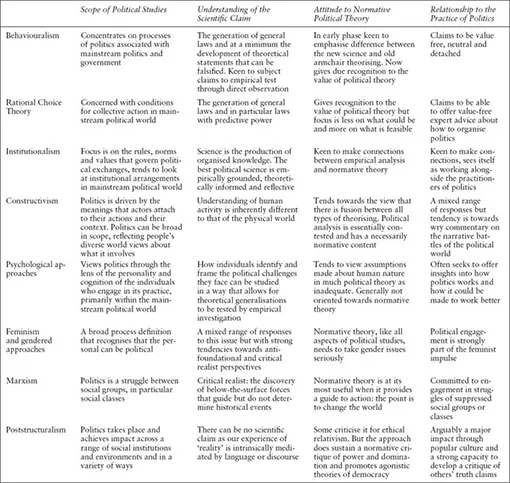

The book is divided into two broad parts. The chapters in the first part map the broad ways of approaching political science that have had, and are likely to have, a major effect on the development of political science: behaviouralism, rational choice theory, institutionalism, constuctivism, feminism, Marxism, poststructuralism and political psychology (see Table 1.1). Each of the approaches focuses upon a set of issues, understandings and practices that define a particular way of doing political science. We asked each of our authors not simply to advocate their approach, but also to explore criticisms of that approach. In this respect, we hope that each author offers a robust, but self-aware and critical, understanding of his or her way of doing political science. We have also asked authors to provide ‘worked examples’ of their approach in action within political science. As such, our understanding of theory is neither abstract, nor abstruse. In our experience, students often regard theory as a burden, something that gets in the way of studying real-life politics. We want to show how theory facilitates, rather than obstructs. The approaches discussed in this book show how theory frames new questions and provides important leverage for understanding political puzzles. Theory allows us to see things we wouldn’t otherwise see. Each of our approaches could be seen as a different pair of spectacles; when we put them on our focus changes, and different aspects of a phenomenon come into view. Beyond the academy, political science not only influences the world of politics and governance by providing evidence from research, but also has the potential to shape the way in which political actors themselves regard their opportunities and develop their strategies (as reflected, for example, in the influence of rational choice theory on many right-wing governments, or of institutional approaches like governance on transnational bodies and development agencies).

Table 1.1 Approaches to political science

The final chapter in this first part of the book explores the issue of normative theory, although it is important to recognise that there are normative elements in all approaches. This is one of the most traditional approaches to political science, but it remains relevant today. Political science should be (and is) interested in understanding both ‘what is’, usually seen as the empirical dimension, and also ‘what should be’, the normative dimension. Further, we agree with Baubock (2008: 40) that ‘empirical research can be guided by normative theory; and normative theory can be improved by empirical research’. The distinctiveness of normative theory is clear, but the dialogue between normative theory and the other approaches is crucial. Empirical theorists can benefit from the specification and clarification of arguments provided by normative theory and, in our view, normative theorists need to look to empirical research, as well as hypothetical arguments, to help support their case. Moreover, the emergence of new empirically driven theoretical insights, for example those associated with the governance school (Chhotray and Stoker, 2009), may open up new issues and challenges for normative theory.

The second half of the book moves to issues of methodology and research design. We begin, in Chapter 11, by introducing debates about the ontological and epistemological positions which shape our answers to the crucial questions of what we study, how we study it and, most significantly, what we can claim on the basis of our research. These ontological and epistemological positions also underpin what in Chapter 12 we term meta-theoretical issues, specifically, the relationships between structure and agency, the material and the ideational and continuity and change, which cut across all the different approaches.

Subsequently, in Chapter 13, we turn to the important question of how we design our research project or programme. Finally, in the last five substantive chapters we examine different research methods. We examine the range of both qualitative and quantitative techniques that are available and how these techniques can be combined in meeting the challenge of research design, before moving on to consider the potential and limitations of the comparative (often cross-national) method for understanding political phenomena. We then turn to two methods which have come to prominence in political science more recently, experimental methods and ‘big data’. In an increasingly digital age enormous volumes of data are generated outside the academy and can be used to reveal patterns of human behaviour and interaction that have political significance. The final chapter in the book assesses the utility of political science not in terms of its methods, but by examining whether it has anything relevant to say to policymakers, public servants and, most importantly, citizens.

In the remainder of this introductory chapter we aim to provide an analysis of the term ‘political’ and some reflections on justifications of the term ‘scientific’ to describe its academic study. We close by returning to the issue of variety within political science by arguing that diversity should be a cause of celebration rather than concern.

What is politics? What is it that political scientists study?

When people say they ‘study politics’ they are making an ontological statement because, within that statement, there is an implicit understanding of what the polity is made up of, and its general nature. They are also making a statement that requires some clarification. In any introduction to a subject it is important to address the focus of its analytical attention. So, simply put, we should be able to answer the question: what is the nature of the political that political scientists claim to study? A discipline, you might think, would have a clear sense of its terrain of enquiry. Interestingly, that is not the case in respect of political science. Just as there are differences of approach to the subject, so there are differences about the terrain of study.

As Hay (2002: chapter 2) argues, ontological questions are about what is and what exists. Ontology asks: what’s there to know about? Although a great variety of ontological questions can be posed (discussed in Chapters 11 and 12), a key concern for political scientists relates to the nature of the political. There are two broad approaches to defining the political, seeing politics in terms of an arena or a process (Leftwich, 1984; Hay, 2002). An arena definition regards politics as occurring within certain limited ‘arenas’, initially involving a focus upon Parliament, the executive, the public service, political parties, interest groups and elections, although this was later expanded to include the judiciary, army and police. Here, political scientists, especially behaviouralists but also rational choice theorists and some institutionalists, focus upon the formal operation of politics in the world of government and those who seek to influence it. This approach to the political makes a lot of sense and obviously relates to some everyday understandings. For example, when people say they are fed up or bored with politics, they usually mean that they have been turned off by the behaviour or performance of those politicians most directly involved in the traditional political arena.

The other definition of ‘politics’, a process definition, is much looser than the arena one (Leftwich, 2004: 3) and reflects the idea that power is inscribed in all social processes (for example, in the family and the schoolroom). This broader definition of the political is particularly associated with feminism, constructivism, poststructuralism and Marxism. For feminists in particular there has been much emphasis on the idea that the ‘personal is political’ (Hanisch, 1969). This mantra partly originated in debates about violence against women in the home, which had traditionally been seen as ‘non-political’, because they occurred in the private rather than the public realm. Indeed, in the UK at least, the police, historically, referred to such violence as ‘a domestic’, and therefore not their concern. The feminist argument, in contrast, was that such violence reflected a power relationship and was inherently ‘political’.

Marxists have also generally preferred a definition of politics that sees it as a reflection of a wider struggle between social classes in society. Politics in capitalist systems involves a struggle to assert the interest of the proletariat (the disadvantaged) in a system in which the state forwards the interests of the ruling class. Constructivists tend to see politics as a process conducted in a range of arenas, with the main struggles around political identity (hence the focus on identity politics). Poststructuralists take this position further, arguing that politics is not ‘contained’ within a single structure of domination; rather, power is diffused throughout social institutions and processes, and even inscribed in people’s bodies.

Process definitions are usually criticised by those who adopt arena definitions, because of what is termed ‘conceptual stretching’ or the ‘boundary problem’ (see Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Hooghe, 2014). If politics occurs in all social interactions between individuals, then we are in danger of seeing everything as political, so that there is no separation between the ‘political’ and the ‘social’. The alarm bells might be ringing here since it appears that political scientists cannot even agree about the subject matter of their discipline. Yet our view is that both ‘arena’ and ‘process’ definitions have their value; indeed, the relationship between process and arena definitions may be best seen as a duality, that is interactive and iterative, rather than a dualism, or an either/ or (Rowe et al., 2017). Moreover, all of the different approaches to political science we identify would at least recognise that politics is about power and that we need to widen significantly an arena definition of politics.

Goodin and Klingemann (1996: 7) suggest that a broad consensus could be built around a definition of politics along the lines: ‘the constrained use of social power.’ The political process is about collective choice, without simple resort to force or violence, although it does not exclude at least the threat of those options. It is about what shapes and constrains those choices and the use of power and its consequences. It would cover unintended as well as intended acts, and passive as well as active practices. Politics enables individuals or groups to do some things that they would not otherwise be able to do, while it also constrains individuals or groups from doing what they might otherwise do. Although the different approaches to political science may have their own take on a definition of politics, contesting how exactly power is exercised or practised, they might accept Goodin and Klingemann’s broad definition.

It is clear that politics is much broader than what governments do, but there is still something especially significant about political processes that are, or could be, considered to be part of the public domain. In a pragmatic sense, it is probably true to say that most political scientists tend to concentrate their efforts in terms of analysis and research on the more collective and public elements of power struggles. But, it is important that we develop a sense of the collective or public arena that takes us beyond the narrow machinations of the political elite.

What is a scientific approach to politics?

As Goodin and Klingemann (1996: 9) comment, ‘much ink has been spilt over the question of whether, or in what sense, the study of politics is or is not truly a science. The answer largely depends upon how much one tr...