![]()

Part One

Getting Started

![]()

1 Who is this Book for?

Getting acquainted

Since you have opened this book we guess you have some interest in computer programming, even if it’s just curiosity.

As authors, we cannot be sure exactly who you are but we might guess that you are a student either taking a programming course or thinking about taking one? Alternatively, you might be the parent of such a student, or maybe you teach programming? Still not right? Then perhaps you are just someone who is interested in finding out what programming is all about. Whichever of those groups you belong to, you are one of the people we are primarily writing for: students in the final two years of school, in Further Education colleges or the first year of university; and those who support such students. But we hope this book might also be useful to others outside those boundaries.

This book is about how to go about learning programming effectively. We should stress at this early stage that it is not a tutorial for a particular programming language. Instead, it focuses on some of the skills, attitudes and techniques required to study programming successfully. We won’t assume that you know anything about programming already, but we’ll begin by telling you what programming is and how to get started. We’ll also explain how studying programming may be different from studying other subjects, what pitfalls to avoid, and much more.

Who are we then, and why did we write this book? We are all computer scientists and teachers of programming. We enjoy programming and enjoy introducing it to others. When we were sitting around discussing our teaching, we discovered that even though we were teaching different programming topics, there were ideas and techniques that we all discussed with our students. These were common to all the programming courses but were different from what was needed in other subjects. When we looked around for a book that covered the material we were surprised not to find one; and so we set about writing this.

Picking your route

Many books are designed to be read straight through, from page 1 of Chapter 1 to the end. You would not normally read a novel any other way, for instance, unless you are one of those who peek at the last page early! But, of course, books are rarely written in a linear fashion, and most novels have multiple themes that run through them, with characters or plots that come and go to provide variation of pacing and interest.

We hope you will find that there is a variety of ways you could read this book. If you wish, you can read each chapter in turn, from Chapter 1 through to Chapter 16. On the other hand, you might like to take the chapters in a pick-and-mix fashion – following a route that fits in with your existing knowledge and your individual approach to study.

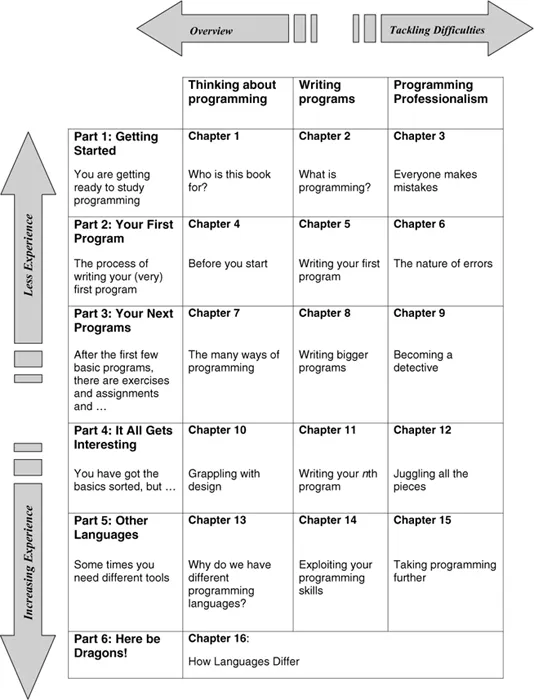

In our minds there are some recurrent themes that run through this book – rather like the warp and weft fibres that run through a fabric. You can think of the book as being structured into five parts, each of which consists of three chapters. Each part relates to a stage in the development of a programmer, from Getting Started (Chapters 1–3), to moving on to Your First Program (Chapters 4–6), then exploring Your Next Programs (Chapters 7–9), to find that It All Gets Interesting (Chapters 10–12) and then learning about Other Languages (Chapters 13–15). These parts make good sense if read in order but each can also be read independently of the others. For instance, if you’ve already written quite a few programs, you might want to start with Your Next Programs or Other Languages. You can dip in at the point that suits you. Whatever your level of experience you will probably find that there are ideas that you haven’t come across before in most of the chapters.

Another way that we have structured the book is to use three themes that recur in each part: ‘Thinking about Programming’ (Chapters 1, 4, 7, 10 and 13), ‘Writing Programs’ (Chapters 2, 5, 8, 11 and 14) and ‘Programming Professionalism’ (Chapters 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15). So if you want to spend some time just thinking about programming issues you can dip into the first chapter of each part. Or you could focus on practical programming issues and take the second chapter in each of the five parts.

We have tried to capture the essence of these structures in the diagram shown in Figure 1.1. As you can see, the final chapter, ‘Here be Dragons!’ is a little different and stands outside the other structures. It takes you into the land beyond regular programming tasks and explores the fascinating world of programming paradigms. If you want to know what they are, you could even make that your starting point.

The recurrent themes we have highlighted serve to illustrate an important principle about any subject, not just programming: as you learn more and more about a subject, you will find yourself again and again revisiting topics that you have already encountered, and refining and deepening your understanding of them. You will never stop learning.

So, that’s it with the first overview. We hope you enjoy the rest of the book!

![]()

2 What is Programming?

One of the things about programming that can make it appear difficult or inaccessible at first sight is the languages that are used to write computer programs. We are going to remove some of this mystique. Many programming languages are odd mixes of mathematical symbols, punctuation marks and ordinary words. In fact, programming languages are actually very simple in nature – far simpler than any human language – but this simplicity is obscured by our lack of familiarity with them. We are going to find a way through that obscurity by looking at everyday human activities and see how they are similar to, and different from, programming. By seeing the similarities between everyday life and problems we would use a computer to solve, we will begin to understand how computers are programmed and, hence, why programming languages often look like they do.

What it means to be programmed

If we say that someone or something has been ‘programmed’ then we usually mean that they will do something slavishly – without thinking – possibly doing it over and over again. That idea fits quite well with the concept of computers being programmed. Computers cannot think for themselves; they can only do what they have been instructed to do, and they cannot vary from the instructions they have been given.

Most of the time, this predictability is a good thing. It means that the miniature computer that controls a washing machine goes through its cycles in the right order, and turns our dirty clothes into clean and rinsed clothes; that banks keep an accurate record of credits and debits on our accounts; that aircraft carry us safely on holiday and back again; that word processors don’t scramble our files.

However, sometimes that lack of an ability to think for itself means that a computer will go ahead and carry out its programmed task even when it isn’t appropriate. For instance, a washing machine will go through its cycles even when there are no clothes in it. A person would see that this is pointless, but a computer in a washing machine does not.

Much of the skill in programming is about creating a set of instructions that will tell an otherwise mindless computer what you want it to do. That is a very powerful idea, because computers are much better at doing some things than we are. If we can find an appropriate set of instructions for a problem we want to solve or a task we want to perform, then there is a good chance that we can hand that task or problem over to a computer and let it get on with it for us. That is one reason why computers have become so common in everyday life. In order to successfully give instructions to a computer, we need to understand what kinds of instruction a computer can deal with. That means we will need to discuss ‘programming languages’ – languages used to program computers.

However, before we do that, let’s explore a little more about the nature of ‘programming’, because we shall see that most of us already know a good deal about it, even if we have never consciously been involved with computer programs before.

Task-oriented languages

For centuries people have been creating ‘languages’ to express solutions to tasks, or to capture descriptions of things, in such a way that other people can reproduce them accurately. A non-computer programming language familiar to most people is musical notation (Figure 2.1). Even if you cannot read music, you will probably be aware of the look of a piece of music. For hundreds of years, musicians have used various forms of notation to communicate what notes to play, what order to play them in, how long to make each note last, whether to repeat a particular section, and so on. Such notations have proven to be very effective because anyone who can understand the notation and has sufficient skill on an appropriate instrument would be able to reproduce a composer’s tune.

Of course, to music lovers and aficionados, the dots on the page really only communicate a part of the story. What they don’t describe effectively is any sense of emotion or artistic expression, and two musicians playing from identical manuscripts may well create two significantly different performances. Once again, we have an example of the difference between slavishly following a set of instructions (as a computer would) and the way that people can think beyond the bare notes on a page. Nevertheless, for our purposes, musical notations provide a convenient analogy for computer programming languages, in the way that they capture a set of instructions that ...