![]()

1

Backstory

![]()

1

Introduction

“A Trampoline for the Imagination”

The true value of art is a function of its power as a liberating revelation.

René Magritte1

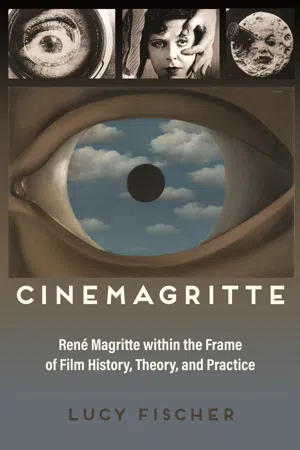

In this book, I investigate the connections between the great Belgian Surrealist/Modernist painter René Magritte (1898–1967) and the cinema. I seek to do so in a variety of ways—by discussing the scant observations that critics have made on the topic, exploring art documentaries about Magritte, investigating explicit cinematic homages to the painter, analyzing Magritte’s amateur movies, examining the broader scholarship on painting and film, and, most notably, surfacing what I deem to be “resonances” between his oeuvre and diverse films.

I choose the word resonance carefully because in conceiving it I am not generally claiming the direct influence of Magritte’s work on the movies or vice versa (though instances of this do occur). Rather, film history is inflected by many of the thematic discourses, conceptual issues, and iconographic tropes that Magritte routinely engaged—not surprising, since he and cinema came of age in and the same era (the early twentieth century). As Xavier Canonne writes, “The Surrealists were born with the movies.”2 Such parallels between Magritte’s work and the cinema exist because the artist’s creative interests involved subjects having direct relevance to film theory and practice—framing, scale, montage, illusionism, the gaze, theatricality, point of view, the face, and the status of objects. In cataloging these issues, I am reminded of what Magritte once said about the cinema in a letter to a friend—that he used it as a “trampoline for the imagination,” helping him to conceive his art.3 I will honor but reverse Magritte’s process, using his work as a creative jumping-off point for considering film.

In my choice of the term resonance, I am encouraged by its use by art historian A. M. Hammacher who applied it to Magritte’s work. He states: “Magritte attempted, as it were, to achieve a controlled resonance in his work. After he had finished a painting, it set up a resonance within him. . . . Magritte probably attached more than usual importance to having people feel the right kind of resonance. That he could do anything about this himself was an illusion; the others were the critics, the art historians, the museums, the art dealers, the collectors, who play their own game with a variety of intentions.”4 My intentions are to take seriously the resonances of Magritte’s work and foreground their implications for film history, theory, and practice.

Why Magritte?

But one may ask: Why choose Magritte out of all possible artists? I would assert that as one of the central painters of the Modernist era, he deserves more attention than the paltry consideration he has received in the annals of film studies. I would not make such a claim about many others. While the styles of Pablo Picasso or Piet Mondrian, for instance, may have relevance to experimental cinema, their methodologies do not readily apply to the dramatic fiction film. Magritte’s work, on the other hand, has ties to both cinematic modes—avant-garde and mainstream. Furthermore, while one can imagine a biopic about an artist like Edward Munch or imagery marked by his visual sensibility, one cannot conceive of a unique conceptual stance that cinema might inherit from him—while, with Magritte, one can.

This is so because Magritte considered himself a philosopher more than an aesthete. As Ellen Handler Spitz states, his paintings “are questions as well as paintings, or paintings as questions. . . . [T]hey illustrate links between the abstract and the personal, the paradoxical and the perverse.”5 Some of the topics she asserts he confronts are: “how things living differ (and yet do not differ) from things dead; how important objects can appear small and insignificant (while others, when charged with strong feeling loom large); how looking differs from experiencing; how art differs from life; how the same object that frightens and angers us at one moment can seem funny or absurd the next; how the concrete can become suddenly abstract and the abstract all too horribly concrete.”6 Magritte’s own words support this view. As he states, “My paintings are visible thoughts.”7 In fact, he conceived of his art as solving a series of “problems.” As he notes (in rather awkward language): “Any object, taken as a question of a problem . . . and the right answer discovered by searching for the object that is secretly connected to the first . . . give, when brought together, a new knowledge.”8 One such search involved doors. As Magritte observes: “The problem of the door called for an opening that someone could go through. In La Réponse imprévue [The Unexpected Answer, 1933] I showed a closed door in a flat in which an odd-shaped hole unveils the night.”9

In comparison to Magritte, some of his compatriots in Surrealism have been studied in more depth by film scholars—namely, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí—because, unlike Magritte, they made experimental or narrative movies that were publicly screened and have become classics (e.g., Un chien andalou [1929], L’âge d’or [1930], The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie [1972]), or they collaborated with mainstream directors (e.g., Dalí with Alfred Hitchcock on Spellbound [1945]). In a certain sense, however, in comparison to Dalí, much of whose art contains an element of abstraction or distortion (and is therefore unlike the unvarnished photographic image), Magritte’s is at least superficially realistic—though the situations he creates are patently unreal. When asked why he employed this style, he responded, “Because my painting has to resemble the world in order to evoke its mystery.”10 In this regard, Magritte falls into what Bruce Elder calls the “veristic” wing of Surrealism versus the “automatist” wing (which “believed that the way to freedom in painting was to break from depiction”). The veristic artists “were interested primarily in the mind’s activity of forming the world that we inhabit.”11

Clearly, Magritte’s work conforms to certain tenets of Surrealism: an interest in a world beyond the quotidian—one informed by mystery, poetry, and enchantment. As André Breton once famously asserted in his 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism, “Existence is elsewhere.”12 As this chapter’s epigraph demonstrates, Magritte put it somewhat differently, speaking instead of liberating revelation.

While many of the Surrealists drew on dreams and the unconscious for their imagery, Magritte generally did not, gleaning his ideas instead from intense concentration. Neither did he depend on chance (also valorized by the Surrealists); rather, his paintings arose from conscious choices. Like most Surrealists, Magritte was also interested in bizarre and often humorous juxtapositions—be it an open umbrella atop of which sits a glass of water (as in Hegel’s Holiday [1958]) or a birdcage that contains an egg rather than an avian creature (as in Elective Affinities [1933]). It is no accident that in both of these cases Magritte utilizes an iconography of objects—also an interest of the Surrealists—though freed of their utility and always in strange contexts. Here we may think of Man Ray’s Cadeau (1921) a sculpture comprising a clothes iron with nails jutting out of its surface. Furthermore, Magritte shares the Surrealists’ interest in playing with language in ways that defy coherence and rationality (as in the Interpretation of Dreams series [e.g., 1927, 1930, 1935], in which pictures and word labels are often mismatched). Here a precedent may have been the Surrealist game of exquisite corpse (begun around 1925) whereby one player would write a phrase on paper, hide most of it with a fold, and pass it on to another player to continue. The result was a collectively authored nonsense composition. While Magritte generally worked alone, he did often farm out the creation of titles for his works to other members of the Belgian Surrealist circle so that the titles would not reveal authorial intent. Finally, the Surrealists (a group composed almost entirely of apparently heterosexual men) were fixated on the female erotic image. Magritte is no exception, although (perhaps in a bourgeois move), the woman he most often painted was his wife, Georgette. As previously noted, while many of the Surrealists worked in abstraction (e.g., the Chilean painter Roberto Matta), Magritte preferred a style superficially faithful to the everyday world.

Here, of course, we recall that until recently, with the advent of computer-generated imagery (CGI), film theory has stressed the verisimilitude of the cinematic image, with André Bazin deeming the latter a “decal” or “transfer” of reality onto celluloid.13 Likewise, Siegfried Kracauer sees film as offering a “redemption of physical reality.”14 So Magritte’s pictorial realism has potential ties to the ontology of the medium. Moreover, as already noted, his art is marked by a focus on objects (balls, tubas, frames, combs, etc.)—often removed from their usual framework. As Magritte has remarked, “Setting objects from reality out of context [gives] the real world from which these objects were borrowed a disturbing poetic sense by a natural exchange.”15

Here again, film theorists have often noted the medium’s ability to concentrate on things instead of people. As Bazin writes in “Theater and Cinema,” “On the screen man is no longer the focus of the drama. . . . The decor that surrounds him is part of the solidity of the world. For this reason, the actor as such can be absent from it, because man in the world enjoys no a priori privilege over . . . things.”16 Again, Kracauer agrees. He sees one of cinema’s special capacities as that of capturing the inanimate (a clock on a mantel or a vase on a table)—parts of material reality that would otherwise go unnoticed in daily life. Significantly, Magritte’s art has been linked to the realm of the “every day.” Finally, the originality of Magritte’s method lies not so much in his painting skill as in the inquiries and conundrums his canvases raise about topics like vision, identity, illusionism, framing, or language versus picture—all matters that are highly relevant to filmmaking practice and theory.

But conceiving the connections between Magritte and cinema is a process that is far less literal than detecting the parallels between Dalí’s Spellbound sequence and his painting style. Magritte’s artistic signature attaches to no such movie, other than his amateur ones (see chapter 2 for further discussion). Moreover, aside from the few cases of acknowledged cinematic tributes to Magritte or documentaries about him, there are no films (to my knowledge) in which images from his canvases are literally transferred to the screen—although there are some in which his paintings themselves appear as part of the decor (one is The Thomas Crown Affair [1999], discussed in chapter 3). Rather, the task of unearthing cinema’s ties to Magritte requires intuitive and imaginative leaps, though ones based on a knowledge of film history and discourse. Of course, such factors are always at play in successful art criticism, but they are rare...