![]()

1

Creating from the Inside Out: A Brief Introduction to the Martha Graham Dance Company

No artist is ever ahead of his time, he is the time. It is the rest of the world that has to do the catching up.

—Martha Graham

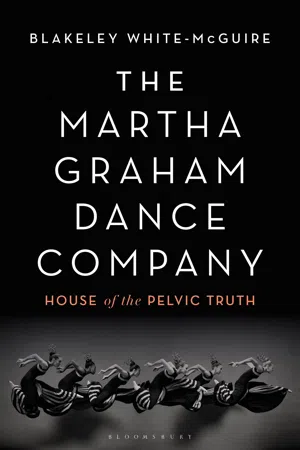

FIGURE 3 Deo by Bobbi Jene Smith and Maxine Doyle. Dancers: Xin Ying, Leslie Andrea Williams, Anne O’Donnell, Anne Souder, Marzia Memoli, Laurel Dalley Smith, and So Young An. Photograph by Christopher Jones.

As a girl, Martha Graham attended a performance given by the legendary dancer Ruth St. Denis. She would later say, “Ms. Ruth opened the door, I walked into a life.”1 At the Denishawn School she had studied quixotic theatricality, costuming, and thematic dances of imagined world cultures which catered to its Euro-American audiences. Although she was his student, Ted Shawn chose Martha to be his dance partner which eventually led to her star turn in the Greenwich Village Follies. There, she performed for New York City’s Vaudeville audiences and began a new stage in her life. The artistic community of New York would have a significant influenced on her artistic expression and lead her into a new realm of dance.

Under the guidance of composer Louis Horst (also from Denishawn), she would find a new direction by moving away from dancing as entertainment and toward its potential as transformative art. Horst became a tremendous influence as both her musical director and friend. He pushed her hard to find new forms through her own body and introduced her to avant-garde artists and vital composers of the day. With Horst she encountered new influences from the modern art period that revealed radical possibilities and helped her to break away from Denishawn-ian concepts of dance.

In founding the Martha Graham Dance Company, Graham formed both physical and metaphysical spaces for her artistic development. Her vision of dance revealed it as not only ritual and expression but also as theater. She presented dance as a dominant form in theatrical presentations instead of as a supporting one. The company gave its first performance in 1926 with Graham and three of her students from the Eastman School of Music, Thelma Biracree, Betty Macdonald and Evelyn Sabin, dancing a program of solos and trios. This foundational relationship between dance teacher and student continues to be vital to the continuity of the Company.

Like many artists in the mid-twentieth century, Graham sought to create an original American art form coming from the ferment of place. Cultural identity and oppression were early themes in her dances such as Heretic (1929), Immigrant (1928), and Imperial Gesture (1935). Although she was a product of her birthplace (Pennsylvania) and childhood home (California), her vision reached beyond borders of nationality. Her dances still move us into a frontier of discovery that reveals our common and complex emotional human nature. In this excerpt from a program titled “Martha Graham and Dance Group Program,”2 she articulated her early perspective:

It [the creation of an American dance form] requires that the choreographer sensitizes himself to his country, that he know its history, its political and geographical life, and that he direct and correlate his experiences into significant compositions of movement.

No great dance can leave a people unmoved. Sometimes the reaction will take the form of a cold antagonism to the truth of what they are seeing –sometimes a full-hearted response. What is necessary is that the dance be as strong as the life that is known in the country. That it be influenced by the prevailing expression of its people as well as by the geography of the land itself.

She made dances with huge themes in a repertory that blended ideas from world cultural practices; Graham did not claim originality. Her artistic manifestations reflected the creative environment in New York City at the time as well as a colonizing practice that was foundational to her native United States culture. She placed theater from Europe, symbolism from Asia, and ritual from North America, one on top of another. She used imagery, styles of dress, and symbolic forms found outside of the familial culture of her childhood. Whether or not she appropriated vocabulary or symbolic language is a significant question. She acknowledged and cited her sources of inspiration and integrated her embodiment of ideas through rigorous study, practice, and development. Graham said “there is nothing new, there is nothing to be discovered, the dance need only be revealed.”3 This acknowledgment of dance as revelation rather than product prompts me to consider her self-awareness of artist as vessel rather than originator. Her revolution came in her presentation, her craft of storytelling and her leadership. Graham placed her dance as the central mode for expression in her theatrical productions rather than as ancillary or responsive one. Her repertoire exposes a devotion to dance and the human body as a vessel for the sacred rituals of human life.

Her Dances

Many artists in the 1930s made work through the lens of citizen and humanist. In Panorama (1935), her choreography for the female students at Bennington College, Graham structured her activist ideas into three sections. Early program notes accessed through the Martha Graham Resources archives state her thematic intentions: Theme of Dedication, Imperial Theme, and Popular Theme. The choreographic structure of the dance presents large groups of people moving in athletic rhythmic formations. Its actions call to mind the activism that is necessary to bring about any significant change in minds and lives of people. She writes “this theme is of the people and their awakening social consciousness in the contemporary scene.”4 The pedestrian movements of Panorama are accessible to untrained movers and named for basic forms of physicality such as unison lunge switches, kneeling, walks, prances, and arm beats. Its reconstruction in the early 1990s led by the luminary dancer Yuriko, and its subsequent re-staging within the Graham community of dancers has led to its now yearly performance in the All-City Panorama. In this special New York City event, high school students from the five boroughs audition and are then invited to learn and perform Panorama in the Martha Graham Dance Company’s New York performance season. New generations are embodying not only the work of art, but they are also learning about the dance his(her)story of artists in their city. The life of this work demonstrates how transference of accumulated knowledge circulates back into its community of origin with renewed vitality and resonance.

Looking at transference through the metaphoric lens of writing, dance scholar and political philosopher Dana Mills describes this phenomenon in her book Dance and Politics: Moving Beyond Boundaries. She introduces the sic-sensuous act “of writing one’s body upon another body, and bodies writing upon their space” (16). Mills states:

Dancer’s bodies are also the pens with which they write on others bodies. Reading dance as a language and a way of knowing means that the body is both the instrument of writing and the surface upon which it writes […] I argue that the strong reading of political dance is intimately intertwined with the understanding of dance as an embodied language, a method of inscription independent of words […] sic-sensuous [is] a concept which I utilise in order to focus upon acts of writing performed by manifold bodies who have written upon the argument; the argument in turn turns the spotlight on moments of shared sensation.

(15)

Mills’ concept of sic-sensuous addresses both individual and communal cultural practices by examining how a dance work moves over time through one body to penetrate the body and psyche of another.

Scholar and former Graham dancer Ellen Graff describes in her book, Stepping Left, the conditions of the historical period when dance artists such as Graham were making dances with revolution in mind. Graff writes:

What established their credentials as revolutionary artists was the content of the dances, the political and social commentary that emanated from the percussive thrust of a heel or a head’s abrupt turn. Radical dancers may have openly embraced bourgeois technique, but they did not dance about “the life of a bee.” They danced about the lives and concerns of working people.

“The Worker” however was increasingly absent from the stage. In the most artistically successful efforts by revolutionary dancers, the worker was an imagined inhabitant of a trained body rather than a participant in the experience … What established their art as revolutionary was content; in essence, their dances were narratives about crises affecting the worker.

(75)

Frontier (1935) is a joyous dance of a young girl indulging her dreams and exploring her desires to answer the call to adventure. It embodies an attitude I will, I can, yes. Movements in this minimalist work develop as simple variations on a theme. Graham mined the universal emotional experiences of joy, excitement, and desire in her work. While there is nothing ordinary about the dances of Martha Graham, many of her early themes did speak to the everyday inner life of people. The frontier, whether in space or imagination, is another theme in her dances. The landscape and imagined possibilities are synthesized through her outbursts of high kicks, jumps, small skitters and pumping heel lifts. In the dance, the beauty of the landscape brings the girl to her knees.

The gestures are intensified by the simplicity of Isamu Noguchi’s set designs and the resolute snare drum beat of Louis Horst’s musical composition. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–88) built many of the environments for Graham’s dances including Frontier and Appalachian Spring (1944). Noguchi’s stage setting for Frontier is a simple free-standing link of log fence and a cotton rope. The rope shapes the space stretching out in a V from the upstage center of the floor seemingly into infinity. Noguchi said “I used a rope, nothing else, it is not the rope that is the sculpture, but it is the space which it creates that is the sculpture. It is an illusion of space” (“Tribute to Martha Graham”).

Space is another reoccurring thematic idea for Graham. In her autobiography she described significant influences on her (some relating to space) including the particularly molding experience of moving across North America by train from Pennsylvania to California. It was a life-altering journey out of the settled East of North America into the West. She describes feeling the wildness of the landscape in her imagination and in her body.

The train was taking us from our past, through the vehicle of the present, to our future. Tracks in front of me, how they gleamed whether we went straight ahead or through a newly carved-out mountain. It was these tracks that hugged the land, and became a living part of my memory. Parallel lines whose meaning was inexhaustible, whose purpose was infinite. This was for me the beginning of my ballet Frontier.5

The individual self in relationship to the landscape is at the heart of Frontier; its ethos is simply human. The girl in Frontier is a settler. Graham amplifies her emotional experience, her boldness, and her quickening of spirit. Her gestures are set against a backdrop of intentional, systematic erasure of Indigenous people’s histories by settlers. The genesis of the United States of America as a nation of settlers seeking to claim land and dominate Indigenous cultures is inherent in much of US-American art; is an existential reality of the art itself. This history is unseen yet expressed in the feeling and sound of discord that wafts in and out of Frontier. The dancer is answering the call to explore the unknown and all that that adventure conjures. Much like Thoreau, Graham relates the untamed wildness of North America with an inner awakening. Author Dana Mills concurs, “Just as the Founding Fathers sought to establish both a new political system and landscape, so artists sought to build a cultural life appropriate for such a new republic” (56). “ Two stages need to be distinguished: the perception of the landscape by the artist and the subsequent perception of the [art] by the view” (63).

In Appalachian Spring, Graham uses symbolism in costuming from the pioneering period as well as Noguchi’s skeleton-like structure of a town to indicate time, form, and temporality. This dance tells the story of towns ...