Subsistence Businesses, Economic Survival or Economic Success Stories?

In an ‘Idols’ audition snippet which went viral in the township a few years ago, Gareth Cliff asks a contestant what he does for a living.

‘I sell things,’ he answers.

‘Like what?’ asks Gareth.

‘Cigarettes, airtime, sweets and things!’

‘Oh, so you are a vendor?’

‘No!’ is the indignant answer.

‘Oh, so what are you?’ asks Gareth.

‘I’m a Zulu!’

In the KasiNomic Revolution there are the small guys in the streets, the foot soldiers of this revolution, carrying on every day in the dust, the dirt, the dusk and the dawn. They are the multitudes, some earning relatively large amounts of money, some surviving, most making a good living and supporting themselves and their families.

These foot soldiers are regulated, restricted and hobbled by municipal regulations, by lack of access to resources or funds, sometimes restricted by their own evaluation of themselves and the potential of their businesses.

Yet they survive and excel. They are the insurgent guerrillas in a formal world, a force rising in influence and extent. These kasi businesses are the future, the untapped potential of entrepreneurship and micro business.

Here are the unsung heroes of the KasiNomic Revolution …

THE KASI SCHOOL TUCK SHOP

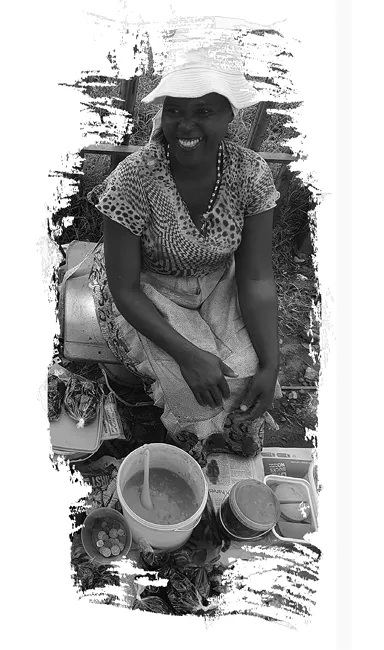

Sizakele is a Swazi. I can hear it in her lisping ‘t’ which Swazis use instead of ‘z’ in what is in effect Zulu. She is a pretty vivacious woman seated comfortably on a crate, a white spotti, the floppy hat of ekasi, shading her sparkling eyes, and as she chats she unpacks her goods from an old Pick n Pay trolley she uses as her transport.

Sizakele arranges her goods in an expert manner on a low wooden plank placed on two cement blocks, some plastic red roses (it’s nearly Valentine’s Day), a pile of pencil sharpeners and short rulers, erasers, cheap BIC pens, some pencils and little pink Mickey Mouse glue sticks. Next to these she neatly arranges her main lines, old margarine and ice cream containers filled with slices of bright pink fried polony, another bowl of green mango atchar in red oil, a pile of fried Viennas cut in half, some red-brown greasy Russians curled up from frying. In little knotted plastic bags she has fried potato chips with polony and Russian bits. Probably the detritus of the whole fried ones, looking soggy and yucky to me, but no doubt delicious and greasy and filling to the multitude of school kids about to descend on her perch.

A larger pile of knotted plastic bags are full of a goo-like black substance which she laughingly tells me is sweet and I should try it, watching my face as I grimace at the thought. Complementing all the savoury snacks are piles of shwam shwams, kiep kieps and siqedas – orange chips that go shwam shwam in your mouth, popcorn named after chickens which go kiep kiep, and frozen ice popsicles which finish your thirst hence the word isiqeda, finished. Next to her is a large bread crate with white bread slices neatly placed in threes, fours and sixes in clear plastic envelopes. As the kids pour out of the classroom and surround her like a sea of white topped egrets they say three, four or six and she grabs the appropriate number of slices in their bag and pours a large spoonful of soup over the slices, followed by a teaspoon of atchar and then a Vienna, Russian or polony slice goes in and she hands over the sloppy goo to an eager hand getting R2, R4 or R5 in return. She must sell about 50 bags in 15 minutes to the multitude of hands which stretch out to her, coins held ready to exchange for slop.

A little seven-year-old girl buys a plastic red rose and a bag of kiep kieps. ‘Who is the rose for?’ I ask her in Zulu. She smiles shyly, looking at the ground and not at me, as a child should when addressing an adult, clutching the rose to her chest as if I want to steal it from her. ‘It’s for Valentine’s Day,’ she whispers, and I’m left in the dark who gets this pretty Valentine’s gift as she hops off with a bunch of girls excitedly saying, ‘The mlungu speaks Zulu, he asked me who the flower was for!’

Around me are 20 other women all like Sizakele, selling a range of almost identical meals, although some sell little kotas, a quarter loaf of bread with the inside gouged out and ‘slap’ chips, polony slice and atchar on top; others focus more on sweet stuff, lollipops, bubblegum, sweet biscuits repacked in three, four or six biscuit bags. The offerings are an assortment of high-end branded items like Stumbo Pops, Smoothies, NikNaks or cheap and nasty fong kong versions of the same, but cheaper ‘for those who can’t afford’. Each woman is surrounded by about 20 to 50 kids all spending R2, R5, some even R10 for their snacks and meals. Another queue of kids, the poorer ones without ikeri, the word for pocket money, literally meaning ‘carry money’, line up with empty bowls or Tupperwares for the feeding scheme food. Huge pots of rice, fried cabbage and soya mince are perched on school desks where local volunteer moms dish out large helpings into each outstretched bowl or Tupperware.

This is break time kasi style. The schoolyard mamas, as they are called, are a feature at every school. They are registered with the school and pay the school R2 a day for their little space on a crate or an upturned brick at school breaks and after school. At some schools they must sell from outside the fence which they perch against, serving their wares through a soccer ball size hole made in the fence for that very purpose. These are the tuck shops of the kasi schools, and a part of school life for generations of school children.

As the rush subsides and the kids all walk off with their meals and their snacks and their sweets and gather in little groups on the cement school sidewalk, or under sparse clumps of shade in the dusty school grounds, chattering happily away while they share their meals with one another, I casually ask Sizakele how long she has sold here. She hesitates while she does a mental calculation using her fingers, her brow furrowed for a moment.

‘Twenty-six years,’ she says casually.

‘Twenty-six YEARS!’ I gasp. ‘Every day five days a week for 26 years?’

‘Yes,’ she says, ‘since 1992, every school day since then.’

‘Why?’ I ask.

‘No one works in my family so I do, and I have put two of my children into university,’ she says proudly. ‘Although in second year both dropped out,’ she adds, looking down and clearly upset. ‘And my husband is at home, he can’t find work, so I am the one who must feed and look after them. Now my children are looking for work but they can’t find work.’

‘Why do your children not work here with you?’ I ask, knowing the answer.

‘Hawu, HERE, ayibo,’ she exclaims. ‘They want a real job, they would not do this.’

‘But you put them in university from this job, you feed them from this job, how can this not be a real job?’ I ask, a teasing tone in my voice, softening what I know is a difficult question.

She smiles ruefully. ‘Yes, it’s a real job for me, but not for them, for this is not a job for educated people!’

Sizakele sells R500 to R850 worth of her goods per day, five days a week. In the last and first weeks of the month she makes the higher amount; parents who don’t give their kids ikeri during the month do in the first week of the month. Of this she carefully counts out and puts aside money to ‘stoka’ at the wholesaler.

‘How much do you put aside?’ I ask. ‘How do you know that it’s enough to restock?’

She looks at me askance, her eyes twinkle and she says teasingly, ‘Mlungu, I have been doing this for 26 years, I can look at this table after break and I can tell you how much I have sold in a few seconds. It’s not only you educated people who know business!’

I feel like a schoolboy asking stupid questions; she’s right, I would not ask a supermarket owner with 26 years’ experience how they know their business!

‘Every day I keep my profit aside from my money for stocking. Some days it’s R350, some days it’s R500. This is my money to live.’

There are about 200 school days in the South African school year, that’s R70 000 to R100 000 a year or around R6 000 a month. That’s a reasonable income, if you consider a domestic servant is lucky to earn R3 000 a month working eight hours a day, five days a week. Sizakele works at the school for three hours a day, excluding her preparation time at home. If the other 19 ladies at the school make anything like her, then this school generates R100 000 a month in income for 20 families. There are 24 543 government schools in South Africa, granted not all kasi schools, but even if we worked on 12 000-odd schools in the townships, this is employment and an income for 200 000 women earning around R3 000 to R6 000 a month!

So Sizakele is officially unemployed, she does not have a real job according to her kids and formal society, she gets no help from anyone; she is not interested in another formal job, she loves hers and the kids, yet she is called a survivalist business or a subsistence worker, effectively meaning hand to mouth, living on the edge. But is she? No, definitely not, she and 200 000 school mamas like her around the country are businesswomen, worthy of respect and admiration and it’s time to recognise they have real jobs.