![]()

1

Introduction

In American agriculture at the beginning of the twentieth century, optimism prevailed. A long period of low prices and low farm incomes had ended in 1897, and the subsequent income improvements had been sustained. In its economic review of 1899 the New York Times reported: “The farmer, the miller, the stockman, and all classes engaged in like industries are reaping the benefits that flow from bounteous harvests and good prices” (January 1, 1900, p. 2). The secretary of the National Live Stock (it was two words then) Association expressed an ebullient confidence seldom heard from farmers before or since: “The live stock industry of the United States was never in a more prosperous condition than it is at the present time. The live stock men of the country can ask for no greater blessing than a continuation of these conditions. That they will do so for a number of years there seems to be little or no doubt” (ibid., p. 13).

And the optimists were right. Eight years later, in the 1908 Annual Report of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agriculture Secretary James Wilson said in his twelve-year review, “This period has developed an amazing and unexampled prosperity for the farmer . . . With better houses filled with modern conveniences, the family life has developed in strength and in enjoyable living . . . the farmer’s labor is rapidly becoming less in physical stress, and the burdens are becoming lighter . . . The farmers of the mortgage-ridden state of Kansas of former days have stuffed the banks of that State full of money” (USDA 1908, pp. 151–152).

Broad credence in this rosy view is evident in marketplace indicators: rising farmland prices and increasing farm numbers. Economic conditions improved still further after 1910, with the period 1910–1914 being labeled the “golden age of agriculture” and cited for the following half century as an economic ideal to be sought after through government policies.

Yet after World War I farm prosperity evaporated with remarkable speed and stunning persistence, culminating in 1929–1931. The farm economy has had profitable periods since, but has never regained the sustained optimistic tone of the first fifth of the century. Nor has farming ever fully regained the significance it had at that time in the national economy. Since 1920 the United States has lost two-thirds of its farms and, in the course of that decline, helped to populate many urban neighborhoods with its refugees. Nonetheless, the farms that remained in 2000 had attained a level of income and wealth far beyond any seen in the “golden age,” both absolutely and relative to the nonfarm population.

One purpose of this book is to assess the good news and the bad news in the story of the U.S. agricultural economy. The two sides of the story are connected, in that the decline of farm numbers reflects an astounding increase in farmers’ productivity. With one-third the labor force committed to agricultural production as was the case in 1900, America now produces seven times the farm output. Crop yields per acre have increased phenomenally, as have milk yield per cow and other indicators of animal productivity. The real prices that consumers have to pay for farm products have fallen by half. As late as 1950, food consumed at home accounted for 22 percent of the average U.S. household’s disposable income. By 1998 that percentage had been reduced to 7.1 During this same period, the average farm family’s income had risen from below to above that of nonfarm families.

One may nonetheless reasonably question the conclusion of twentieth-century American agricultural success. We cannot forget the economic losers, the millions who have had to live in grinding rural poverty and those who left farming because of economic pressure, often extending to bankruptcy. The biggest decline was among African American farmers in the South, where almost a million such farms prior to the Depression have been reduced to about 20,000 today. Many of the more isolated rural communities have seen their population base severely depleted and have become economic backwaters, with small towns virtually abandoned. Moreover, U.S. agriculture as a whole has had to weather general economic instability and sustained periods of economic crisis in the 1920s, 1930s, 1950s, and 1980s. Those who remain in commercial agriculture are under market-driven pressures that make some of the traditional attractions of farming as a vocation economically unfeasible. This after the expenditure of hundreds of billions of federal taxpayer dollars in support of agriculture. To top it off we have consumers who believe today’s manufactured food products are pale imitations of genuine articles of the past, while today’s commercial farms are thought by many to present greater threats to the environment than the smaller farms of earlier decades.

Despite these and other problems, the development of U.S. agriculture in the twentieth century is on balance a great success story. A detailed consideration of the evidence for and against this conclusion is one purpose of this book. But more basic is the question of how and why American agriculture evolved as it did after 1900. An attempt to answer that question is my second and more complicated purpose.

Some readers may question the twentieth-century focus of the book. Perhaps the features of U.S. agriculture that make it a marvel of technological progress and productivity were already in place in 1900. Isn’t the real question how we got to that stage? Unfortunately, pushing back our analytical starting point to 1840, say, when we first have somewhat reliable detailed data to work with on a national scale, would not solve the problem. U.S. agriculture may well owe much to its favorable position going back to colonial days and the early Republic; but no one book could hope to cover all of the relevant history in sufficient detail even if the data were less sketchy than they are. More directly pertinent, there was an acceleration of U.S. agricultural development during the twentieth century that appears unlikely to owe much to nineteenth-century foundations. Analysis of that acceleration is an important aim of Chapter 2.

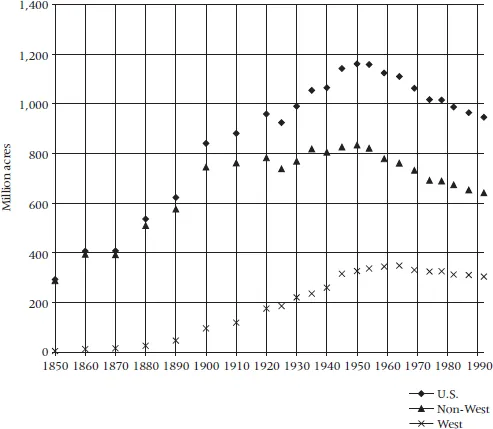

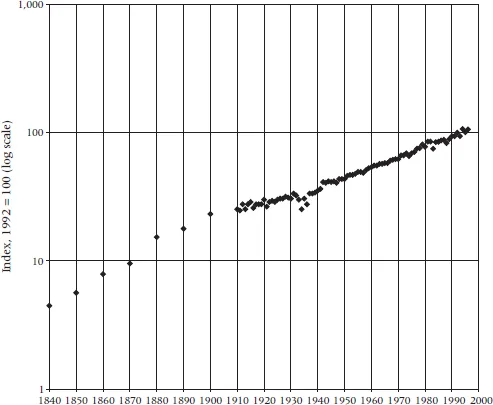

Moreover, the twentieth century is different from what went on before in that 1900 roughly marks the end of the period of geographical expansion of U.S. agriculture. Frederick Jackson Turner placed the “closing of the American frontier” at 1890, but for agriculture this is too early. U.S. agriculture was growing rapidly at its extensive margins all through the 1890s. U.S. land in farms increased by more than 200 million acres (25 percent) in this decade, the largest increase in any decade of our history. The growth of land in farms was slower after 1900, with the exception of the West (Figure 1.1). The shift away from land-based growth of agriculture as new territory opened up is apparent in the slower growth rates of U.S. farm output after 1900, as shown in Figure 1.2.

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 introduce technical data problems that recur throughout the book. First, in order to compare growth rates over long periods of time, logarithmic scaling of the data is preferable to plotting the data themselves. Second, consistently defined statistical measures are typically available for stretches of several decades at best, not the whole century. Long-term comparisons have to be patched together by linking data from several sources. Third, “farm output” is not a straightforward concept; it combines disparate products (indeed it is a paradigm case of adding apples and oranges), some of which have changed in nature over time. We will revisit and assess these problem areas in the next chapter.

Figure 1.1 U.S. land in farms. Data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Census of Agriculture.

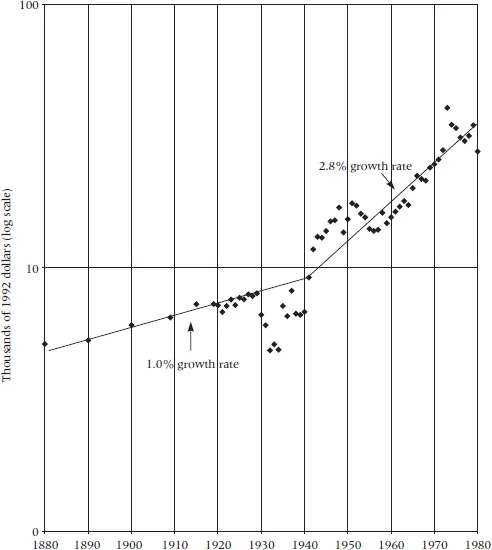

A striking turning point in U.S. agriculture is illustrated in Figure 1.3, which shows U.S. real agricultural gross domestic product (GDP) per person in farming (farmers and hired farmworkers) for the hundred-year period 1880 to 1980.2 Agricultural GDP per person is analogous to the per capita measures that are the standard indicator of economic growth. For the sixty years between 1880 and 1940, excluding the Depression of the 1930s, the trend rate of growth is 1.0 percent per year. This is a respectable growth rate and generates a doubling of real incomes in seventy years. (The sketchy data available indicate essentially the same rate of growth from 1840 to 1880; see Towne and Rasmussen 1960.) After 1940, excluding the years of World War II, the trend rate of growth is 2.8 percent annually.

Figure 1.2 U.S. farm output, 1840–1996. Data from U.S. Department of Commerce (1975); extended to 1996 using U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Statistics.

What accounts for this tripling in what had been a fairly stable if unexciting long-term trend? Before attempting to address this question, which is at the analytical core of this book, we need to be clear about the facts of twentieth-century agricultural history in as precise a way as possible. Has the advance of productivity been a steady climb or are there specific episodes of growth, and if so can they be attributed to specific causes? How good are our measurements of output and input growth, and of the sources of this growth? How large were the costs of achieving it? What has been the economic fate of those who left agriculture and those who remained behind? How can we properly measure the economic and social status of households in today’s rural communities as compared with those of former days?

In addition, there are questions about who reaped the rewards from productivity growth in U.S. agriculture: farmers or agribusinesses who sell inputs to farmers and buy their products? Large- or small-scale farmers? Landowners or farmworkers? To what extent have food consumers shared in the gains? Have we sacrificed too much in soil erosion, wildlife habitat, bucolic landscape, water-quality degradation from chemicals?

Figure 1.3 One hundred years of U.S. real farm GDP per person in agriculture. Data from U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Outlook, various issues, and U.S. Department of Commerce, Survey of Current Business, various issues, for data since 1929; Towne and Rasmussen (1960) for data before 1929.

Many of these questions point in the direction of political action. Proposals for public policy remedies have pervaded discussion of problems of U.S. agriculture. Here too, it is important to look first at facts and history. What have been the consequences of our agricultural and rural policies, especially the over sixty-five years of intense experimentation with farm programs initiated with the New Deal of the 1930s? In considering how U.S. policies might have been better directed, and how they might best be formulated for the future, it is important to understand how the market/policy nexus has developed. Who have been the gainers and losers from these policies?

Although answering these questions is important for understanding our country’s history and prospects, it is perhaps even more important to have an accurate assessment of lessons learned because many nations of the world now face situations in which agricultural productivity growth and farm-sector economic adjustment remain to be achieved. The U.S. experience may provide lessons useful in the policy debate in these countries.

My approach in this book is to begin with a detailed analysis of the facts and data available on changes in agricultural technology (Chapter 2), the economic situation of farm enterprises and of the farm population (Chapter 3), out-migration from agriculture, rural poverty, and rural communities (Chapter 4), the functioning of agricultural commodity and input markets (Chapter 5), and governmental action influencing agriculture (Chapters 6 and 7). I then turn to explanations in Chapter 8. This discussion leads to further examination of data that reinforce the belief, already evident in the earlier chapters, that U.S. aggregate data are insufficient to resolve many of the key questions. In order to place a greater range of historical data in our purview, Chapter 9 takes up a systematic exploratory econometric investigation of state-to-state differences in the economic development of agriculture. The hypotheses that appear most likely to be illuminating after this work are then tested on still less aggregated data, for a sample of 315 U.S. counties, in Chapter 10. In Chapter 11, I pull together what has been learned and examine the implications.

![]()

2

Technology

American agriculture has been transformed in the past hundred years by changes in the technology of farming. Farms as economic enterprises have also changed, along with the roles of farm owners and workers. Farms are generally larger and more specialized, and for some commodities the traditional farm is on the verge of disappearing. These changes are closely related to changes in technology.

Technology can be defined in an abstract sense as the set of possible outputs that can be obtained from given inputs of land, labor, and capital. Technology in a concrete sense is what the inputs do or have don...