Chapter 1

The Sun Also Rises

I

Spain in 1936 was a land not well known to many foreigners. W.H. Auden memorably described it as ‘that arid square, that fragment nipped off from hot Africa, soldered so crudely to inventive Europe’. To George Orwell, writing of how he pictured Spain before he first travelled there, it was a land of white sierras and Moorish palaces, of goatherds and olive trees and lemon groves; of gypsies and girls in black mantillas, bullfights, cardinals and the half-forgotten terrors of the Inquisition. Of all Europe, he would write in 1937, Spain was the one country that had the most hold upon his imagination.

But Spain was not simply a land of the imagination. In the years immediately around the Great War a number of British and American writer and artists travelled – even settled – there. Their books and paintings added layers of modernity to Orwell’s almost oriental vision. Yet they, too, sometimes mirrored his exotic impression. For Spain was a land not quite like anywhere else in Western Europe.

The American novelist John Dos Passos first visited Spain in 1916, a few months after graduating from Harvard. He had travelled already in France, Italy and Greece, yet wrote that nowhere else in Europe had he so felt ‘the strata of civilization – Celt-Iberians, Romans, Moors and French have each passed through Spain and left something there – alive … It’s the most wonderful jumble – the peaceful Roman world; the sadness of the Semitic nations, their mysticism; the grace – a little provincialized, a little barbarized – of a Greek colony; the sensuous dream of Moorish Spain; and little yellow trains and American automobiles and German locomotives – all in a tangle together!’ When the author Lytton Strachey visited Granada in the spring of 1920 he too was captivated: ‘Never have I seen a country on so vast a scale,’ he wrote home, ‘wild, violent, spectacular – enormous mountains, desperate chasms, endless distances – colours everywhere of deep orange and brilliant green – a wonderful place, but easier to get to with a finger on the map than in reality!’

Strachey’s travelling companion, the artist Dora Carrington, would be equally moved, capturing the landscape and its people in scintillating oil colours. She would be one of the first in a long line of post-war British artists to visit Spain: Ben and William Nicholson, Augustus John, David Bomberg, Mark Gertler, Henry Moore, Edward Burra, to name only the most well-known. And there were English-speaking writers, too, making of Spain a place to wander: Ralph Bates, Waldo Frank, Robert Graves, Ernest Hemingway, Laurie Lee, Malcolm Lowry, V.S. Pritchett, as well as Dos Passos. According to one contemporary literary critic, what had initially attracted Dos Passos (and no doubt some of the others, too) was the discovery in Spain of ‘an attitude toward life and a way of living which are in pleasant contrast to the mad turmoil of industrial Europe and America’. Nonetheless, in his 1917 essay ‘Young Spain’, Dos Passos observed a country – with its corrupt, inefficient politicians and its ill-educated, underpaid workforce – ripe for revolution. It was only, Dos Passos considered, a sort of despairing inaction that prevented it.

Insight into the country’s deeper complexities often came only with time. Strachey and Carrington’s host in Spain, the writer and Great War veteran Gerald Brenan, admitted that when he had chosen to settle there the previous year he had known next to nothing about the country. In due course, and over many decades, he wrote a series of books that would bring Spain – its language, its culture, its politics – to life for many English-speaking readers. Ernest Hemingway would call Brenan’s 1943 study, The Spanish Labyrinth, a ‘splendid book’, ‘the best book I know on Spain politically’.

Hemingway was the writer who really captured for a broader audience the foreigner’s experience of Spain in the decade following the Great War. Born in Chicago in 1899, the son of a prosperous doctor, Hemingway passed a seemingly idyllic childhood, enjoying sports and writing at school and long summers hunting and fishing with family and friends. Having launched on a career as a journalist with The Kansas City Star, early in 1918 he decided to head for Europe and the Great War, volunteering with the Red Cross. He served (like John Dos Passos) as an ambulance driver in Italy, where he was seriously wounded by a mortar burst and machine-gun fire. This – and the doomed romance with an American nurse that followed – would prove life-defining experiences.

It was on his way home to a hero’s welcome that Hemingway made his first, short stop in Spain. Having married and settled in Paris as a journalist for the Toronto Star Weekly, in 1923 he made two longer trips. Seeking the truth and courage and conviction in human experience that Hemingway believed existed only in the face of imminent death, he was almost immediately transfixed by the corrida de toros. Before his first visit, he thought bullfights ‘would be simple and barbarous and cruel and that I would not like them’; but he also hoped that he would witness in them the ‘certain definite action which would give me the feeling of life and death’ that he was looking to describe in his fiction.

In July at Pamplona Hemingway and his wife Hadley attended the San Fermín fiesta: ‘five days of bull fighting dancing all day and all night,’ he told a friend, ‘wonderful music – drums, reed pipes, fifes … all the men in blue shirts and red handkerchiefs circling lifting floating dance. We the only foreigners at the damn fair.’

‘It isn’t just brutal,’ he wrote of the corrida. ‘It’s a great tragedy – and the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen and takes more guts and skill and guts again than anything possibly could. It’s just like having a ringside seat at the war with nothing going to happen to you. I’ve seen 20 of them.’ To use the Spanish word for a devotee of bullfighting, Hemingway was already an aficionado.

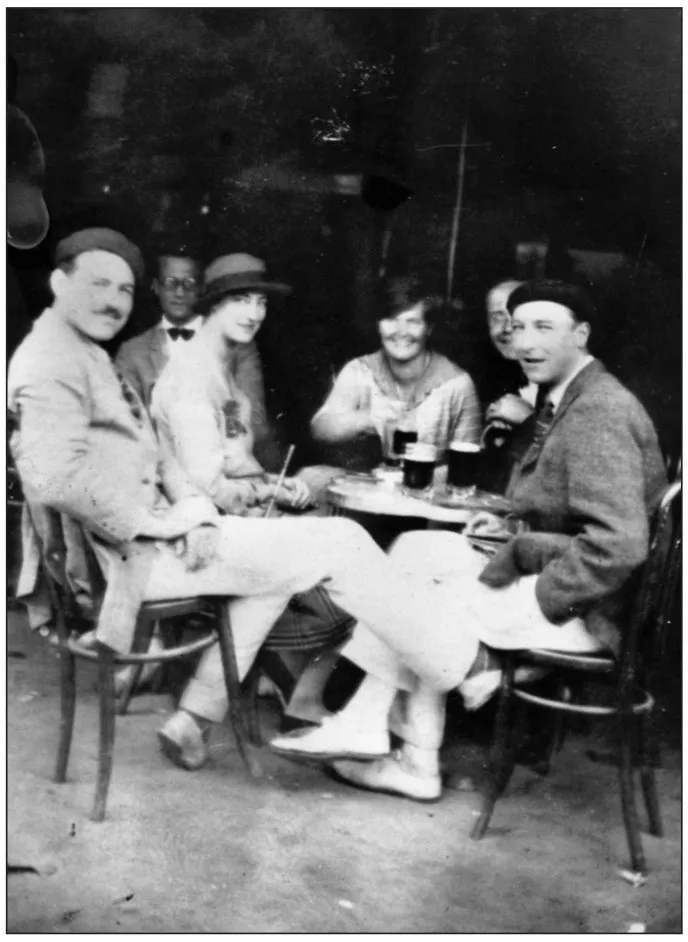

The couple returned the following year with a group of friends, including Dos Passos. After the fiesta they explored the Basque country and the foothills of the Pyrenees, where they hiked and fished. Hemingway had travelled extensively in Europe, and like Dos Passos felt that Spain was ‘the only country left that hasn’t been shot to pieces … Spain is the real old stuff.’

It was a visit to Pamplona in 1925 that provided Hemingway with the material for his breakthrough book, The Sun Also Rises. Published when he was still only in his mid-twenties, the novel told the story of a handful of British and American tourists who (according to one reviewer) ‘belong to the curious and sad little world of disillusioned and aimless expatriates who make what home they can in the cafés of Paris.’ Closely based on Hemingway’s unrequited love for a beautiful Englishwoman, Duff (Lady) Twysden, its finest passages related with brusque relish the Pamplona bullfights. As Dorothy Parker observed in The New Yorker, almost as soon as The Sun Also Rises was published its author ‘was praised, adored, analyzed, best-sold, argued about, and banned in Boston … and some, they of the cool, tall foreheads, called it the greatest American novel … I was never so sick of a book in my life.’ Hemingway’s sparse prose and gritty, realistic dialogue would quickly spawn dozens of less gifted imitators.

However, The Sun Also Rises said more about Hemingway, bullfighting, fishing, drinking, loving and the post-war malaise than it did about Spain. Its epigraph was a truncated version of a remark Gertrude Stein had once made to Hemingway: ‘That’s what you all are,’ she had told him. ‘All of you young people who served in the war. You are a lost generation.’ The effects and after-effects of the Great War permeated the book: one approving American reviewer – the critic Edmund Wilson – considered ‘the barbarity of the world since the War’ to be its very theme: a theme that was then still consuming Western culture. ‘What gives the book its profound unity and its disquieting effectiveness,’ Wilson suggested, ‘is the intimate relation established between the Spanish fiesta with its processions, its revelry and its bull-fighting and the atrocious behavior of the group of Americans and English who have come down from Paris to enjoy it.’

Hemingway’s novel – like his letters and short stories – had almost nothing to say about Spanish politics. Yet in September 1923, only a couple of months after Hemingway’s first extended visit to Spain, General Miguel Primo de Rivera had led a coup d’état that established him as dictator. Perhaps this was unremarkable to Hemingway because coups, revolutions and revolts had become relatively common events in recent Spanish history. Since the extraordinary heights of imperial power and wealth it had enjoyed in the seventeenth century, the country’s standing had steadily declined. After the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte occupied the peninsula in 1808 they left behind a country economically ruined and politically divided.

By 1898 Spain had lost those New World colonies that had once brought its ruling classes great wealth. With the Philippines, Mexico and Cuba gone, the acquisition of northern Morocco as a colony in 1904 was nothing but an expensive, troublesome burden. Compared to the rest of Western Europe, early twentieth-century Spain was a poor and (with the exception of Catalonia) under-industrialized backwater. Two-thirds of its twenty million or so population lived and worked in the countryside, with large tracts of land owned by a tiny minority of the population. Productivity was low, mass education minimal, and in many regions of the rural south poverty was endemic. The Church appeared to take little interest in the plight of the poor, perpetuating a status quo that had lasted centuries, an attitude which resulted in widespread resentment of the clergy. This was a land of stark contrasts. ‘You can’t be in Spain more than half an hour,’ wrote one English visitor in 1936, ‘without becoming painfully aware of the extremes of feudalism that still linger on side by side with the growth of modern capitalism.’

The political situation was no happier. The 1830s had seen a seven-year civil war, and the Republic declared in 1873 was short-lived. Foreign monarchs were invited to intervene, and attempts at introducing land reform, and loosening the grip of the Church and Army, made little progress. Despite the introduction of universal male suffrage in 1890, government was characterized by factionalism, corruption and rigged elections. In Barcelona in 1899 only ten per cent of the electorate bothered to vote. ‘Wretched Castile,’ wrote the poet Antonio Machado, a member of a turn-of-the century group of intellectuals and liberals who sought a way to redeem Spain, ‘once supreme, now forlorn, wrapping herself in rags, closes her mind in scorn.’

More powerful than the new Republican movement – more powerful, perhaps, than the upsurge in regional nationalism – was anarchism. Drawing on the ideas of the Russian revolutionary and philosopher Mikhail Bakunin, Spanish anarchists rejected all forms of government: instead, free individuals would manage their own affairs through consensus and co-operation. Anarchists promised their followers freedom, social justice, land reform and the total destruction of the capitalist system, ideals that caught the imagination of Andalusia’s largely illiterate, landless peasantry and Catalonia’s exploited factory workers. Tens of thousands of Spaniards joined this visionary, idealistic movement, and as the Spanish anarchist Juan García Oliver would tell the English author Cyril Connolly in 1937: ‘If I had to sum up Anarchism in a phrase I would say it was the ideal of eliminating the beast in man.’ In response to the charge of anarchist violence, Oliver replied: ‘Anarchism has been violent in Spain because oppression has been violent.’

And violent it certainly was, for anarchists believed in direct action. A bomb dropped into the audience of Barcelona’s Liceu Opera House in 1893 killed twenty-two people, and by 1921 Spanish anarchists had assassinated three prime ministers. Repression followed, and violence exploded periodically into chaos and devastation. The Church – which owned much of the land and along with the Army shouldered the State’s authority – was a frequent target of public anger. During Barcelona’s ‘Tragic Week’ of July 1909 an orgy of anticlericalism saw 42 churches and convents attacked. Soldiers crushed the uprising with considerable bloodshed.

Barcelona, the so-called ‘city of bombs,’ was the epicentre of Spanish anarchism. A large proportion of the million inhabitants of the ‘Manchester of the Mediterranean’ worked in the textile factories that, through the city’s busy port and railway network, supplied Spain, Cuba and South America with cloth. In 1926 an American tourist described the outskirts of Barcelona as ‘a rampart of warehouses, machine shops, flour, cotton and textile mills, dyeworks, chemical factories’. By contrast, its broad, tree-lined boulevards and wide, residential streets reminded many a visitor of Paris. When the Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky passed through Barcelona in 1916 he noted in his diary: ‘Big Spanish-French kind of city. Like Nice in a hell of factories. Smoke and flames on the one hand, flowers and fruit on the other.’

Barcelona considered itself different from the rest of Spain; it was more industrialized and modernized, the people spoke Catalan, they were wealthier, and thought themselves more cosmopolitan, more European. There was a flourishing artistic scene: Pablo Picasso, Antoni Gaudí, Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí were all either natives or residents of Catalonia. Distant Castile, and its government in Madrid, was regarded with caution, and sometimes fear. As in the Basque region of northern Spain, there was a burgeoning independence movement.

When the horror of the Great War rolled across Europe in 1914 Spain remained neutral. For a while, the country’s economy thrived on supplying the Allies with minerals and industrial goods. But there was also rampant inflation, and affiliation to workers’ organizations soared. Membership of the anarchist trade union, the CNT, ballooned fifty-fold. Inspired by the Bolshevik revolutionaries who had helped overthrow the Russian Tsar in 1917, anarchists and socialists in Spain attempted to foment an armed rebellion. Even liberal elements in Catalonia began demanding home rule, the first step on what traditionalists feared would be the road to independence and the break-up of their country.

It was in Barcelona in 1923 that General de Rivera staged his ‘proclamation’. King Alfonso XIII appointed him head of a military directorate, charged with restoring order, stability and unity. The General curbed press freedom, outlawed strikes and restricted political activity, but he also encouraged capital investment, and there was a period of economic growth.

There was plenty of drama for a novel in these political upheavals. But it was not a story Hemingway chose to tell. His next book on Spain, Death in the Afternoon, was an idiosyncratic guide to bullfighting. Published in 1932, after he had witnessed the deaths of over a thousand bulls in the corrida, its one reference to Primo de Rivera was to remark that under the dictator a more humane measure had been introduced into the ring. Padding would now protect the picadors’ horses from goring by the bulls’ horns. Though Hemingway admitted that the frequent death of the horses was one of its most sickening aspects, he considered the move ‘the first step toward the suppression of the bullfight’.

II

Even dictators fall. By 1930 General Primo de Rivera had become unpopular with both the Army and the people; facing a rising tide of republicanism he retired to Paris, where he soon died. Municipal elections held in 1931 sent a clear message to King Alfonso: he too was no longer wanted. Declaring that he was ‘determined to have nothing to do with setting one of my countrymen against another in a fratricidal civil war,’ he too went into exile. To widespread celebration – but also some trepidation – the Second Republic was declared.

For much of the population, expectations were enormous. A general election saw a landslide victory for the parties of the Republican-Socialist coalition. Immediate improvements followed: women received the vote, divorce was legalized, land and labour laws were reformed, with attempts made to redistribute land from the large estate owners to the peasants who actually tilled the soil; hom...