eBook - ePub

The Rise and Fall of Khoqand, 1709-1876

Central Asia in the Global Age

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book analyzes how Central Asians actively engaged with the rapidly globalizing world of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In presenting the first English-language history of the Khanate of Khoqand (1709–1876), Scott C. Levi examines the rise of that extraordinarily dynamic state in the Ferghana Valley. Levi reveals the many ways in which the Khanate's integration with globalizing forces shaped political, economic, demographic, and environmental developments in the region, and he illustrates how these same forces contributed to the downfall of Khoqand.

To demonstrate the major historical significance of this vibrant state and region, too often relegated to the periphery of early modern Eurasian history, Levi applies a "connected history" methodology showing in great detail how Central Asians actively influenced policies among their larger imperial neighbors—notably tsarist Russia and Qing China. This original study will appeal to a wide interdisciplinary audience, including scholars and students of Central Asian, Russian, Middle Eastern, Chinese, and world history, as well as the study of comparative empire and the history of globalization.

To demonstrate the major historical significance of this vibrant state and region, too often relegated to the periphery of early modern Eurasian history, Levi applies a "connected history" methodology showing in great detail how Central Asians actively influenced policies among their larger imperial neighbors—notably tsarist Russia and Qing China. This original study will appeal to a wide interdisciplinary audience, including scholars and students of Central Asian, Russian, Middle Eastern, Chinese, and world history, as well as the study of comparative empire and the history of globalization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Rise and Fall of Khoqand, 1709-1876 by Scott C. Levi,Scott Levi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

A NEW UZBEK DYNASTY, 1709–1769

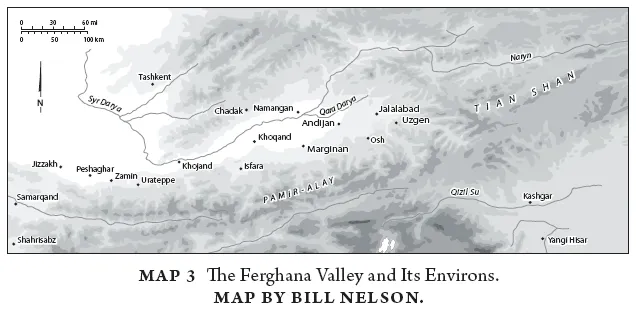

IN THE NORTHWESTERN part of the Ferghana Valley, a small stream flows southward, bringing snowmelt from the distant peaks into the open plains. Observed from a distance, the brown, dusty landscape is interrupted by a shock of green as agriculture becomes possible along a long, narrow strip of land stretching little more than a hundred yards to either side of the frigid water. Moving closer, one spies neatly whitewashed houses tucked beneath ancient trees, a small stone mosque with goats grazing in its courtyard, a dirt road that follows the twisting and turning path of the stream, and farmers tending to their melon patches, vineyards, apple orchards, peach trees, and more. As in other places in the valley, the long and intensely hot summers combine with rich soil and a reliable supply of water from melting snow to provide an ideal environment for growing the intensely sweet fruit for which the region is famous. The trees also provide shade for the inhabitants of this small settlement of Chadak and the khojas, descendants of a lineage of Naqshbandi sufis, who lived among them.

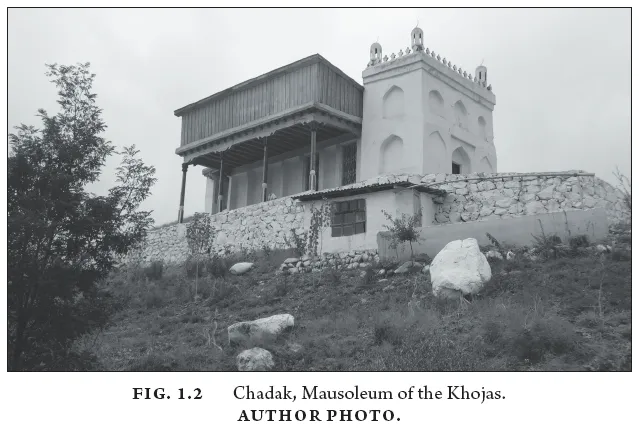

Near the turn of the eighteenth century, the Uzbek amirs and other tribal powers in the region were not the only groups to take advantage of the diminished strength of the Bukharan Khanate. As Bukharan authority withdrew from the Ferghana Valley in the late seventeenth century, political power became localized in the hands of several Turkic tribes and a network of theocratic khojas centered in Chadak. While a number of these tribes, including the Ming, were relatively recent arrivals, the tension between the pastoral-nomadic tribes and the Islamic religious establishment was nothing new. Across western Central Asia, Naqshbandi sufi networks had been heavily engaged in the political arena since the fifteenth-century Timurid era.1 And in nearby Kashgar, to the east, political authority had for decades been in the hands of two rival lineages of Naqshbandi khojas, established by Ishaq Khoja (d. 1599) and Afaq Khoja (d. 1694). Both were descendants of the famous Naqshbandi sufi Ahmad Kasani (1461–1542), renowned as Makhdūm-i A‘zam, the “Greatest Master,” who lived in Samarqand and was reputedly a sayyid, or descendant from the Prophet Muhammad.2

In the late sixteenth century, these sayyid khojas of Kashgar began to usurp authority from the nomadic Chaghataids, descendants of Chinggis Khan. Their influence grew and, by the late seventeenth century, the khojas had effectively replaced longstanding concepts of legitimacy based on steppe traditions with more theocratic concepts based on adherence to Naqshbandi interpretations of Islamic law and practice. In 1678, Galdan Khan (r. 1676–97), the Buddhist ruler who united the Jungar Mongols, defeated the Chaghataids and conquered Altishahr. While the region was made Jungar territory, Galdan Khan installed the leaders of the Afaqiyya (followers of Afaq Khoja, and also known as the Aqtaghlik or “White Mountain” Khojas) to serve as his subordinate governor of Altishahr, the “Six Cities” region of eastern Turkestan.3 For eight decades prior to the Qing conquest of the region, political and religious authority in Altishahr were bound together in the hands of the khojas of Kashgar. The evidence presented in the Khoqand chronicles—albeit scanty, based on oral traditions, and codified well after the fact—suggests that the khojas of Chadak intended to follow in the footsteps of their eastern counterparts by replacing the Bukharan Khanate’s Chinggisid authority with a similar theocracy in the Ferghana Valley. The khojas enjoyed some early successes in the wake of the Bukharan withdrawal in the late seventeenth century, but in the first decade of the eighteenth century the Ming thwarted their efforts.

There are no contemporary accounts of Shah Rukh (r. 1709–22), the Ming tribal leader who is identified as the progenitor of the ruling dynasty that later produced the khans of Khoqand. Chroniclers have, however, preserved several divergent versions of the rich oral history of the events surrounding his rise to power. According to this tradition, the elders of several of the Turkic tribes in the valley assembled early in the eighteenth century to assess their position vis-à-vis the Chadak Khojas. Citing the Tārīkh-i Turkestān, a source authored in 1915, the historian of Khoqand Haidarbek Bababekov identifies the coalition as constituting representatives from “Targhovaga, Jankat, Pilakhan, Tufantip, Partak, Tepe-Kurgan, Kainar and other towns.”4 Specific details regarding the alliance are lacking, but the Uzbek council reportedly decided to unite under Shah Rukh’s leadership to rebel against Chadak and claim political authority from the khojas. The following is a distilled and combined summary of several different accounts as they have come down to us through oral tradition, relying most heavily on Niyazi’s Tārīkh-i Shahrukhī.

The Sultanate began with Shah Rukh, son of ‘Ashur Biy.5 Up to that time, there was no city of Khoqand. Chadak had become a center of power in the Ferghana Valley, and many khojas in that area supported its political position. At the same time, Uzbek tribes had begun to make their way into the valley and gather in various places. The Uzbeks decided that they would come together to make a council. One man announced, “Among us there is a man who is a descendant of Chamash Biy, he is Shah Rukh son of ‘Ashur Bek. We shall make him khan and rebel against Chadak.” The assembled Uzbeks agreed, and they devised a plan to achieve that goal.

The plan began with an effort to convince the Chadak Khojas that they were prepared to establish an alliance and accept a subordinate role to the khojas. Toward this goal, the Uzbeks offered one of their girls to the hakim (governor) of Chadak to take as his wife. The hakim was pleased, and he agreed. On the wedding day, a group of forty Uzbeks came to Chadak to participate in the toi (wedding celebration). After the festivities, the Uzbeks were divided up and placed in various homes as guests. According to the plans that the Uzbeks had laid out, shortly after the groom should arrive that night, but before he would have a chance to consummate the marriage, one of the Uzbeks would rub a willow branch in the crook of a tree to issue a secret signal. At that moment, all of the Uzbeks would rise up and kill their hosts. This was done, and the rise to power of the Chadak khojas was brought to an end.

From Chadak, the Uzbeks rapidly extended their reign (eastward) over Chust and Namangan, and then on to Shaidon and Panghaz (“Pansad Ghazi”). The Uzbeks distributed gifts to the populations of those conquered cities that submitted without resistance, and Shah Rukh appointed hakims to govern them.

Shah Rukh then issued an order that, before searching out and defeating other enemies in the region, his followers should find a place to build a fortress that might serve as their new capital. He sent scouts around the valley and they found an old ruined fortress known as Koktonliq Ata at the juncture of two small rivers, a distance of some sixteen farsakh (about eighty-eight miles) west of Andijan. Shah Rukh ordered the construction of a new ark at that spot.

The Sultanate Is a Garden

Without a Wall, It Is Difficult to Protect

Shah Rukh had a wall built around the city with gates on all four sides: the Andijan Gate in the east, the Namangan Gate in the north, the Tashkent Gate in the west (also called the Khojand Gate, or the Samarqand Gate), and the Ispara Gate in the south (also known as the Chahar Kuh Gate). He ordered residences to be built within the ark for all of the high officials of his new state. The throne was established there, and the Uzbeks commemorated the event with a great celebration. Shah Rukh was installed as khan by the āq kigīz ceremony (the traditional Mongolian “White Felt” ceremony for elevating a Chinggisid khan). The year was 1121 (1709/10). People migrated to this fortress from all around, and the bazaar and surrounding areas grew large and became a city.6

In chapter 5 we will return to the relevance of tracing Shah Rukh’s lineage through Chamash Biy (also referenced in historical sources as Chamash Sufi, Jamash Biy and Shah Mast Biy). For now, it is sufficient to note that doing so served two purposes. The historical Chamash Biy was believed to have been a murid (disciple) of the revered sixteenth-century Naqshbandi sufi Lutfallah Chusti.7 Beisembiev repeats a tradition that Chusti “allegedly had given Chamash the good news that his posterity would be rulers.”8 At the same time, this legend goes on to trace the Shahrukhid lineage through the historical Chamash Biy to the mythical Altun Beshik and, through him, to Babur.

Shah Rukh’s victory over Chadak and the elimination, or more accurately suppression, of the khojas is presented as if it were a momentous event. The resulting image is one of an Uzbek dynasty on an upward trajectory. In the greater context of the region, if the event did in fact unfold as reported through this oral tradition, it reflects nothing more than the good fortune of one Turkic political group—or for want of a better word, tribe—the Ming, in their efforts to take advantage of Bukhara’s weakened stature even prior to the beginning of Abu’l Fayz Khan’s long and ultimately failed reign.

A critical perspective exposes a number of problems with this narrative. For example, although it is possible that Shah Rukh led the coalition of Uzbek tribes that defeated the Chadak Khojas, the historical evidence shows that sufis remained exceptionally powerful in the valley through the duration of the history of the khanate that he launched. Over a century later, a different line of Naqshbandi khojas held sufficient influence to issue multiple campaigns against the Qing in Kashghar, even taking the city in the 1826 and asserting their own rule for some months.9

Two more problematic aspects of the chroniclers’ treatment of this account demand attention. First, the assertion that the Ming elevated Shah Rukh as khan is most certainly an invention of a later period. The Shahrukhids were not Chinggisids and, contrary to what some scholars have argued, they never sought to claim legitimacy by concocting a fictive Chinggisid lineage.10 Rather, during the early eighteenth century, Shah Rukh emerged as one of a number of Uzbek tribal biys (nobles), who enjoyed positions of authority in the Ferghana Valley.11 It does seem that Shah Rukh established an initial capital at what had been a ruined fortress in Deqan Tudah, some three farsakh (about seventeen miles) south of Khoqand.12 But there is no presently reason to challenge the accepted position that Laura Newby has recently examined and reaffirmed, that Shah Rukh’s great-great-grandson ‘Alim was the first of his lineage to claim the title of khan, and that he did so at the very beginning of the nineteenth century for specific reasons pertaining to foreign diplomacy initiatives and his conquest of Tashkent.13

Equally implausible is the suggestion that Shah Rukh governed over a vast stretch of the Ferghana Valley. Based on the available information, it is reasonable to conclude that Shah Rukh successfully extended his control over some of the central and western portions of the Ferghana Valley. However, the extent of his territory is questionable, the sources do not address the degree of autonomy that his hakims enjoyed, and the centralization of whatever administration he did establish was quite limited and would remain that way for decades to come. Again, one must resist the temptation to read backward later achievements and assign any form of centralized statehood to Khoqand at this stage in its development. The chronicles attest to the Shahrukhids’ impressive number of early military victories, but they neglect to place an equal emphasis on the fact that many of these were temporary and throughout the history of Khoqand power and authority were matters of constant negotiation. In general, it is necessary to approach concepts of statehood in Central Asia during this period with great caution and sensitivity to the teleological nature of the sources. One thing we can assert with a reasonable degree of certainty is that the Shahrukhids did not bring the entire Ferghana Valley under their control in any meaningful way until much later in the eighteenth century.

Also problematic is that the above is not the only account of Shah Rukh’s rise to power. Niyazi and Muhammad Fazl Bek both present versions of an alternate tradition that, when Shah Rukh was eighteen years old, one of the “Khans of Mawarannahr” traveled to the Ferghana Valley to go lion hunting (at that time the Toqay-Timurid ruler of Bukhara would have been either Subhan Quli Khan, r. 1681–1702, or his son and successor ‘Ubaydullah Khan, r. 1702–11). Shah Rukh accompanied the khan into a forested area of the valley where the hunting party encountered a lion. The young Shah Rukh leaped forward and, engaging the beast, mortally wounded it with a dagger (or a spear). Shah Rukh’...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: Connecting Histories

- Acknowledgments

- Transliteration and Abbreviations

- The Shahrukhid Rulers

- Note on Geographic Terminology

- Note on Sources

- Introduction

- 1. A New Uzbek Dynasty, 1709–1769

- 2. Crafting A State, 1769–1799

- 3. The Khanate of Khoqand, 1799–1811

- 4. A New “Timurid Renaissance,” 1811–1822

- 5. A New Crisis, 1822–1844

- 6. Civil War, 1844–1853

- 7. Khoqand Defeated, 1853–1876

- Conclusion

- General Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index