![]()

CHAPTER 1

FOUNDING PRINCIPLES OF CLASSICAL BALLET

Ginny Brown

Ballet is one of the most popular dance styles in the world. There are ballet companies based in most major cities, principal ballet dancers have become household names and each week millions of children learn ballet at local dance schools. The spectacle of ballet, with its super-human skill and extraordinary synthesis of aural and visual splendour, offers entertainment and escape. But a deeper attraction, I believe, is that the underlying classical principles of ballet are based on the laws of nature and the human form. So when we watch or perform ballet, the harmony of the shape and movement feels intuitively ‘right’.

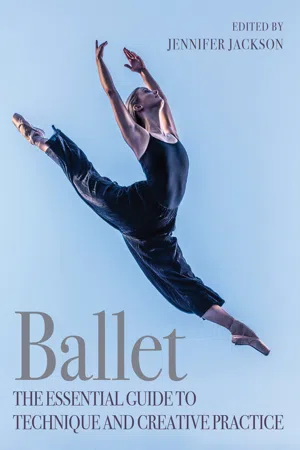

Marianna Tsembenhoi and James Large, Royal Ballet (Upper) School students performing Sea Interludes by Andrew McNicol at the Royal Opera House.

Yet with its highly specialized technique and long history, ballet can appear inaccessible and difficult to understand. The physical challenges take time and perseverance to master, and its codified language requires specialist study. Therefore, ballet is often perceived as an elite activity – traditionally only enjoyed by those who have spent years learning about the art form and who have been able to pay for the privilege! But this need not be the case. The beauty of ballet is that the classical principles, at its heart, are fundamentally connected to our natural human movement potential. These classical principles, which underpin both the codified technique and the ballet repertoire, can provide an understandable entry point into this complex and physically demanding dance style. By exploring these foundations, this chapter aims to inspire the experienced dancer and teacher to reconnect with the fundamental principles that shape the art form, as well as offering a starting point from which inexperienced dancers can understand, embody and enjoy the classicism of ballet.

CLASSICAL PRINCIPLES

Like all classical art forms, ballet draws on the classical ideals of balance, harmony and proportion. These qualities are found throughout nature, including in the human body, which is naturally vertical, symmetrical and balanced. Therefore, when learning or teaching ballet it is liberating to remember that, whilst the technical movement may be challenging to master, it is also firmly rooted in the natural design of our bodies.

The Golden Section

These classical principles can be described by a set of geometric proportions known as the Golden Section or the Divine Proportion. Mathematically, the Golden Section proposes a particular relationship between the parts and the whole, and is most easily understood when illustrated as a straight line.

The whole (AC: 1.618) to the longer (AB: 1) as the longer (AB: 1) is to the shorter (BC: 0.618).

Using these proportions, a rectangle can be drawn with ever decreasing segments. A golden spiral is formed by connecting the rectangles.

This straight line is divided approximately into three-fifths and two-fifths. This same proportion can be found in our own bodies and relates to the famous Fibonacci series of numbers.1 For example, try measuring the length of your body from head to feet (AC). Then measure the length from your navel to feet (AB) and from navel to head (BC). You should find that the proportions broadly match those of the illustrated line (the length from head to navel is approximately two-fifths of your total height and the length from navel to feet is approximately three-fifths).

Patterns in Nature

These proportions give rise to a series of shapes and dynamics that appear throughout nature from the uncurling of a leaf, to the spiral of a galaxy. They form principles of harmony that have been acknowledged as fundamental truths. They are reflected in the proportions of our bodies – not only in the ratio of one body part to another, but in whorls of hair, our fingerprints and in the spiral of the inner ear canal. These proportions have also been used by architects to produce buildings of outstanding beauty: from the pyramids of Egypt, to the Parthenon in Athens, European Gothic cathedrals and even modern buildings, such as the Gherkin in London.2 So let’s consider how ballet employs these principles of balance, harmony and logical order to shape the design of the body and its movement through time and space.

Geometric Patterns

Leonardo da Vinci illustrated this, the first known treatise on the Divine Proportion, by Luca Piacolli. Da Vinci’s drawing depicts the perfect proportions of the human body. The man’s body is symmetrical either side of the vertical axis. The figure is inscribed within a circle and a square – the fundamental geometric patterns that inform classical ballet. All the movements that your body performs in ballet take place within an imaginary circle (your kinesphere) and in relation to an imaginary square (the dancer’s square).

Vitruvian Man, one of Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous drawings, depicts the perfect proportions of the human body.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Ballet’s interest in the classical principles of refining and formalizing natural patterns into geometric designs can be traced right back to its inception. Ballet began in the Renaissance, in the French and Italian courts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, where dancing was considered a noble skill for royalty and courtiers. These court dances drew inspiration from local folk dance – the dance of the people – which, in turn, reflected patterns in nature, such as circling, spirals, opening and closing, advancing and retreating. This connection to nature can be traced through ballet’s history – in the earthly scenes of Romantic ballets, the stylized character dances of Petipa’s classical ballets and in the pagan ritual portrayed in Nijinsky’s revolutionary Rite of Spring.

Verticality

Ballet begins with one of the unique features of the human body – our verticality. Standing still, we can sense a straight line running vertically through the body – from the centre of the head, through the torso and down between the two feet. This imaginary vertical line allows you to feel your weight in relation to gravity and so remain balanced and ‘centred’ (en place). This concept is so fundamental to ballet that moving up and down the vertical ‘plumb line’ (aplomb) is the first thing a ballet dancer practices every day in the form of plié (to bend). A distinctive feature of ballet is how the dancer then utilizes this verticality to resist gravity in order to balance, spin and leap.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

From the early flowering of ballet at the court of the French King Louis XIV, upright stance (with feet firmly planted on the ground but head reaching toward the heavens) was employed to create an illusion of divine presence. Use of the vertical ‘plumb line’ was then refined and extended during the romantic ballet period to create the illusion of ethereal, weightless creatures. Advances in technical skill enabled the dancer to perform sustained balances, resulted in the development of pirouettes (turns), slow, graceful adage movements, such as arabesques, and higher elevation and the introduction of pointework (the female dancer balancing on the tips of her toes). Classical ballet’s pas de deux (duet) then took the dancer’s verticality to spectacular new heights. The ballerina’s pointework evolved into a technical feat, the male dancer performed soaring leaps and together they created impressive lifts, virtuoso turns and extraordinary balances.3

Turn Out

In order to create a wider range of movement, the ballet dancer rotates the arms and legs outwards around their imaginary vertical axis. This twisting action of the opposing muscles, which are activated in rotation, creates spirals in the body and results in the turned out positions of the legs and feet. Five formal, outwardly rotated, positions create the start and end of every movement in ballet. This outward rotation also enables the dancer to extend their limbs well beyond the usual anatomical limit. The combination of verticality and outward rotation leads to movements on horizontal and vertical planes, and particularly to movements of the legs directed to the front, side and back. This pattern is formalized as en croix (in the shape of a cross), which is practised in the second exercise of ballet class – battements tendus (leg stretches).4

By connecting the points of the cross, the limbs trace circular patterns – en dehors (outwards, with a feeling of moving away from the centre of the body) and en dedans (inwards, with a feeling of moving toward the centre of the body). These circular movements of the arms and legs trace the three-dimensional periphery of the kinesphere, resulting in twisting spirals and movements that open and close – mirroring natural rhythms, such as breathing. Movements en dehors and en dedans are practised in ballet class as ronds de jambe (circles with the leg) and ports de bras (movements with the arms). Spinning around the vertical axis is then utilized later in the class in the performance of pirouettes.

The line of aplomb implies a centre or still point from which movement may move out, to which it will return and which will be present throughout. ‘En-dehors’, ‘En-dedans’, ‘En place’: the outward movement, the inward movement, and being in place; these are the three great expressions of the classical dance.5

Choreographers often use these opening and closing movements to create light and shade in the dance; to portray emotion, mood and meaning. For the dancer, the feeling that is evoked when you take time to experience these geometries is personal to you – so the principles of en dehors, en dedans, en place and en croix...

-plgo-compressed.webp)