![]()

Introduction

Time, Space, Source Material, and Methods

At the end of the second century B.C., Athenian worshippers set out in procession, marching from Athens to the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi to celebrate the Pythais festival. The pageant was held in a grand manner “worthy of the god and his particular excellence.” One individual stood out among the participants: Chrysis, priestess of Athena Polias. For her role in making the occasion one that befitted both Athens and Delphi, the people of Delphi bestowed upon Chrysis the crown of Apollo. The city also voted to grant her, as well as all her descendants, an impressive series of rights and privileges: status as a special representative of Athens to Delphi (proxenos), the right to consult the oracle, priority of trial, inviolability (asylia), freedom from taxes, a front seat at all competitions held by the city, the right to own land and houses, and all other honors customary for proxenoi and benefactors of the city.1

Back in Athens, Chrysis’s cousins, Dionysios, Niketes, and Philylla, set up a statue of their famous relative on the Acropolis. They themselves were prominent Athenians from a family distinguished by its numerous cult officials. Chrysis had a great-great-grandfather who was a sacred supervisor (epimeletes) of the Eleusinian Mysteries and a grandfather who was a priest of Asklepios.2 The decree set up by the people of Delphi and the statue base from the Athenian Acropolis provide a tantalizing glimpse into the life of an exceptional woman. While scores of inscriptions survive to honor men in this way, Chrysis stands out as one of the few women who received special privileges by decree.3 Her public record brought substantial rights for her and all her descendants. She further enjoyed the honor of having her statue set up on the Athenian Acropolis, ensuring that she would be remembered always in her priestly status.

Despite wide contemporary interest in the role of women in world religions, the story of the Greek priestess remains elusive. Scattered references, fragmentary records, and ambiguous representations confound attempts to form a coherent view of women who held sacred offices in ancient Greece. Yet the scope of surviving evidence is vast and takes us through every stage on the path through priesthood. It informs us about eligibility and acquisition of office, costume and attributes, representations, responsibilities, ritual actions, compensation for service, authority and privileges, and the commemoration of priestesses at death. Only by gathering far-flung evidence from the epigraphic, literary, and archaeological records can we recognize larger patterns that reveal the realities of the women who held office. This evidence provides firm, securely dated documentation from which we can bring to life the vibrant story of the Greek priestess.

This narrative is particularly important because religious office presented the one arena in which Greek women assumed roles equal and comparable to those of men. Central to this phenomenon is the fact that the Greek pantheon includes both gods and goddesses and that, with some notable exceptions, the cults of male divinities were overseen by male officials and those of female divinities by female officials. 4 The demand for close identification between divinity and cult attendant made for a class of female sacred servants directly comparable to that of men overseeing the cults of gods. Indeed, it was this demand that eventually led to a central argument over the Christian priesthood, exclusively granted to male priests in the image of a male god. As Simon Price has stressed, the equality of men and women as priests and priestesses in ancient Greece was nothing short of remarkable.5 In a world in which only men could hold civic office and enjoy full political rights, it would have been easy enough for cities to organize their priesthoods on the model of magistracies. But the power of gender in the analogy between sacred servant and deity was so strong that it warranted a category of female cult agents who functioned virtually as public-office holders. Price has challenged us to consider the deeper question of why the Greeks so emphasized both genders for their gods.6 We will take up this line of inquiry in chapter 2.

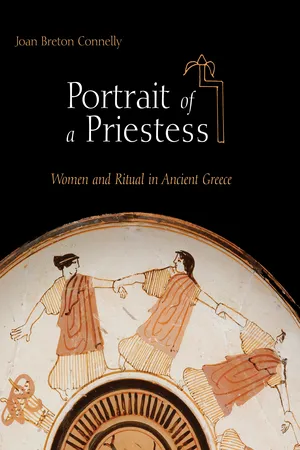

Evidence for priestesses can be found in nearly all categories of Greek texts, from Linear B tablets to epic and lyric poetry, histories, tragedies, comedies, political speeches, legal documents, public decrees, and antiquarian commentaries.7 Inscribed dedications attest to the generosity of priestesses in making benefactions to cities and sanctuaries, their pride in setting up images of themselves, and their authority in upholding sanctuary laws. Inscriptions also provide evidence that these women were publicly honored with gold crowns, portrait statues, and reserved theater seats. Priestesses are represented in nearly every category of visual culture, including architectural sculpture, votive statues and reliefs, funerary monuments, vases, painted shields, wooden plaques, and bronze and ivory implements. In the face of this abundant evidence it is hard to understand how the prominent role of the Greek priestess has, until recently, been ignored by modern commentators or, worse yet, denied.8

Never before has the archaeological evidence for priestesses been systematically examined within the broader context of what is known from the epigraphic and literary spheres. From the late nineteenth century, inscriptions have been the primary source for our understanding of ancient priesthoods.9 In her dissertation of 1983, Judy Ann Turner brought together wide-ranging epigraphic evidence for feminine priesthoods, focusing largely on the acquisition of sacred offices.10 In 1987, Brunilde Ridgway pioneered the study of material evidence for women in ancient Greece, including images of female cult agents.11 Alexander Mantis’s comprehensive monograph on the iconography of priesthood, male and female alike, followed in 1990.12 This groundbreaking work brought together a wide corpus of images, many of which had been unknown. In the years that have followed, additional monuments representing priestesses have been published, and broader studies on women and religion have made some limited use of visual material.13 In her important study of priesthoods, dedications, and euergitism, Uta Kron has called for the viewing of archaeological and epigraphic data together with and in contrast to what we know from literary sources.14

A central contribution of Portrait of a Priestess is the recognition of the authority of the archaeological record and its integration into our broader understanding of the women who served Greek cults. In this, I follow Anthony Snodgrass, Gloria Ferrari, Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood, and others who have emphasized the independent existence of the archaeological record from the textual tradition that has, in so many ways, subordinated it.15 As the long-neglected visual material has its own history, its own “language,” motivations, and influences, we should not expect it to illustrate facts recorded in texts. Instead, it will be seen to reflect aspects of priestly service not preserved elsewhere, significantly broadening our understanding of sacred-office holding. In many cases, it contributes evidence for periods and regions that do not have the benefit of a surviving textual heritage. Beyond this, archaeological and epigraphic evidence sometimes can be seen to contradict the picture given in literary sources. It thus provides an important correction to the distorting effects of the voice, intent, and context of the author, as well as the accidents of survival and the benefits of privilege that have focused our attention on only a fraction of the original corpus of texts.

Two important developments in scholarly thinking have made conditions ripe for a seasoned and comprehensive review of the evidence for Greek priestesses. One is a reassessment of the alleged seclusion of women in classical Athens and the implications of this for our understanding of their public roles. The other is a new questioning of the validity of the category of regulations called “sacred laws,” long viewed as distinct and separate from the larger body of legislation within the Greek polis. This opens the way for understanding female cult agents as public-office holders with a much broader civic engagement than was previously recognized. These two paradigm shifts make for a fresh and forward-looking environment in which we can evaluate the evidence, one that allows for a new understanding of the ancient realities of priestly women.

First, let us track developments on the question of the “invisibility” of women. Over the past thirty years, it has become a broadly accepted commonplace that Athenian women held wholly second-class status as silent and submissive figures restricted to the confines of the household where they obediently tended to domestic chores and child rearing.16 This has largely been based on the reading of certain well-known and privileged texts, including those from Xenophon, Plato, and Thucydides, and from certain images of women portrayed in Greek drama.17 The consensus posture of this view has, to a certain extent, been shaped by the project of feminism and its work in recovering the history of gender oppression.

While there have been some voices of dissent from early on, the chorus of opponents to this oversimplified position has grown steadily over the years, gathering strength from the economic, political, and social/historical arenas.18 Already in the 1980s, David Cohen stressed the importance of distinguishing between “separation” and “seclusion,” and pointed out serious contradictions between cultural ideals and real-life social practices.19 Edward Harris has now elucidated the active role of women in the economic sphere, where they exercised informal, but highly effective, methods for influencing decisions about money.20 Lin Foxall has shown that women had considerable control over property within their households, particularly those women who brought large dowries, and took initiatives in economic matters in which they held a vested interest.21 Examining archaeological remains from domestic contexts, Lisa Nevett and Marilyn Goldberg have offered a new understanding of gendered space and the regulation of social relations within the Greek household.22 Josine Blok has shown that women’s public speech in Athens had everything to do with where they were and when they were there.23

Jeffrey Henderson and Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood have made compelling cases for the presence of women at dramatic performances in Greek theaters, despite a modern reluctance to accept it.24 Early on in the debate, Cynthia Patterson considered the possibility of citizen identity for women described as hai Attikai.25 Josine Blok has now argued on linguistic grounds that Athenian women of citizen families were, in fact, recognized as citizens. Importantly, she has shown that their leadership roles in matters of cult were, in effect, political offices that directly engaged women with the broader enterprise of politeia.26

Even those who persist in maintaining an “invisibility” for Athenian women recognize that cult worship offered the single stage on which women could enjoy some measure of prominence. But this religious stage has too often been dismissed as secondary and peripheral to the political and economic nucleus of the polis. This attitude is clearly a product of our own contemporary cultural biases and has nothing to do with the realities of the ancient city. By marginalizing the importance of sacred-office holding, interpreters persist in presenting a pessimistic picture of the possibilities for Athenian women, subjected to utterly passive roles in an entirely secondary status.

This is why new developments in our understanding of so-called sacred laws are so important. Each sanctuary had its own rules and regulations to dire...