- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

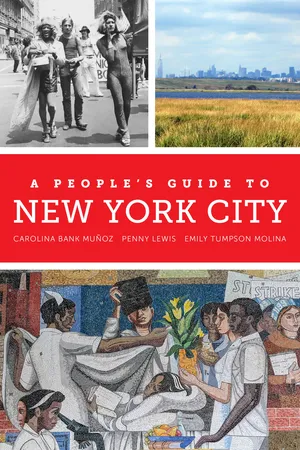

A People's Guide to New York City

About this book

This alternative guidebook for one of the world’s most popular tourist destinations explores all five boroughs to reveal a people’s New York City.

The sites and stories of A People’s Guide to New York City shift our perception of what defines New York, placing the passion, determination, defeats, and victories of its people at the core. Delving into the histories of New York's five boroughs, you will encounter enslaved Africans in revolt, women marching for equality, workers on strike, musicians and performers claiming streets for their art, and neighbors organizing against landfills and industrial toxins and in support of affordable housing and public schools. The streetscapes that emerge from these groups' struggles bear the traces, and this book shows you where to look to find them.

New York City is a preeminent global city, serving as the headquarters for hundreds of multinational firms and a world-renowned cultural hub for fashion, art, and music. It is among the most multicultural cities in the world and also one of the most segregated cities in the United States. The people that make this global city function—immigrants, people of color, and the working classes—reside largely in the so-called outer boroughs, outside the corporations, neon, and skyscrapers of Manhattan. A People’s Guide to New York City expands the scope and scale of traditional guidebooks, providing an equitable exploration of the diverse communities throughout the city. Through the stories of over 150 sites across the Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island as well as thematic tours and contemporary and archival photographs, a people’s New York emerges, one in which collective struggles for justice and freedom have shaped the very landscape of the city.

The sites and stories of A People’s Guide to New York City shift our perception of what defines New York, placing the passion, determination, defeats, and victories of its people at the core. Delving into the histories of New York's five boroughs, you will encounter enslaved Africans in revolt, women marching for equality, workers on strike, musicians and performers claiming streets for their art, and neighbors organizing against landfills and industrial toxins and in support of affordable housing and public schools. The streetscapes that emerge from these groups' struggles bear the traces, and this book shows you where to look to find them.

New York City is a preeminent global city, serving as the headquarters for hundreds of multinational firms and a world-renowned cultural hub for fashion, art, and music. It is among the most multicultural cities in the world and also one of the most segregated cities in the United States. The people that make this global city function—immigrants, people of color, and the working classes—reside largely in the so-called outer boroughs, outside the corporations, neon, and skyscrapers of Manhattan. A People’s Guide to New York City expands the scope and scale of traditional guidebooks, providing an equitable exploration of the diverse communities throughout the city. Through the stories of over 150 sites across the Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island as well as thematic tours and contemporary and archival photographs, a people’s New York emerges, one in which collective struggles for justice and freedom have shaped the very landscape of the city.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A People's Guide to New York City by Carolina Bank Muñoz,Penny Lewis,Emily Tumpson Molina in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Historische Geographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Bronx

Introduction

IN OCTOBER OF 1977, PRESIDENT JIMMY Carter visited a stretch of Charlotte Street near Boston Road in the heart of the South Bronx. He stood amid rubble on a vacant lot, flanked by eight-foot-high piles of bulldozed brick. Behind him were the remnants of a block of five-story walkup apartment buildings, charred and missing windows, some boarded, others spookily exposed. Carter brought the world’s eyes to the South Bronx in the late 1970s, which came to stand as the national symbol of urban blight and decay, a stark reminder of the “failure” of the nation’s cities in the wake of the civil rights movement.

Carter also headed about ten blocks down the road to visit 1186 Washington Avenue. There, Bronx resident Ramon Rueda led the nascent People’s Development Corporation (PDC) to renovate a six-story tenement with forty volunteer homesteaders. Rueda believed that if the people of the Bronx were given adequate resources, they could reclaim abandoned buildings and revitalize them, fueled as well by their sweat equity and deep commitment to the borough. The PDC was one of dozens of community groups working to improve and rebuild their beloved Bronx in the late 1970s—a place of mass devastation but also of unparalleled fertility, where the people’s culture thrived, where jazz and doo-wop music had flourished, where salsa grew and hip-hop culture was born. Disinvestment, resilience, organizing, innovation: all frameworks for understanding today’s Bronx.

Bronx is the city’s northernmost borough—across the Harlem River from uptown Manhattan and across the East River from northern Queens—and the only part of New York City on the US mainland. It borders affluent Westchester County, and, in keeping with its neighbors, the northern part of the borough is home to some of New York City’s most affluent communities. Riverdale and Fieldston, just west of Van Cortlandt Park, have some of the highest median incomes in New York City, as do Pelham Bay/Gardens and the surrounding communities along the borough’s eastern coast. Fieldston is one of a handful of privately owned neighborhoods within New York City limits, with maintenance provided by the property owners’ association rather than the city (another is Forest Hills Gardens, in Queens).

Much of the rest of the Bronx is poor or working class. Poverty and unemployment rates in the borough are consistently the city’s highest, and its residents the least educated of all the boroughs. But since the height of deindustrialization and unemployment in the 1970s, the Bronx has seen a steady increase in employment opportunities, particularly in health care, retail, social services, and food service. The health-care industry—including Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center, Calvary Hospital, James J. Peters VA Medical Center, and Montefiore Medical Center—constitutes the largest source of jobs in the borough. But poverty and unemployment rates remain stubbornly high.

The Bronx is the only borough in New York City with a Latina/o/x majority, made up primarily of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, with sizable Mexican and Honduran populations as well. It has the smallest concentration of non-Hispanic whites in the city, and a relatively large Black population (43 percent). Nearly 60 percent of residents of the Bronx speak a language other than English at home; almost half of residents speak Spanish at home. The borough is also home to Jamaican, Irish, Ghanaian, Senegalese, and Albanian enclaves, among others.

Remarkably, even though the Bronx is the nation’s third most densely populated borough after Manhattan and Brooklyn, fully one-quarter of the borough is open space, including Pelham Bay Park, the city’s largest public park, and Van Cortlandt Park, which includes the nation’s first public golf course. Despite the vast open space, the Bronx is among the most polluted areas of the city. Traffic pours in and out of Hunts Point, a major food distribution hub that also houses a third of the city’s waste transfer facilities, and along the borough’s major highways. Air pollution is a significant problem in the dense neighborhoods that border the seven highways that crisscross the borough. Asthma rates in the South Bronx are among the nation’s highest.

Today’s Bronx was once known as the Lenapehoking territory, inhabited by the native Siwanoy of the Algonquian-speaking Wappinger Confederacy, until the Dutch colonized it for farmland beginning in 1639. It remained thus until the mid-1800s, when German and Irish immigrants created small suburban communities near new railroad stations in Mott Haven, Melrose, and Morrisania—all part of today’s South Bronx. Rapid transit extended into the Bronx with the elevated Third Avenue line in the final decades of the nineteenth century, along with the city’s streetcar system. After the subway linked Melrose to Manhattan in 1904 and what are now the 1, 2, 4, and 6 train routes began snaking through the Bronx, immigrant workers from crowded East Harlem and the Lower East Side flocked to the Bronx for more space and better housing conditions.

By 1930, the Bronx held nearly 1.3 million people and would have been the fifth largest city in the country had it not already been part of New York—its density was rivaled only by Manhattan. Boosters for Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island built small singlefamily homes, but, by and large, in the Bronx it was large apartment houses that beckoned new residents. By 1940 the Bronx was second only to Manhattan in rental housing and large apartment buildings. Hundreds of thousands of the city’s immigrants aspired to live in the Bronx’s large, modern units, particularly in the West Bronx along the Grand Concourse, with their vast marble lobbies and shiny parquet floors, eat-in kitchens, and tiled bathrooms and kitchens. As Constance Rosenblum (2011) notes, “from the early 1920s through the late 1950s, the Grand Concourse represented the ultimate in upward mobility and was the crucible that helped transform hundreds of thousands of first- and second-generation Americans—mostly Jewish but also Irish and Italian, along with smatterings of other nationalities—from greenhorns into solid middle-class Americans.” The newcomers shopped at the nearby department stores along Fordham Road, went to movies at the luxurious Loew’s Paradise just south of it, and watched their beloved Yankees play in the country’s most famous ballpark. Their children played stickball in the streets and drank egg creams and malteds at the corner candy stores.

While Irish and Italians settled in the Bronx in great numbers between 1920 and 1960, it would come to be known as the “Jewish borough,” with Jews comprising nearly 40 percent of residents by 1940. Hundreds of synagogues and other Jewish cultural institutions dotted the borough. Leftwing Jewish workers founded some of the most important cooperative housing projects in the nation there (see The “Allerton Coops, Amalgamated Housing Cooperative, Co-op City).

Those with means followed the new subway lines north and into the neighboring West Bronx, including Morris Heights, University Heights, Kingsbridge, and Highbridge —places that were largely closed to Black and Latina/o/x New Yorkers at that time. White flight from the South Bronx pushed landlords in the Mott Haven, Morrisania, Melrose, and Hunts Point-Crotona Park East communities to begin renting to upwardly mobile Black residents from Harlem, new Black migrants from the Jim Crow South and the Caribbean, and Puerto Ricans escaping economic depression on the island. These neighborhoods were the oldest, most dilapidated, and poorest parts of the borough. But they also facilitated the melding and mixing of these groups, particularly in the 1940s and 1950s with the white ethnics who stayed. Morris High School in Morrisania, historian Mark Naison (2016) notes, “was perhaps the most integrated secondary school in the United States” during this time.

Still, over a ten-year period, the South Bronx went from being two-thirds white in 1950 to two-thirds Black and Latina/o/x in 1960, as white flight from the entire borough began to take hold. This, coupled with the loss of industry from the city, utterly transformed the borough in the 1960s and 1970s. Racism and federal policies that supported homeownership in white suburbs pulled the white ethnics, who had once strongly supported the city’s strong network of public services, out of most points south of Fordham Road and pushed them to newly constructed Co-op City, suburban Westchester County, and New Jersey. Unlike in other boroughs, notably Queens, new residents did not make up the difference: between 1970 and 1980, the Bronx lost 20 percent of its population; the South Bronx lost at least 40 percent—and, by some estimates, more than half its residents. Those who stayed contended with rising poverty in the places left behind, the vast majority of them Black and Latina/o/x.

At the same time, the industrial elements of the mixed economy that had supported the Bronx were disappearing by the 1970s. Manufacturers moved from the city to the South or abroad. Shipping moved to the deep water ports at Newark and Elizabeth, New Jersey. And as the city slipped into a fiscal crisis, the Bronx was the borough hardest hit. Between the mid-1960s and 1970s at least half a million New Yorkers lost their jobs. By 1972, around one in eight New Yorkers received public assistance.

As a result ...

Table of contents

- Subvention

- About the Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Introduction

- 1 Bronx

- 2 Manhattan

- 3 Queens

- 4 Brooklyn

- 5 Staten Island

- 6 Thematic Tours

- Reccomended Reading

- Acknowledgments

- Credits

- Index