- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

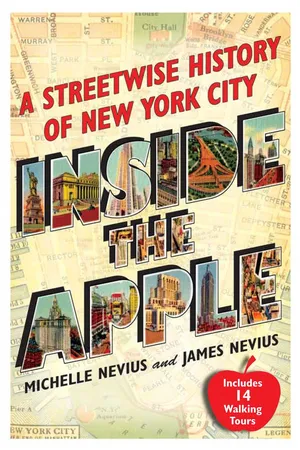

About this book

How much do you actually know about New York City? Did you know they tried to anchor Zeppelins at the top of the Empire State Building? Or that the high-rent district of Park Avenue was once so dangerous it was called “Death Avenue”? This lively and comprehensive guidebook brings New York’s fascinating past to vivid life.

This narrative history of New York City is the first to offer practical walking tour know-how. Fast-paced but thorough, its bite-size chapters each focus on an event, person, or place of historical significance. Rich in anecdotes and illustrations, it whisks readers from colonial New Amsterdam through Manhattan's past, right up to post-9/11 New York. The book also works as a historical walking-tour guide, with 14 self-guided tours, maps, and step-by-step directions. Easy to carry with you as you explore the city, Inside the Apple allows you to visit the site of every story it tells. This energetic, wide-ranging, and often humorous book covers New York's most important historical moments, but is always anchored in the city of today.

This narrative history of New York City is the first to offer practical walking tour know-how. Fast-paced but thorough, its bite-size chapters each focus on an event, person, or place of historical significance. Rich in anecdotes and illustrations, it whisks readers from colonial New Amsterdam through Manhattan's past, right up to post-9/11 New York. The book also works as a historical walking-tour guide, with 14 self-guided tours, maps, and step-by-step directions. Easy to carry with you as you explore the city, Inside the Apple allows you to visit the site of every story it tells. This energetic, wide-ranging, and often humorous book covers New York's most important historical moments, but is always anchored in the city of today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inside the Apple by Michelle Nevius,James Nevius in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

The Early City: New Amsterdam, Colonial New York, the Revolutionary Era, and the Birth of the New Republic, 1608–1804

New York has long had a romance with its early history, which is often depicted through a gauzy lens of nostalgia: stout windmills line the harbor, able-bodied men in tall hats trade beaver skins with the peace-loving Indians, while their wives stand in half doors (still known as Dutch doors), a gaggle of children at their feet. All of it is overseen by the stern hand of “Peg Leg” Peter Stuyvesant, the colony’s curmudgeonly director general.

New York City’s seal, ca. 1686

New York City’s seal today

This is not just the stuff of children’s stories. The city’s picturesque past is even enshrined on its great seal, which dates back to 1686. At its center are the arms of a Dutch windmill, surrounded by symbols of the city’s economic history: top and bottom are beavers, Manhattan’s first great export commodity; left and right are barrels of flour, an important staple during the English period. On either side of the shield are two men: to the viewer’s left, a Dutch/English sailor, who not only represents the city’s importance as a port, but recognizes the idea that all its non–Native American inhabitants have come from across the sea.1 To the viewer’s right is a Native American—decked out in true “noble savage” style, with headdress and bow—representing the people the Europeans displaced. At the top of the seal originally sat a British crown, which was replaced after 1783 with an American bald eagle. Finally, at the bottom of the seal is the date of the city’s founding.

It is difficult, however, to pin down the actual year of the city’s birth. During the British period, the seal was dated 1686, the year Governor Thomas Dongan received an official charter. Later, the date was changed to 1664, the year the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam was conquered by the English and renamed New York. However, in 1975—on what was dubbed the 350th anniversary of the official establishment of New Amsterdam—the date was changed to 1625 to recognize the Dutch contributions to the city’s founding.

But to many, even that date is too late. They push the beginning back to 1609, the year Henry Hudson’s ship Halve Maen entered Manhattan’s harbor, which led to European colonization. (New York has long celebrated this year. It hosted an elaborate Hudson-Fulton Festival in 1909 and a Hudson-Fulton-Champlain festival in 2009.) Of course, by 1609 people had been living in and around what would become modern-day New York City for upward of 11,000 years.

All of which is to say, picking a “beginning” is somewhat arbitrary. For our purposes—since this is a book of history that you can see and experience—we begin with Henry Hudson and the coming of the Dutch. Not only does this reflect the fact that few examples of our geological past are visible, it also points to the more grievous truth that there are hardly any traces left of the city’s long and rich Native American heritage. It’s somewhat heart-stopping to think that Europeans have only inhabited this area for less than four centuries and in that time have erased millennia of human habitation by the Lenape and others who preceded us.

While these first 21 chapters cover a great span of years—nearly half of the city’s European history—each place and story they tell is fundamental to understanding the city. Indeed, examining Manhattan’s early history presents in wonderful microcosm the brash history of young America, which had its economic and political roots firmly tied to New York.

1. The Algonquin-speaking Native Americans who lived here called the Dutch swannekens, meaning “people of salt.” This is generally accepted to mean that the natives recognized the Europeans as people from across the ocean.

1. Manna-hata: New York Before the Europeans

Walking through Times Square, surrounded by concrete, traffic, steel, and neon, it can be difficult to conjure up what this same tract of land must have looked like in 1608—a mere 400 years ago—before the arrival of Europeans. What would we see if we could strip away the generations of urbanization and return Manhattan to its pre-contact glory?

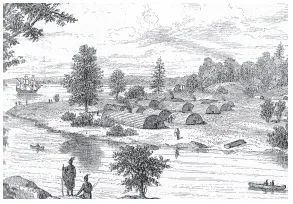

New Yorkers often wonder about what was here before. It can be tempting to invoke an Eden-on-the-Hudson, where wild animals roamed freely through tall forests and verdant meadows. And Manhattan did have all those things—but for nearly 11,000 years before Henry Hudson [2] there were also people using the land and altering it for their own benefit.

At the end of the last Ice Age (ca. 20,000 years ago), the Wisconsin glacier began a slow retreat, revealing the deep fjord that we now call the Hudson River. Exerting tremendous pressure as it moved, the glacier also scraped away layers of sediment, leaving parts of the island of Manhattan with exposed bedrock. This bedrock, called Manhattan schist,1 is easily seen today in Central Park and Morningside Park [73], where vast pieces of rock rise from the ground dramatically. Other remnants of glaciation can also be seen at the southern end of Central Park’s Sheep Meadow [151], where a line of boulders marches from the southwest, crossing the footpath that borders the bottom of the meadow. These are glacial erratics, non-native stones that were deposited here by the ice floe.

As the glacier departed, the first Native Americans were arriving, but very little is known about these settlers. Clovis point spearheads and other stone tools found in Staten Island in the 1950s place people in the area about 11,000 years ago. Scant evidence exists of population migrations and changes over the next 10 millennia, but many archaeologists agree that Native Americans lived in and around the area continuously until the arrival of European settlers. In the 17th century, these inhabitants were part of a larger group of Algonquin speakers; they referred to themselves as Lenape (“the people”) or Munsee (their language group). Tribal names, such as Canarsie or Hackensack, are a European creation, and were likely place names or family groups.

Today, though there are still some Lenape descendants in and around the New York region, the most vivid reminder of the city’s native past can be found in words. The most common of these is, of course, Manhattan—a word that today is known around the world but which has never been adequately defined. Because of differences in dialect and the general inability of most Europeans to correctly hear and reproduce Algonquin words, we will never know for certain what it signified. One Lenape word, menatay, means “island”; another, mahatuouh, is “the place for wood gathering”; and a third, mahahachtanienk, is usually translated as “place of general inebriation.” But none of these are Manna-hata, the first words ever written down by a European to name the island.

A typical European view of a Lenape settlement

In the 19th century, Manhattan was often poetically translated as something along the lines of “island of gentle rolling hills.” However, that translation has given way to a pithier definition, “rock island.” While today the bedrock is really only visible in the parks and a few other places, 400 years ago it would have been the island’s most salient feature, making it distinct from the less rocky, more arable land surrounding it in what we would today call New Jersey and Long Island.

The rivers that surround Manhattan were central to life, from the wide array of fish to the oyster beds in the harbor (which have recently been estimated to have been the largest in the world). The wide river on the island’s western edge—today known as the Hudson—was called Muhheakuntuck (“the river that flows two ways”), and it took on mythic overtones for the Lenape. The legend went that they had been told in a vision to journey until they found such a river and to settle there. At its mouth, as it empties into New York Harbor, the river is a tidal estuary, so affected by the ocean that significant tidal activity reaches 150 miles upriver, all the way to Troy, New York. The river remains brackish for 60 miles, to present-day Newburgh. To casual observers, the river’s odd flow is most visible in winter, when it is dotted with ice floes; as the tide goes out, the floes move slowly downstream as one might expect. But when the tide turns, the ice changes direction and begins to float lazily back upstream.

Other rivers and streams were equally important, though the ones on Manhattan have all either been obliterated or are now underground. Maiden Lane in the Financial District was once a path along a small stream named for the young Dutch women who went there to do the wash. Even today, walking through this part of town, it is easy to imagine the banks of this little river sloping downward to the vanished streambed.

Perhaps the most famous stream is in Greenwich Village. Just south of Washington Square lies tiny Minetta Lane. Intersecting it is a one-block thoroughfare, Minetta Street, and a century ago, there was also still a Minetta Court and a Minetta Place, all of them coming together to form a strange, serpentine pattern. Those streets mark the onetime course of the Minetta brook, a small stream that still runs in the storm drains below the pavement. (Some claim that Minetta is a Lenape word, but in fact it’s an English corruption of the Dutch name for the creek, mintje kill, “tiny stream.”)

Other nearby streets, like MacDougal Alley, Washington Mews, and Stuyvesant Street, likely made up a Lenape trail that served as a canoe portage so that people heading back and forth between what we now call Brooklyn and New Jersey would not have to row around the southern tip of the island. Likewise, Chinatown’s Canal Street—though built in the early 1800s [22]—was originally part of a waterway that may have allowed natives to sail straight through the island at high tide.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Note to Readers

- PART 1 The Early City: New Amsterdam, Colonial New York, the Revolutionary Era, and the Birth of the New Republic, 1608-1804

- PART 2 The Great Port, 1805-1835

- PART 3 The Growth of the Immigrant City, 18361865

- PART 4 The City in Transition, 18661897

- PART 5 “The New City Beautiful”, 18981919

- PART 6 Boom and Bust, 19201945

- PART 7 The City Since World War II, 1946Present

- PART 8 Walking Tours

- Acknowledgments

- Photograph and Illustration Credits

- About the Authors