- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

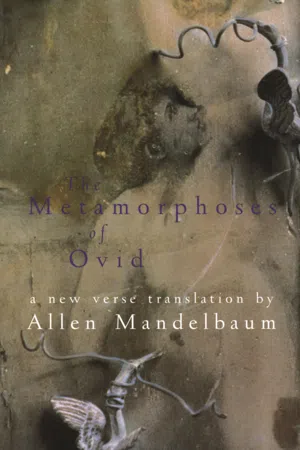

The Metamorphoses Of Ovid

About this book

Through National Book Award-winning translator Allen Mandelbaum's poetic artistry, this gloriously entertaining achievement of literature — classical myths filtered through the worldly and far from reverent sensibility of the Roman poet Ovid — is revealed anew.Savage and sophisticated, mischievious and majestic, witty and wicked, The Metamorphoses weaves together every major mythological story to display a dazzling array of miraculous changes, from the time chaos is transformed into order at the moment of creation, to the time when the soul of Julius Caeser is turned into a star and set in the heavens. In its earthiness, its psychological acuity, this classic work continues to speak over the centuries to our time. "Reading Mandelbaum's extraordinary translation, one imagines Ovid in his darkest moods with the heart of Baudelaire...Brilliant."—Booklist

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Metamorphoses Of Ovid by Ovid, Allen Mandelbaum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Ancient & Classical Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Pythagoras

Crotona had a man, Pythagoras,who had been born in Samos but then fledhis island and its rulers, for he hatedall tyranny—and so had chosen exile.Although the gods were in the distant skies,Pythagoras drew near them with his mind;what nature had denied to human sight,he saw with intellect, his mental eye.When he, with reason and tenacious care,had probed all things, he taught—to those who gatheredin silence and amazement—what he’d learnedof the beginnings of the universe,of what caused things to happen, and what istheir nature: what god is, whence come the snows,what is the origin of lightning bolts—whether it is the thundering winds or Jovethat cleave the cloudbanks—and what is the causeof earthquakes, and what laws control the courseof stars: in sum, whatever had been hid,Pythagoras revealed.

Latin [51–72]

He was the firstto speak against the use of animalsas human food, a practice he denouncedwith learned but unheeded lips. His words:

“O mortals, don’t contaminate your bodieswith food procured so sacrilegiously.For you can gather grain, and there are fruitsthat bend the branches with their weight, and grapesthat swell in clusters on the vines; there aredelicious greens that cooking makes still moreinviting, still more tender. You need notrefrain from milk, or honey sweet with scentof thyme. The earth is kind—and it providesso much abundance; you are offered feastsfor which there is no need to slaughter beasts,to shed their blood. Some animals do feedon flesh—but yet, not all of them: for sheepand cattle graze on grass. And those who needto feed on bloody food are savage beasts:fierce lions, wolves, and bears, Armeniantigers. Ah, it’s a monstrous crime indeedto stuff your innards with a living thing’sown innards, to make fat your greedy fleshby swallowing another body, lettinganother die that you may live. Amidso many things that Earth, the best of mothers,may offer, must you really choose to chewwith cruel teeth such wretched, slaughtered flesh—and mime the horrid Cyclops as you eat?Is your voracious, pampered gut appeasedby this alone: your killing living things?

“And yet that ancient age to which we gavethe golden age as name, was quite contentto take the tree-bome fruit as nourishment,and greens the ground gave freely; no one thendefiled his lips with blood. Birds beat their wings

Latin [72–99]

unmenaced in the air; and through the fields,hares wandered without fear; men did not snareunwary fish with hooks. All things were freeof traps and treachery; there was no fearof fraud; and peace was present everywhere.But someone—he is nameless—then beganto envy lions’ fare, and so he fedhis greedy guts with flesh—and sacrilegewas started. At its origins, confinedto savage beasts, the blade was justified:our iron shed the warm blood, took the lifeof animals who menaced us—and suchdefense was not a profanation—butthe need to kill them never did implythe right to feed upon them. From that seedthere grew still fouler crimes. The first to bea sacrificial victim was the pigbecause, with his broad snout, he rooted upthe planted seeds and spoiled the hoped-for crop.The goat was also prey to punishment;they butchered him on Bacchus’ altars sincehe browsed the god’s grapevines. Those goats and pigswere made to pay for what, in truth, they did;but sheep, what did you do to merit death—you, peaceful beasts, born to bring good to men,you flocks whose swollen udders bear white nectar,whose wool provides soft clothing for us—whoin life are far more useful than in death?What evil has the bullock done—that beastwho never cheats, never deceives? Helplessand innocent, he has unending patience.Ungrateful—and indeed not meritingthe grain he’s gathered—is the man who then,with harvest done, when he’s unyoked his friend,would butcher him and aim his ax againstthe neck that bears the signs of heavy tasks,the neck of one who helped him reap the crop,renewing stubborn soil. And men were not

Latin [99–127]

content with that: they even made the godsshare in iniquity: the deitieswere said to take delight in the destructionof the untiring ox. The stainless victim,unblemished and most handsome (too much beautybrings sorrow), all adorned with gilded hornsand fillets, is arrayed before the altarand, ignorant of what they mean, must hearthe prayers recited; and when they appendupon his head, between his horns, the earsof grain that he helped gather, he must standand wait and watch his executioners.When struck, he stains with his own blood the bladewhose flash he may in fact have seen reflectedin the clear waters of the temple pool.At once—while he is still alive—they pullthe vitals from the victim’s chest; and thesethey scrutinize, to see if they can readthe god’s intentions. Oh, do you, the tribeof mortals, dare to feed upon such meat?Can you lust so for that forbidden feast?Stop that disgrace, I pray: heed what I say!But if, in a...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- BOOK I

- Prologue

- The Creation

- The Four Ages

- The Giants

- Lycaon

- The Flood

- Deucalion & Pyrrha

- Python

- Apollo & Daphne

- Io & Jove

- Syrinx

- Io & Jove

- Phaethon

- BOOK II

- Phaethon

- The Heliades

- Cycnus

- Phoebus

- Callisto

- Arcas

- The Raven

- Coronis, the Raven, the Crow, Nyctimene

- Ocyrhoe

- Battus

- Mercury, Herse, Aglauros

- Europa & Jove

- BOOK III

- Cadmus

- Actaeon

- Semele

- Tiresias

- Narcissus & Echo

- Pentheus

- BOOK IV

- The Daughters of Minyas

- Pyramus & Thisbe

- Mars, Venus, Vulcan, the Sun

- Leucothoe & Clytie

- Salmacis & Hermaphroditus

- The Daughters of Minyas

- Athamas & Ino

- Cadmus & Harmonia

- Acrisius

- Perseus & Atlas

- Perseus & Andromeda

- Perseus & Medusa

- BOOK V

- Perseus & Phineus

- Proetus

- Polydectes

- Minerva, the Muses, Pegasus

- Pyreneus

- The Pierides

- Typhoeus

- Ceres & Proserpina

- Arethusa & Alpheus

- Triptolemus & Lyncus

- The Pierides—Again

- BOOK VI

- Arachne

- Niobe

- Latona & the Lycian Peasants

- Marsyas

- Pelops

- Tereus, Procne, Philomela

- Boreas & Orithyia

- BOOK VII

- Medea & Jason

- Medea & Aeson

- Medea & Pelias

- The Flight of Medea

- Theseus & Aegeus

- Minos

- Cephalus

- The Plague

- The Myrmidons

- Cephalus, Procris, Aurora

- BOOK VIII

- Scylla, Nisus, Minos

- Daedalus, the Minotaur, Theseus, Ariadne

- Daedalus & Icarus

- Daedalus & Perdix

- The Calydonian Hunt

- Althaea & Meleager

- Theseus & Achelous

- The Echinades & Perimele

- Baucis & Philemon

- Erysichthon’s Sin

- Erysichthon & Famine

- Erysichthon’s Daughter

- BOOK IX

- Achelous & Hercules

- Hercules, Deianira, Nessus

- Hercules & Deianira

- Alcmena

- Dryope

- Iolaus

- Byblis & Caunus

- Iphis & Ianthe

- BOOK X

- Orpheus & Eurydice

- Cyparissus

- Orpheus’ Prologue

- Ganymede

- Hyacinthus

- The Cerastes

- The Propoetides

- Pygmalion

- Myrrha & Cinyras

- The Birth of Adonis

- Venus & Adonis

- Atalanta & Hippomenes

- The Fate of Adonis

- BOOK XI

- Orpheus

- The Bacchantes

- Midas

- Troy

- Peleus & Thetis

- Ceyx

- Daedalion

- The Wolf

- Ceyx & Alcyone

- Aesacus

- BOOK XII

- Iphigenia

- Rumor

- Achilles & Cycnus

- Caenis/Caenus

- Lapiths & Centaurs

- Cyllarus

- Caenus

- Hercules & Periclymenus

- The Death of Achilles

- BOOK XIII

- Ajax & Achilles’ Armor

- Ulysses & Achilles’ Armor

- Ajax

- The Fall of Troy

- Polymestor & Polydorus

- Polyxena

- Polyxena & Hecuba

- Hecuba, Polydorus, Polymestor

- Aurora & Memnon

- The Voyage of Aeneas

- The Daughters of Anius

- The Daughters of Orion

- The Voyage of Aeneas

- Galatea & Acis

- Glaucus & Scylla

- BOOK XIV

- Glaucus, Circe, Scylla

- The Cercopes

- The Sibyl

- Achaemenides

- Aeolus, Ulysses, Circe

- Picus & Canens

- Diomedes

- The Apulian Shepherd

- Aeneas’ Ships

- Ardea

- Aeneas

- Vertumnus & Pomona

- Iphis & Anaxarete

- Vertumnus & Pomona

- The Fountain of Janus

- Romulus

- Hersilia

- BOOK XV

- Myscelus

- Pythagoras

- Numa

- Egeria & Hippolytus

- Tages

- Cipus

- Aesculapius

- Caesar

- Epilogue

- Afterword

- About the Author

- Connect with HMH