![]()

CHAPTER 1

REPRESENTATION

Consider the following quotation from the introduction to a book called Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation by Dalibor Vesely:

“In a conventional understanding, representation appears to be a secondary and derivative issue, associated closely with the role of the representational arts. However, a more careful consideration reveals, very often to our surprise, how critical and universal the problem of representation really is.”1

The passage goes on to develop the idea that architecture, like painting and sculpture, is a representational art. How can this be? Surely architecture is just the design of buildings, and the main function of most buildings is to provide shelter from the weather for a variety of human activities? Buildings are practical things, not so different from boats or bridges or umbrellas. How can a building represent anything in the way that, say, a portrait represents a person? What does architecture have to do with painting and sculpture? We have no difficulty with the idea that painting and sculpture are representational arts. Even an abstract painting seems to represent something, some intangible or hard-to-define aspect of experience, like an emotion or a predicament. Perhaps it is precisely because painting has no obvious practical function that we assign to it the function of representation. By the same token, architecture, because it does have an obvious practical function, ought surely to be relieved of the function of representation? So why do theorists insist that buildings often, or perhaps always, represent something beyond themselves? I have chosen ancient Greek temples to illustrate some possible answers to this question, for several reasons: because Greek temples are familiar and easy to visualize; because, being somewhat removed from our everyday experience, they have a certain simplicity and purity; and because they have so often been seen as the original prototypes of Western architecture. But this is not a chapter about Greek temples. The arguments apply in principle to all architecture.

Sculpture and architecture

One obvious way that a building can be representational is when it incorporates painting or sculpture. A very famous ancient building will serve as an excellent example. The Panathenaic frieze is a long strip of shallow relief sculpture, originally painted, that was incorporated into the temple known as the Parthenon in Athens. It is thought to represent a procession that took place annually in the ancient city on the “birthday” of the goddess Athena to whom the temple is dedicated. Most of the frieze was removed from the ruined building by Lord Elgin in the early nineteenth century and installed in the British Museum, but originally it was wrapped like a ribbon around the top of the “cella”, or enclosed part of the temple, behind the “peristyle,” or external colonnade. It was not added to the structure, like a painting hanging on a wall, but was carved in-situ out of stone of which the wall was built. It is therefore “incorporated” in the true sense. And it is certainly representational. In fact it is considered to be one of the supreme examples of representational art in the whole Western tradition. When it first arrived in London, John Flaxman, the outstanding English sculptor of the day, described it simply as “the finest work of art I have ever seen.”2

But is it architecture? Surely it is just surface ornament and not in any way essential to the function of the building. This is true, though one might argue about what the true function of the building was exactly. After all, the goddess Athena did not really need to be sheltered from the weather. Perhaps the real function of the building was precisely to provide a frame for monumental sculpture, including the long lost 32 foot nine inch high gold and ivory statue of the goddess that stood in the gloomy interior. Sculpture representing mythical scenes like the birth of Athena and her battle with Poseidon was literally framed by the gables or “pediments” at either end of the roof. Elgin removed most of this sculpture too and, looking at it close up in the museum, you can see how inventive the sculptor had to be to fit his figures into the awkward tapering space allotted to them. Evidently, the frame came before the figures. In other words, architecture took precedence over sculpture. Besides, not all Greek temples were equipped with representational friezes and pediment sculptures, so we can’t argue that these were essential components of temple architecture. We have to conclude that sculpture-framing was at best a secondary function of the building.

So far, then, architecture remains aloof from representation. But the sculpture is not the only artistic stonework in the Parthenon. More obviously “functional” parts of the building such as columns, beams, and roof overhangs are also artistically carved, though in a more abstract way. The tops or “capitals” of the columns, for example, take the form of flat plates sitting on exquisite swelling cushions of stone. In the upper part of the “entablature” that rests on the columns, relief panels called “metopes,” depicting fights between lapiths and centaurs (many also removed by Elgin), alternate with “triglyphs” embellished by abstract triangular grooves. So here representation and abstraction sit side by side. But the distinction is not as clear-cut as it seems. Most archaeologists agree that the earliest Greek temples were made of wood and that the surviving stone structures preserve certain features of the old timber technology. The triglyphs are a case in point. They probably mark the positions of the original wooden roof beams. This means they are not really abstract at all because they represent a feature of the original construction. If we accept this, then we have to see the whole building as a piece of sculpture, a representation in stone of a wooden original. And those wooden temples, houses for gods, were representations of houses for tribal chieftains, which in turn were enhanced representations of houses for ordinary people. This is not quite the same kind of representation that we see in traditional figurative painting and sculpture. The building is representing something of its own kind – another building or itself in a former existence—not something of a different kind like a human figure or a landscape. Nevertheless, we seem to have found a way in which a whole building, not just its sculptural parts, can be said to be representational.

The Parthenon, Athens—the classic threequarter view from the Propylaea, or gateway, to the Acropolis. This is perhaps the most familiar image in the whole history of architecture and is therefore an appropriate starting point. Greek temples conveniently illustrate questions of representation.

A section of the Panathenaic frieze from the Parthenon. The gods Apollo, Artemis, and Poseidon meet and converse in strikingly relaxed poses. The frieze, most of which is now in the British Museum, was carved in-situ into the upper part of the cella wall. Is it therefore an example of representation in architecture?

Triglyphs and metopes carved into the entablature of the Parthenon. The metopes represent mythical beings such as lapiths and centaurs, but the triglyphs are also representational. They stand for the ends of roof beams in the original wooden version of the temple.

Architectural history books are full of buildings that represent other buildings. We might even go so far as to say that representation in this simple sense is almost a universal characteristic of architecture. Architects in the west have for centuries copied ancient architectural details such as those we have seen in the Parthenon, and used them to ornament their own buildings. Walk down the old main street of almost any European or American city and you will see countless nineteenth- and twentieth-century versions of these details in the facades above the shop fronts. The long chain of representation—copies of copies of copies, each reinterpreting its model, sometimes altering the standard forms or combining them in new ways, sometimes returning to the pure originals—is called the classical tradition. The story of its development forms the greater part of the history of western architecture.

Columns and the human figure

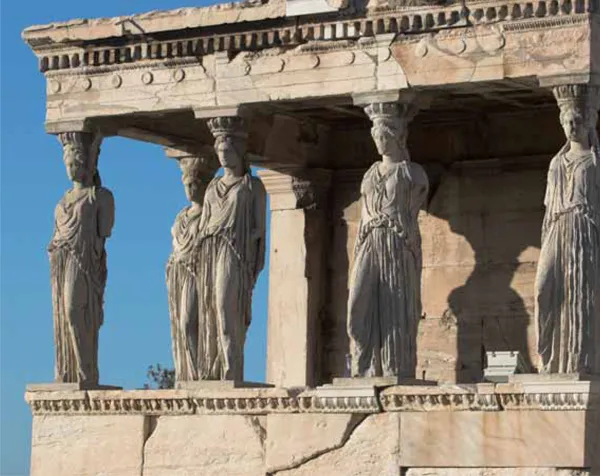

Near the Parthenon, on the high plateau of the Acropolis, stands another ancient temple known as the Erechtheion. Here we can see an even clearer example of sculpture incorporated into architecture. A kind of plinth or rostrum, sheltered by a flat canopy, projects forward from the south wall of the temple, facing the Parthenon. The canopy is supported by “caryatids”—columns in the shape of female human figures. So should we think of these columns as sculpture or architecture? They are certainly not abstract or purely functional. In his treatise De Architectura, the ancient Roman architectural theorist Marcus Vitruvius Pollio tells us that caryatids represent the women captured by the Spartans when they sacked the city of Caria and killed all the men. We shouldn’t take Vitruvius too literally. In the ancient world mythical and historical truth did not necessarily coincide and in any case the designation of these particular column figures as “caryatids” is relatively recent. In the modern, archaeological sense, the “true” origin and meaning of these figures, and of classical architectural details in general, remains obscure. It may be, for example, that the volute capitals of “Ionic” columns, like those supporting the other two porticos of the Erechtheion, are stylized representations of the horns of sacrificed rams hung up on the building like trophies. Perhaps other ornamental features, like swags and festoons, egg-and-dart moldings, acanthus leaves, and acroteria, have similar ritual origins. We don’t know for sure. They remain mysterious, which makes their survival in the modern world all the more remarkable.

The Erechtheion stands opposite the Parthenon on the Acropolis. It is an asymmetrical composition of symmetrical elements. Here the “order” is Ionic. Column capitals take the form of volutes or scrolls. But what do they represent? We do not know for sure, but their origin may lie in the horns of sacrificed rams, hung on the building like trophies.

But to return to the caryatids, whatever their origins it seems perfectly clear that in the minds of the designers of the Erechtheion there was a connection between the idea of a column and the idea of a standing human figure. Could it be that all classical columns in some sense represent standing human figures? For centuries, architects and theorists have assumed this to be the case. A refinement of the theory is that Doric columns, like those on the Parthenon, represent sturdy male figures; Ionic columns, like those on the Erechtheion, represent matronly female figures; and Corinthian columns—a relatively late Greek invention—represent slender young girls. Well, in archaeological terms, this is very questionable, but that doesn’t necessarily negate the general theory that seems in some primitive way to correspond to our inner experience. Projecting human characteristics onto inanimate objects is something we do all the time, consciously or unconsciously. We see giants in the clouds, grasping hands in the branches of trees, faces in the fronts of houses—and standing figures in classical columns. The function of a column is to bear load, and we seem to feel the weight of that load, empathizing with the column as if it were a character in a drama. The caryatids are an artistic expression of a psychological truth. So classical columns represent human figures. This is a kind of representation we have not encountered so far. It is neither pictorial, like the Panathenaic frieze, nor reproductive, like the classical tradition, but symbolic, in a subtle and rather profound way. The broader idea now is that buildings can represent aspects of human experience. Standing upright and carrying a load may not seem a particularly important experience, but in its commonplace nature lies its strength. It is something the whole of humanity understands and shares.

The caryatids of the Erechtheion are clearly both structural columns and representations of people. Is there a sense in which otherwise abstract structural columns can be said to represent standing figures?

Sometimes it is necessary to study the commonplace and restate the obvious in order to understand the most basic truths. For a figure to stand upright, there must be something to stand on—a ground; the ground—the surface of a planet exerting a gravitational pull on the figure itself and on the load it carries. There is a limit to the load that can be carried, a limit set by the characteristics of the human body and of the planet that it inhabits. If there is a ground, there must also be a sky, and between them a dividing line, the horizon. Body and planet are in perfect harmony. How could they be otherwise? The body evolved on the planet, adjusting itself over millions of years to these particular conditions. The planet in a sense gave birth to the body. They are inseparable. We experience the presence of ground and sky not just when we look out over a landscape but in every moment of our lives. The experience is so fundamentally human that we take it for granted and never talk about it. But perhaps we should. Perhaps we are missing the truth that lurks in the blindingly obvious. Now that we can fly in the air and travel to the Moon, more than ever we need to remind ourselves that ground and sky are not just phenomena that we observe from an objective, scientific standpoint, but are a part of our very nature, locked into the form and substance of our bodies. It was ground and sky, horizon and gravity, horizontal and vertical that made us what we are, that made us able to stand upright and bear a load. So when we say that a classical column—or any column—represents a standing human figure, we are not saying anything trivial. We have hit upon something fundamental in the nature of architecture.

Regularity in architecture

Are there perhaps other ways in which architecture is symbolic of what we cannot avoid calling “the human condition?” Yes, there are. Regularity is a quality that we normally associate with architecture. When we use architecture as a metaphor, when, for example, we talk about the “architecture” of a novel, we are talking about ordered structure, the hidden regularities that hold the novel together and make it a coherent work of art. Looking again at the Parthenon, we note that its columns are identical and regularly spaced, that its double-pitched roof is symmetrical, and that its corners are right angles. Actually, as any student of ancient Greek architecture knows, part of that last sentence is not strictly true. The designers of the Parthenon have made some subtle adjustments to what would otherwise be a strict mathematical regularity. They have, for example, pushed the corner columns in slightly. You don’t notice it at first, but when you do you realize that it is actually quite a big adjustment. The fact that you didn’t notice it is important. One theory about this adjustment is that it corrects an optical illusion. If the columns were all evenly spaced, so the theory goes, then the corner columns would look as if they had been pushed out slightly. In other words, the row of columns would look irregular. So these adjustments, though they introduce a mathematical irregularity, only serve to show how important apparent regularity was to the ancient Greek architects.

There are different kinds and degrees of architectural regularity. Symmetry is a kind of regularity. A circular, domed building might be considered more symmetrical than a building like the Parthenon, which displays “bilateral” rather than “axial” symmetry. Bilateral symmetry is by far the most common kind in architecture. Is it perhaps in some way representational? Human bodies are, outwardly at least, bilaterally symmetrical, and this symmetry is not just observed from the outside but experienced from the inside. It affects the way we see the world, encouraging us to divide it into binary opposites—left and right, black and white, good and bad, yin and yang, on the one hand this, on the other hand that. So although a Greek temple looks nothing like a human body, nevertheless it shares with it this fundamental quality. It might be said to represent, at some level of consciousness, this aspect of human experience. Architectural symmetry is not always simple and unified as it is in the Parthenon. The symmetry of the Erechtheion, for example, is fragmented and complex. The component parts of the building—the rostrum, the north portico, and the main body of the...