- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Research Methods for Architecture

About this book

While fundamentally a design discipline, architectural education requires an element of history and theory, grouped under the term 'research'. However, many students struggle with this part of their course. This practical handbook provides the necessary grounding in this subject, addressing essential questions about what research in architecture can be.

The first part of the book is a general guide to the fundamentals of how to do research, from assembling a literature review to conducting an interview. The second section presents a selection of case studies dealing with such topics as environmental psychology, the politics of space, ethnographic research and mapping.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Scottish Parliament Building and gardens.

Chapter 1:

Defining your research question

The research question – ‘What do you want to find out?’ – is both a crucial starting point for your research and an ongoing process of refinement.

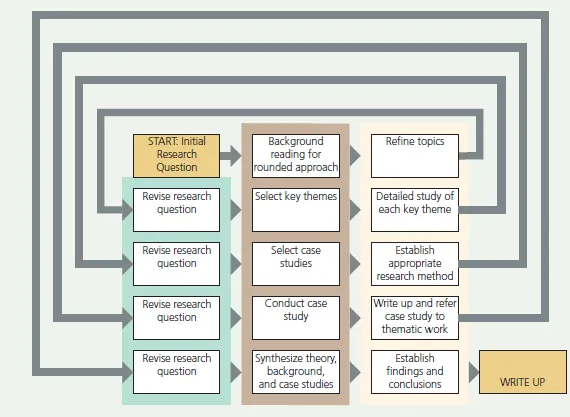

Far from being a fixed title, you will typically revise your research question continually as your project develops. Research is not a simple progression from A to B to C, rather it proceeds as a series of parallel activities, looping back to revisit ideas.

What do you want to find out?

There are a number of ways of diagramming your research process. Popular approaches include the use of Gantt charts and mind mapping. While Gantt charts allow you to programme time spent on tasks in a relatively rational manner, they often fall foul of presumptions regarding the length of time some research tasks take, and the realities of thinking through a complex problem. Mental mapping, while popular in terms of generating clouds of relations and terms, can serve to disorganize thoughts rather than give them structure. Care needs to be taken with the manner of diagramming, as it reflects the structure underlying your research process.

The overall forward trajectory remains important, however, in structuring your research practice and, just as importantly, in how a reader will approach your work. A research question can be a specialized kind of title, and often fulfils this role within the text. This approach allows you to define your research as a practice, an ongoing enquiry led by your curiosity about an architectural issue. Your question might reference a specific theoretical framework, a kind of methodology, current developments in the field or some other reference point to give the reader a clue as to your own chosen context, theoretical framework and methodology.

Alternative diagrams for establishing your research question. This diagram shows academic research as a series of loops.

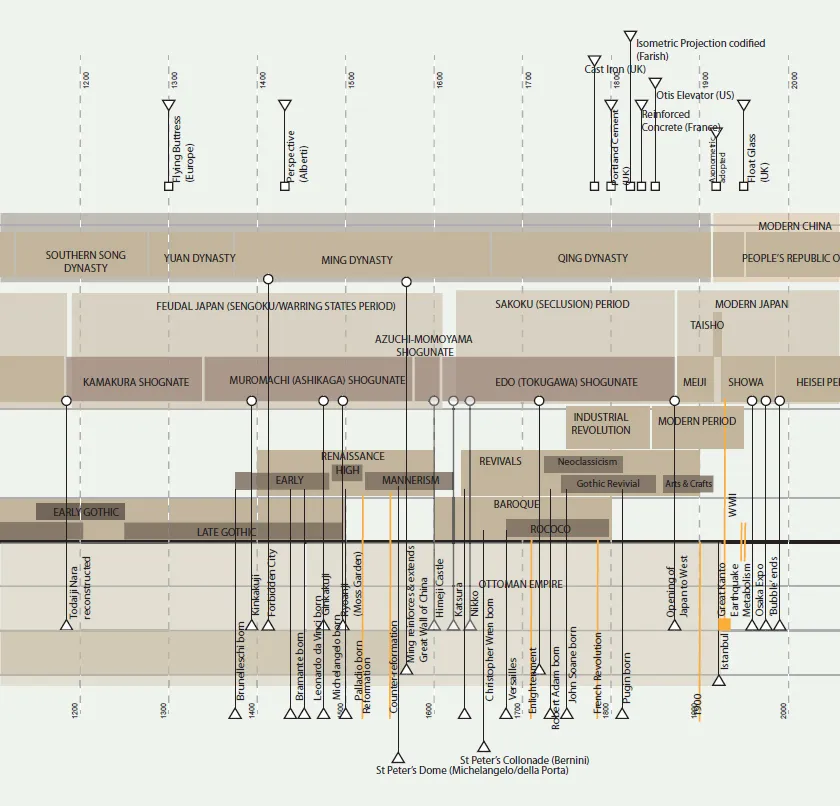

Using a simple diagram such as a timeline can throw up interesting relationships and correspondences between developments in different parts of the world. For example, noting that a building such as Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, Japan, dates from the same period as the Italian Renaissance can form a starting point.

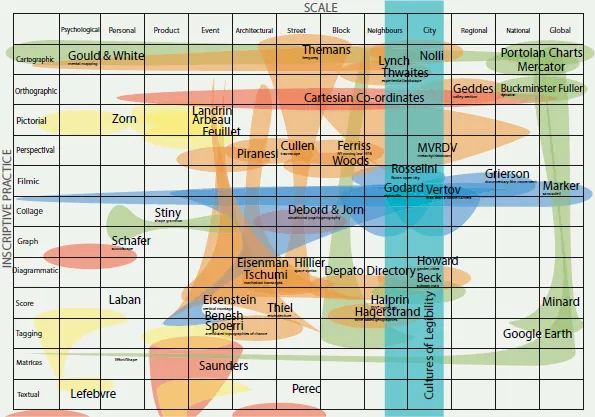

Mapping against axes such as this diagram of alternative diagramming and notation practices in architecture can begin to identify common historical themes in representational strategies.

The research question can be used in a number of ways. When publishing in academic and professional journals or proposing a conference paper, you might be asked to provide a short abstract of the research you are presenting. This abstract is a précis or summary of the research, focusing on the primary research question. This is more substantial than a summary, and focuses on what is unique about your work. The abstract is often used to print proceedings for larger conferences with parallel sessions, or at the head of a journal article, and is the audience’s introduction to your work.

Writing an abstract requires discipline, since you have a very limited number of words to provide a full account of your research, and the aspect of it that you intend to present in your paper. It can indicate a larger project, showing that this has a broader appeal, but needs to convey the main points of your work:

Context: Where or when you are studying. The work of a particular architect or group of architects, or a specific methodology or technology can all be considered as the context of your work. Is the work a case study or a survey of a broader collection of works?

Theoretical framework: Which theories and writers have helped you to articulate your work? This can include theories you have taken issue with as well as those you agree with.

Methodology: How have you conducted the research? Fieldwork, interviews, statistical analysis? All are valid approaches, but outlining this from the start tells your reader a lot about what to expect in the end. Each of these is dealt with elsewhere in this book, but it is important to learn to make your abstract both concise and accurate. As a student, you will most often be asked to produce this kind of writing as a more formal essay plan, in which case you should cover the following in addition to the above:

Structure: Break this down into the chapters and subheadings, with a paragraph for each, describing what you intend to say. Remembering the pattern of introduction, development and conclusion within each section of this is worthwhile; good essays often have this structure present at the macro, meso and micro scales.

Key texts: Slightly elaborated from the theoretical framework above, an essay plan requires you to give an indication of the bibliography you will draw upon, and for what purposes. Some texts are critical and theoretical, but others provide you with information and broad context. Each of these should be detailed here, stating which texts will be used for which purposes.

In practical terms, your research question has several versions – in the introduction and in the conclusion to a written work, and perhaps in some form in the title, even if this is implicit rather than presented as an actual question marked with a question mark. What is crucial is that your title gives some indication of the aims of the work. A fuller exploration of your research question should form part of the introduction. This allows you the space to develop the depth of your enquiry, exploring some of the implications and also explaining why you have chosen this approach instead of others that might also appear possible, or even obvious. Your job is to defend the piece of work you have embarked upon.

In examining a historical context, the work of an architectural firm, or the social networks activating a space, it is important to have clarity regarding what you would like to find out. Even when writing about your own design process and presenting it as practice-based research (see Chapters 14 and 15), you are challenged in writing a research question to say what your architecture is about. What is your agenda for the built environment and how are we expected to interpret your work?

From the outset, before you begin to find sources and assemble your findings, it is important to let your curiosity about the topic inform your research. Without this, your work will be an empty exercise lacking in interest, and simply displaying an ability to present the available data on a given topic. If you are clear about your aims, then you will have more control over the reception of your work. It is more likely to be assessed on the terms you set out, allowing you to determine the terms of the debate to some extent.

Defining your terms

Your question should include the terms of your engagement with the material, the context and the works of architecture in question. It is important, usually in your introduction, to ‘unpack’ the terminology you intend to use. In considering a word as a container of ideas, it is conceptually helpful to open this out, and, in an orderly manner, lay out the various constituent parts of the term, what its implications are, and how you intend to use it. Certain words might seem, at first glance, to be obvious and clear, but even the simplest language can be used in very specific ways.

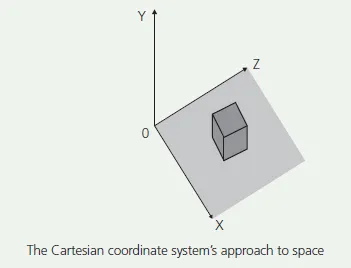

An example relevant to architecture might be the use of the word ‘space’: Space as geometry: The Cartesian coordinate system defines space according to three dimensions of X, Y and Z. This is an abstract definition of space, where every point in space has the same qualities as every other. This has its uses, but can also be problematic when discussing the experiential qualities of space.

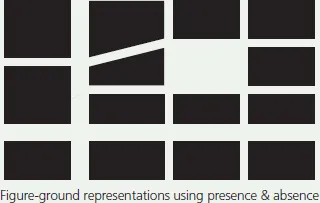

Space as absence: Space can be understood as a negative quality, a lack of substance, bounded by walls, floor, ceiling or defined by some other kind of boundary. This has some implications for our representations of space and the ways in which architecture thinks about positive and negative space as a discipline.

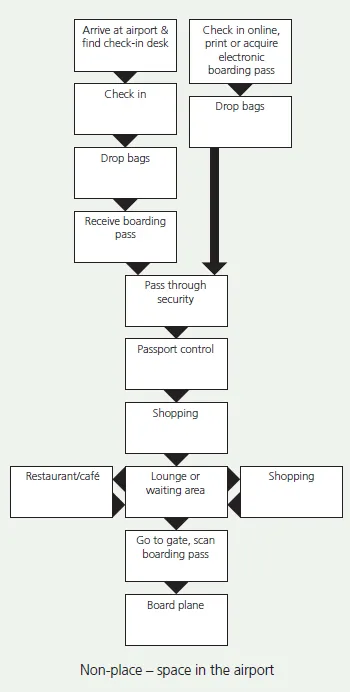

Space as a container for activity: Space is where things happen. Often in the literature, the geometric abstraction of pure space is contrasted with place, where people have taken possession of a territory by virtue of their actions there. Defining terms in oppositions is one way to make your definition clearer, but does require you to establish a taxonomy or categorization. This systematization of your description can work like a map, giving potential new qualities, as Marc Augé identifies in his influential text Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity1. In this text, Augé presents spaces that resist place-making, or that remain indeterminate deliberately.

The conventional coordinates of mathematical space.

A figure-ground diagram that uses concepts of positive and negative space.

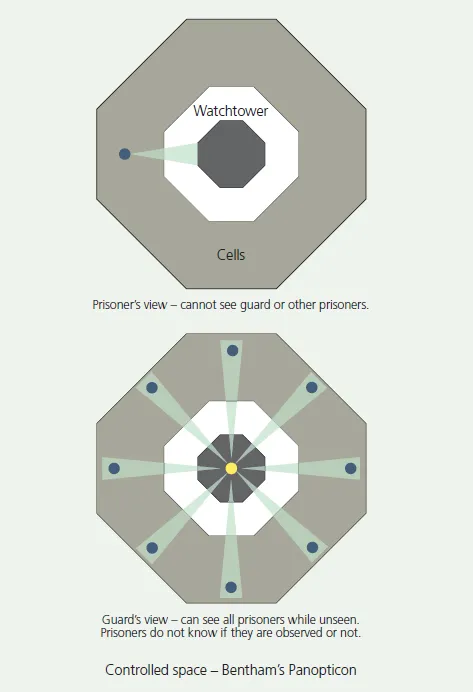

Space as socially produced: Philosophers and critical theorists including Henri Lefebvre and Michel Foucault investigate the idea that qualities of space are not so much physically determined as socially determined2. The same volume may be enclosed by a cathedral or a concert hall, but the activities that take place within each are substantially different.

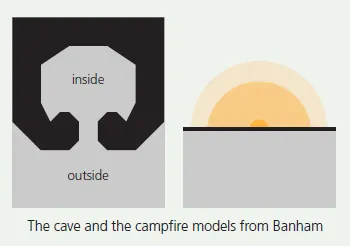

The cave and the campfire: Architectural writer Reyner Banham presents two alternative discussions of space in his text The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment3. The cave is the bounded model of space, where a perimeter is clear and present, whereas the fire gives a relational, graduated notion of space as distance from a particular point and the implications of this.

The model of the airport as a space that resists inhabitation.

Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon as a model of space that produces behavioural effects.

Banham’s notion of the cave and the campfire as spatial models.

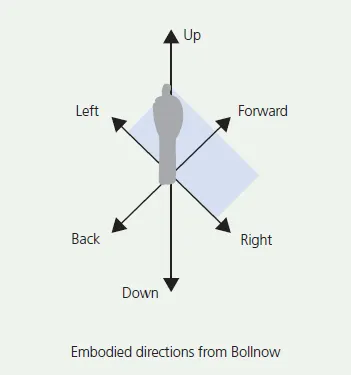

Space and temporality: Often, the terms of space and time are opposed to one another, but they do not behave like a dichotomy: they are opposites, but in the sense of complementary ideas that operate in completely different ways. Otto Bollnow gives a particularly powerful account of this in his text Human Space, where the experiential is wrested from temporality and applied once again to our concept of space.4 Indeed, many writers, including anthropologist Tim Ingold, argue that we cannot conceptualize human life out of context. It must be considered in an environment, since space is essential to being.5

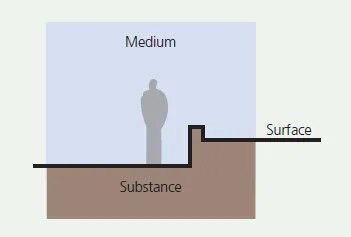

Medium as an alternative to space: Other fundamental ideas of space come with the work of environmental psychologist James Gibson in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception.6 Gibson’s model understands space as a medium, with varying viscosity and thickness, surfaces that mediate between one condition and another, and substances that are those hardened areas that remain impermeable. This model offers some frustrations to designers, but also helps them to consider atmospheres and materiality in novel ways.

We can see here that there are multiple ways to understand such a fundamental word as ‘space’, and that these definitions are sometimes mutually exclusive. Further elaboration in this case can be found in the work of Edward Casey, who conducted a comprehensive study of the concept in The Fate of Place, Getting Back into Place and Representing Place.7 In some cases, the word is defined in opposition to another term, such as ‘place’, while it can also be given shape by attaching it to another concept such as ‘geometric’ or ‘anthropological’. Given this multiplicity, it is therefore good academic practice to explain what your take is on the key terms of your study, for example by defining a period of history. Questions you may consider might be: What is the extent of the Renaissance? What are the limits of a geographically based study of London? How do you define sustainability?

In cases of real contention, one strategy is to actively exploit the tensions present within different definitions. This allows you to understand the flexibility possible within a word or concept so that it becomes a useful tool for thinking with.

Space oriented by the human body in terms of up, down, left, right, forward and back.

Gibson’s triad of Medium, Surface and Substance.

Framing a research question

Research often begins with a question. While this is a simple idea, it offers a great deal of flexibility to the researcher and expresses the fundamental character of the activity as grounded in a spirit of curiosity – what is it that you would like to find out in the first place?

The research question is different from an everyday query in a number of ways, of course, and must indicate several things about your research. It is worth remembering at this stage that it might not always come first, and that formulating a good research question is a process that you will benefit from taking some time over. Broadly speaking, questions can belong to a number of different categories:

The given question

You might be working to an assignment, and be given a question to respond to. This can often be seen as limiting, but it is also an opportunity as it takes many of the decisions out of your hands and allows you to focus on providing an answer that is well worked out and innovative. There are as many ‘answers’ to a research question as there are researchers, even given precisely the same resources.

While a given question might be a substitute for your own research agenda in some cases, it is best practice to make the question your own, and to explore this further ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction: What is architectural research?

- Part 1: Fundamentals of Architectural Research

- Part 2: Practical Applications and Case Studies

- Glossary

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgments

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Research Methods for Architecture by Ray Lucas,Raymond Lucas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.