![]()

1

Cults or Subcultures?

Reckoning with Collective Creation in the English Pop World

Thomas Crow

You poor old prehistoric monster, … I do not reject the working classes, and I do not belong to the upper classes, for one and the same simple reason, namely, that neither of them interests me in the slightest, never have done, never will do. Do try to understand that, clobbo! I’m just not interested in the whole class crap that seems to needle you and all the tax-payers—needle you all, whichever side of the tracks you live on, or suppose you do.1

This imaginary diatribe comes from the first-person narrator of Absolute Beginners, the 1959 London novel by Colin MacInnes (figure 1.1). Never given a name, this 16-year-old school-leaver, style merchant, connoisseur of the popular, and freelance photographer, plies the London streets on an Italian scooter in pursuit of both his next gig and his beloved but elusive Suzette. MacInnes, then 45, created an enduring prototype for the postwar London teenager, one who leads the reader on a tour from one hip circle to the next, concluding with a Dante-esque descent into the 1958 riots in Notting Dale (the narrator’s beloved “Napoli”), when African and Caribbean migrants (the narrator’s allies) are set upon by gangs of White nationalist thugs. Writing in 1962, the philosopher Richard Wollheim, friend and admirer of the novelist, describes this character, along with the restless youthful cohort he represents, as having “rejected the conception of the city as a solid three-dimensional environment that shapes and enfolds his life, and instead regards it as a kind of highly coloured backcloth against which he acts out, and upon which he projects his fantasies.”2

Wollheim capitalizes Teenager to name the type, but the word in actual use for such a protagonist was Modernist. Most often shortened to just Mod, the word signified a young man, sharply dressed in a narrow, Italian-style suit, mobile and independent on a likewise Italian Vespa or Lambretta, alert and energized on a Dexedrine high. The funds to support this mode of life most often came from some entry-level service occupation, plentiful in the years of post-war expansion, which permitted the young male products of working-class terraces to escape into this self-invented metropolitan whirl. Their emergence followed the intellectual revaluation of Americanized consumer products by the artists and writers of the Independent Group, whose enthusiasms they appeared to be aligning with an organic class orientation. At the same time, the renowned class of 1959 at the Royal College of Art—David Hockney, Derek Boshier, and Peter Philips among them—included Pop practitioners of the same age cohort as the prototypical Mod.

Figure 1.1 Colin MacInnes, Absolute Beginners (New York: Macmillan, 1960), first US edition. Cover photographer: James Noble. Photograph courtesy of Thomas Crow.

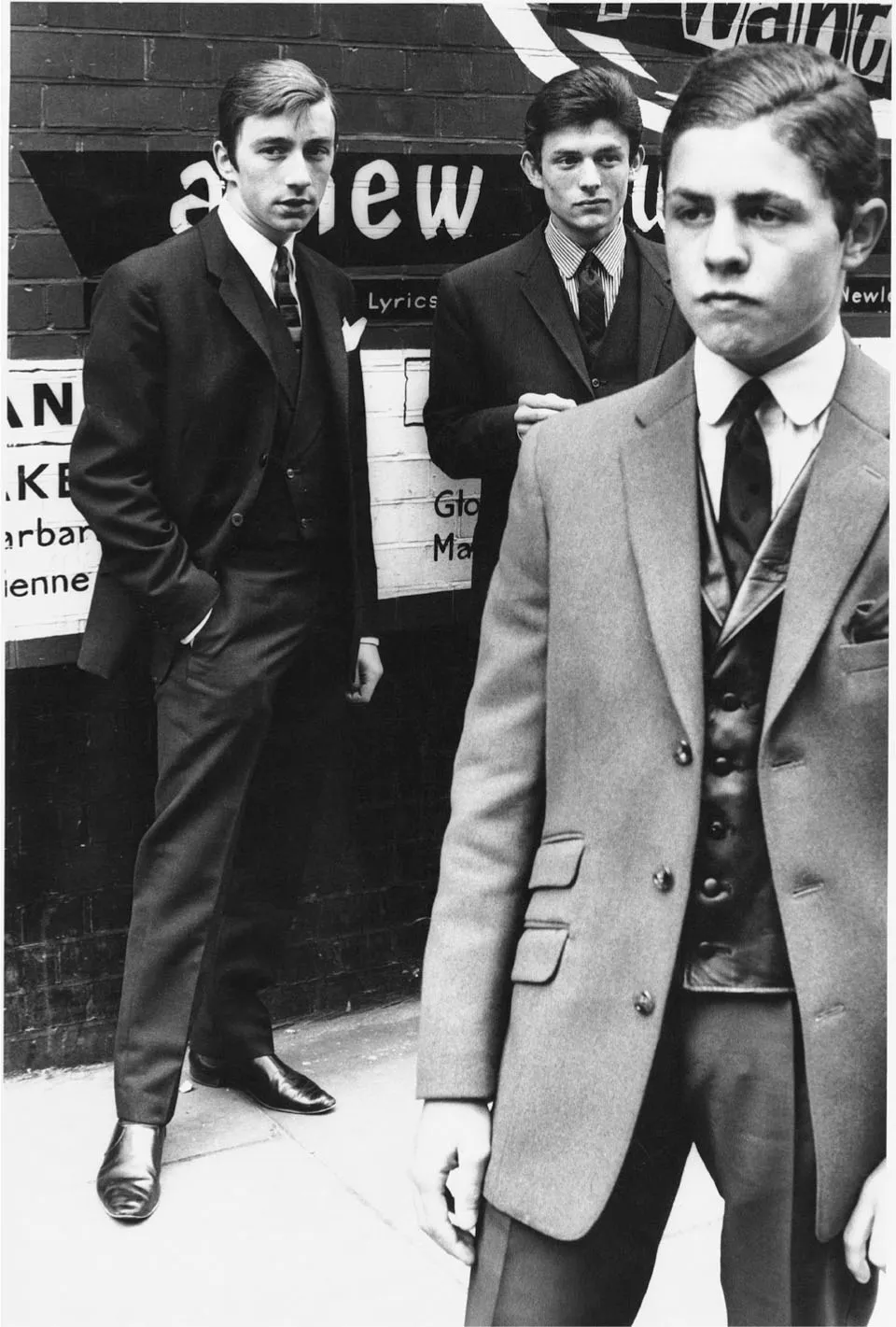

Figure 1.2 Don McCullin, Young Mods, London, 1962 (Miki Simmonds, Peter Sugar, Mark Feld). © Don McCullin/Contact Press Images.

By the year of their graduation in 1962, the esoteric sensibility captured by Absolute Beginners began to emerge in the mass media. Ambitious publisher (and future Tory grandee) Michael Heseltine launched Town magazine as a flashy barometer of current London culture. In an early issue, he dispatched a journalist alongside no less a photographer than Don McCullin (fresh from covering the 1961 Berlin crisis) to document the underground notoriety of three top Mods in Northeast London.3 McCullin’s moody shot of the trio (figure 1.2) exposes the leather waistcoat of their tacit leader Mark Feld, the pride of his cultivated wardrobe, while inserting the young Mod style firmly in the downbeat London landscape to which the TV films of Ken Loach would shortly afterwards lay claim. Feld (later to transform himself into the Glamrock luminary Mark Bolan) delivered one quotation that has disproportionally colored the image of the Modernist ever since: asked about the still-reigning Conservative Party, he replied, “They’re for the rich, so I’m for them.”

The fact that Feld likewise extolled the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament has not weighed in the balance, perhaps because he cited its “exhibitionist” character as the reason for his approbation. His Tory quip has anecdotally reinforced the condescending sociological scrutiny of the Mod phenomenon. It has become a common reading of the working-class Mod preoccupation with stylish suiting to see it as aspirational imitation of the English professional classes by school leavers trapped in dead-end clerical or service jobs. One influential formulation characterizes the Mod style “as an attempt to realize, but in an imaginary relation, the conditions of existence of the socially mobile white-collar worker.”4 From this orthodox Marxian outlook, the outburst scripted by MacInnes for his protagonist would readily be dismissed as classic false consciousness. But that persistent framework (to be examined further below) remains trapped in one-to-one mimetic correspondence of Modernist dress codes to an English stereotype of middle-class respectability. The Modernist templates were trans-Atlantic and trans-racial before anything else, as its deep emotional urgency came from music, from bebop, cool jazz, and the more propulsive hard bop that gained wider popularity among black audiences toward the end of the decade. Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan, the Californian stars of the cool tendency, fostered an imported Ivy League look. Photographs of Baker and Mulligan, as put together as two outlandishly talented young heroin addicts could possibly present themselves, spoke to the coded secret of an outwardly ultra-conformist appearance: two literal outlaws refusing outward markers of marginality.

Both musicians enjoyed the added disguise of white skin, their addictions in part an elective solidarity with their black peers who were marginal in the larger society in ways that superior abilities could never entirely overcome. Miles Davis (figure 1.3) was renowned for this, “cool” both in his clear, measured playing and in the understated elegance he cultivated in his dress, inward rage contained by playing down rather than acting out. Mod chronicler Paolo Hewitt puts it well: “By dressing in the clothing of those who fiercely resent their culture, their music, the color of their skin, Miles and his peers are playing the enemy beautifully, walking amongst them while changing the landscape forever. You think he’s a bank manager, in fact Miles is a revolutionary in silk and mohair.”5

Figure 1.3 Miles Davis, 1960. A.F. Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

All of this was understood in London and emulated by self-conscious, minority devotees of modern jazz as a wordless form of defiance against the subservience expected of Secondary-Modern products. What the Mods knew, in their discerning fandom, was that a fine suit on an American jazz musician escaped such literal-minded reading of class signifiers. A top Mod was not putting on a disguise as middle class; he understood a certain kind of suit as already a disguise. At the beginning, no more than a few hundred fans in the most discerning clubs opted for t...